The case of Mexico’s 43 missing students remains unsolved after two years, underscoring the reasons for the deep distrust many Mexican citizens harbor toward their government when it comes to matters of crime and security.

On the evening of September 26, 2014, police in the city of Iguala in Guerrero state attacked a group of students from a teacher’s college in the nearby town of Ayotzinapa. Over the course of a few hours, the police — along with several unidentified gunmen — killed six people, injured dozens more, destroyed several vehicles and apprehended 43 students, none of whom have been seen alive since that night. (See InSight Crime’s timeline of the case below)

The Mexican government’s official investigation concluded in January 2015 that the police had handed the students over to a local criminal group known as the Guerreros Unidos, who had mistaken them for members of a rival gang. The alleged leader of the Guerreros Unidos, Felipe Rodríguez Salgado, alias “El Terco” or “El Cepillo,” testified that he ordered the students to be killed and their bodies burned at a trash dump in the nearby town of Cocula.

But subsequent investigations by independent experts have refuted this version of the story. Government witnesses provided inconsistent testimony — some were tortured — and forensic evidence contradicted the claim that the students remains were incinerated at the trash dump.

Two years since the students’ disappearence, many questions about what happened that night remain unanswered. One of the main mysteries revolves around the impetus for the attack. Though the government has claimed the students’ killing was a case of mistaken identity, a theory put forth by independent investigators suggests local security forces may have been attempting to protect a shipment of drugs hidden on a bus the students had commandeered.

Another major unresolved question involves the role of the Mexican military in the students’ disappearance. In a recently published book, reporters Francisco Cruz, Félix Santana and Miguel Ángel Alvarado uncovered evidence of suspicious calls to a cell phone belonging to one of the students — Julio César Mondragón Fontes, who was found dead and mutilated the day after the attack. Mondragón’s phone reportedly recieved incoming calls for months after his killing, some of which placed the device near a military base in Iguala and near the headquarters of Mexico’s civilian intelligence agency, known as CISEN.

Inexplicably, the phone and its call logs were not among the evidence the government turned over to an independent group of experts tasked with providing support in the case. It is unclear why the government did not provide this seemingly crucial evidence, but Cruz has alleged the existence of a “conspiracy of silence to protect the armed forces,” which he described as “untouchable in this country.”

In July, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) announced that it will name at least two special advisors to monitor the government’s investigation of the case going forward.

InSight Crime Analysis

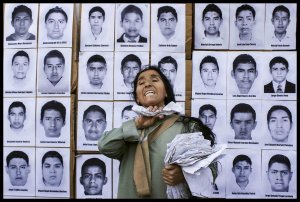

Mexican security forces have been accused of grave human rights abuses in several other instances in recent years. But few of these cases have had the same impact as the disappearance of the students from Ayotzinapa. News of the events at Iguala sparked outrage across Mexico, with many protesters laying the blame squarely on the government — as evidenced by the common refrain “fue el estado” (“it was the state.”)

Recent public opinion surveys have shown that few Mexicans feel safe in their communities, and even fewer trust their local police forces. The Iguala case contributed significantly to the erosion of public trust in the authorities. This has been compounded by several factors including continuing indications of corruption among security forces, a general lack of accountability for security force abuses, persistently high levels of violence, and the apparent inability or unwillingness of the government to make serious efforts to determine the whereabouts of the thousands of people reported missing in the country. In fact, only two of the 43 missing students from Ayotzinapa have been found to date — both of them dead.

SEE ALSO: Mexico News and Profiles

Given all this, it is rather unsurprising that Mexican citizens display little confidence in the authorities that are supposed to ensure their security. The Mexican government’s failure to bring closure to the families of the victims of the incident at Iguala underscores this dynamic. And with crime rates rising in many parts of the country, security officials should be mindful of the consequences of this lack of trust. In parts of Mexico facing severe security crises like Guerrero and neighboring Michoacán, citizens have taken matters into their own hands, in some cases exacerbating already complex security problems and creating difficult dilemmas for local authorities.