Colombia’s security forces will be cracking down on dissident elements of the FARC and occupying territories abandoned by demobilized guerrillas, but doubts remain as to whether they have the capacity to carry out such a monumental task.

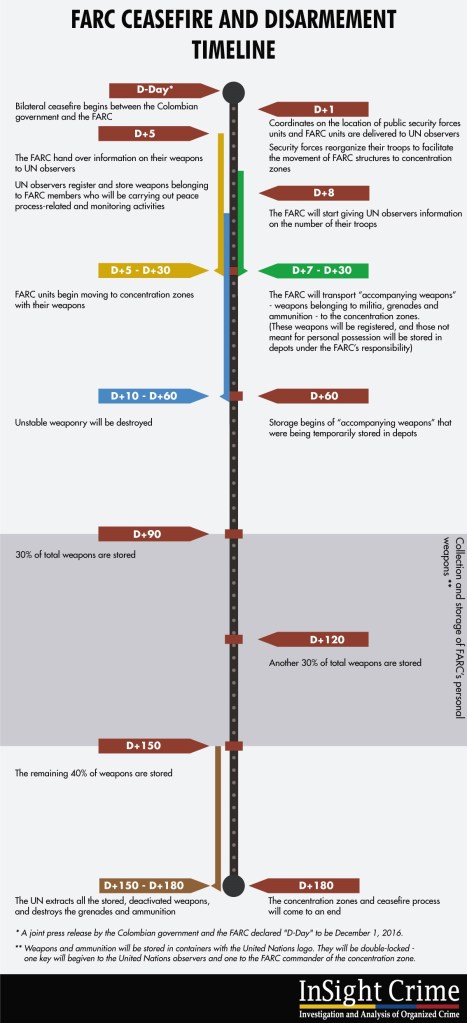

Colombian Armed Forces Commander-in-Chief Gen. Juan Pablo Rodríguez has announced that the army, navy, air force and police will soon begin occupying areas historically controlled by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC), as they move towards concentration zones where they will hand over their weapons and prepare to enter civil society. (See timeline below)

The so-called “Plan Victory” will be initiated on January 1, 2017, and “will seek to establish institutional control in these territories not only through the presence of the armed forces and police, but through all state bodies,” Gen. Rodríguez said. “In this way, we will stop other violent [armed groups] from occupying these spaces.”

SEE ALSO: Coverage of FARC Peace

Around 15,000 members of the armed forces will reportedly be deployed to communities located around the FARC’s concentration zones.

The Colombian general also stated that authorities will fight members of the FARC guerrilla group who refuse to adhere to the peace process, El Colombiano reported.

“The FARC will receive the full force of military and police operations,” Gen. Rodríguez stated, specifying that around 190 dissident rebels had been identified.

Last week, Defense Minister Luis Carlos Villegas ordered a military offensive against FARC dissidents after the guerrilla organization expelled five commanders from their ranks, apparently due to their links to criminal activities.

Information accessed by El Colombiano states that FARC units have deserted or abandoned the peace process in the departments of Nariño (the Daniel Aldana Mobile Column/Front), Guajira (19th Front) and Vaupés (1st Front). In addition, the five commanders who were expelled last week were leading members of the FARC’s 7th, 16th, 40th, 43rd, and 62nd Fronts in eastern Colombia. At the time, certain reports suggested that up to 300 FARC members had deserted the demobilization process.

Other units at imminent risk of desertion include the 57th Front in Chocó and the 32nd in Putumayo, according to the news outlet.

InSight Crime Analysis

There will be two main issues for the armed forces as they move into former FARC territories in order to prevent a vacuum from opening up that could be filled by other criminal actors.

First, the fragile ceasefire between state forces and the FARC will come under even more pressure. Even though authorities will only be targeting dissident rebels, it will probably be a challenge for them to make this distinction. Indeed, a case of mistaken identity allegedly led to the killing of two FARC members in Bolívar department in November, with security agents claiming they believed the insurgents to be members of the ELN.

Furthermore, FARC members who are still moving towards concentration zones, or who do not remain in these areas, may be at risk. This danger should be mitigated if the FARC adhere to the established timeline for demobilization. Both the FARC and government announced that the “D-Day” — which marked the start of the guerrillas’ demobilization process — commenced on December 1, meaning that all rebels should be gathered by December 31. The FARC leadership has since confirmed that its troops are moving to the designated zones.

SEE ALSO: FARC News and Profile

Nevertheless, up to 600 FARC members in Putumayo department have been refusing to move to their concentration areas due to the threat posed by local “paramilitary” groups, suggesting many could by left exposed once the deadline passes.

Furthermore, the state will be struggling to obtain the resources needed to occupy former FARC territories. To be sure, the Ministry of Defense’s budget will increase by around 2 percent in 2017, and Colombia is expecting hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of international “post-conflict” aid. However, recent state attempts to establish control in areas that have long been abandoned by the government have been insufficient, and there are concerns of a shortfall in international funding.