The collapse of a criminal case against the former mayor of Cancun adds another embarrassment to a string of failed attempts by Mexico‘s authorities to charge politicians allegedly linked to organized crime.

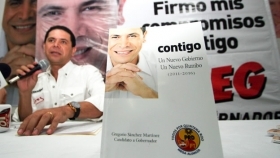

Gregorio Sanchez was released from government custody in Mexico City after officials determined that there was not enough evidence to link him to the Sinaloa Cartel, for whom he had been accused of laundering money. However, he was fitted with a monitoring bracelet and ordered to remain in the city while authorities investigated charges of human trafficking.

This was the second release in recent days for Sanchez; after more than a year in prison in Nayarit on charges that he protected the Zetas in Cancun, he was released last week after a judge found no evidence of wrongdoing. Upon his release, Sanchez was rearrested while investigators dug into the accusations of links with Sinaloa, the Zetas’ longtime enemies.

The former mayor of Cancun and member of the opposition Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) was originally arrested in May 2010, while campaigning to be governor of Quintana Roo. Although he was more than 20 points down in most polls, many accused of Calderon’s government of using the fight against organized crime to tilt the political playing field. Such accusations have grown more frequent as administration officials have responded to his exoneration on one charge by seeking to implicate Sanchez on another.

Two of the other recent attempts to strike blows against political support for organized crime also failed miserably. The arrest of Jorge Hank Rhon, the former mayor of Tijuana and scion of one of the most prominent political families, fell apart within weeks after it was revealed that the army manipulated the evidence against Hank.

The Hank debacle followed the 2009 arrest of dozens of state and local officials in Calderon’s home state of Michoacan, in an episode dubbed the “michoacanazo.” Eventually, after languishing in prison awaiting trials for years in some cases, every one of the accused was released, and the charges dismissed.

Political adversaries of Calderon have pointed to the incidents as evidence that the government has politicized public security in Mexico — Hank is a member of the opposition Institutional Party of the Revolution (PRI). However, while a majority of the Michoacan arrestees were also opposition politicians, some were also members of Calderon’s National Action Party (PAN).

If the arrest was an attempt at political point scoring, it backfired. Calderon’s government came out looking far worse after each episode, and in the case of Hank, whose links to organized crime have long been rumored, the failed prosecution seems to have given a boost to his political ambitions. Thriving on the extra attention, and the rare chance to play the victim, Hank has mused about the possibility of another run for the governor’s post in Baja California, which he almost won in 2007.

The inability to punish political sponsors of organized crime from every party has been a persistent shortcoming of Mexico’s anti-crime efforts. While dirty police are often arrested by the dozen, and even the capos have lost much of their erstwhile invincibility, the successful prosecution of a political patron is rare indeed.

Calderon has said that the main problem is corrupt judges, and has even claimed that he knows how much judges are paid to ignore the evidence against bent politicians. However, even if Calderon’s accusations have weight (they sparked vigorous denials from members of the judicial branch), at least some of the problem, as the Hank case shows, is due to Mexican police and prosecutor’s inability to build a proper case.

The inability to convict suspects is not limited to political cases. As InSight Crime noted in April, the Mexican Justice Department’s own figures show that just 28 percent of all federal arrests in 2010 resulted in a trial, to say nothing of a conviction. In the remainder, the cases were dismissed because of procedural errors or a lack of evidence.

Quintana Roo has a long history of links to organized crime. A relatively short flight across the Caribbean from Colombia, the state was the home to much of the Juarez Cartel’s organization in the 1990s, and in recent years has been controlled by the Zetas. The former governor of Quintana Roo, Mario Villanueva, served time in Mexico for protecting drug traffickers, and was later extradited to the U.S.