Prosecutors in El Salvador have charged high-ranking politicians with electoral fraud in connection to their controversial negotiations with gang leaders, opening a Pandora’s Box for public officials — long unable to deal with violent street gangs that control large swaths of the country.

While presidents, legislators and law enforcement have long taken a hard-line approach publicly, they have also found backdoor deals with the gangs useful.

The most notorious example is the “tregua entre pandillas,” or “gang truce,” which saw leaders from the three largest gangs agree to put an end to killings. Forged in 2012 among the Mara Salvatrucha (MS13), two factions of the Barrio 18 and government-backed mediators, the truce looked to upend conventional wisdom that the only way to confront the gangs was more force, with the administration of former President Mauricio Funes taking credit for murders plummeting by nearly half.

SEE ALSO: El Salvador News and Profiles

Upon its unraveling in 2014, however, murders soon spiked. And when the opaque nature of the pact and the benefits the state extended to gang members came to light, the truce slowly transformed from a political triumph to a criminal liability for those involved.

Below, InSight Crime provides a primer on the cases involving secret deals with gangs: from the trials of officials seen since the truce’s undoing to the new charges against prominent politicians.

Politicians Negotiating with Gangs

Attorney General Raúl Melara has accused several high-ranking members of El Salvador’s two major political parties of conspiracy and electoral fraud for negotiating with gang bosses for political benefit.

Those charged in the left-wing Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional — FMLN) include Benito Lara and Arístides Valencia, both former congressmen and officials in the government of former President Salvador Sánchez Cerén (2014-2019). Lara served as security minister, while Valencia was interior minister, government positions that specifically facilitated their ability to offer money and reach deals with the gangs.

Prosecutors said in a news release that Lara, Valencia and others gave the gangs $150,000 in exchange for their support prior to the 2014 presidential elections, narrowly won by Sánchez Cerén. InSight Crime previously reported on a video that shows Valencia offering to create a fund of up to $10 million for the three main gangs to implement a micro-credit program. Lara was also caught on tape negotiating with gang members.

Those accused in the rightwing Nationalist Republican Alliance (Alianza Republicana Nacionalista – ARENA), which ruled the country from 1989 to 2009, include Ernesto Muyshondt, the current mayor of San Salvador, and congressman Norman Quijano, who fell short of beating Sanchez Cerén for president in 2014 by around just 6,000 votes.

They and others offered up to $100,000 to the gangs to help influence that election in ARENA’s favor, according to prosecutors.

Quijano was the first among the string of high-ranking politicians to face accusations of electoral fraud. Video shows Quijano in a meeting with gang members, pledging money for rehabilitation centers in exchange for political support in areas the gangs controlled, according to a report from El Faro.

A special commission now must decide whether there is enough evidence to strip Quijano of his legal immunity as a congressman. Quijano vehemently denied the accusations in a statement, alleging that he is the victim of a political conspiracy.

Meanwhile, Mayor Muyshondt admitted to meeting with gang members in 2015, saying that he did so to pay the extortion fees that the gangs demanded to let him campaign in the areas under their control. Muyshondt also admitted to paying blackmail with official ARENA party funds.

All of the officials accused have since sought legal representation in El Salvador, according to La Prensa Gráfica.

The Truce Trials

Police and penitentiary officials — as well as one of the truce’s chief negotiators — have been tried twice for conspiring with criminal groups, introducing contraband into the jails and other crimes related to their roles in the gang truce.

Charged in 2016 by then-Attorney General Douglas Meléndez, they were the first high-level officials in the administration of former President Funes (2009-2014) to face criminal charges for facilitating the truce.

SEE ALSO: Coverage of El Salvador’s Gang Truce

Among the officials charged were Nelson Rauda, the former director of the penitentiary system; Anílber Rodríguez, its former inspector general; Juan Roberto Castillo, a former deputy inspector with the National Civil Police; and Raúl Mijango, the truce’s chief negotiator.

The trials, however, ended with their acquittals.

Conspicuously absent from the prosecutions were former president Funes and David Munguía Payés, Funes’ minister of security and defense who was the primary architect of the truce. Munguía Payés, in fact, was still serving as defense minister in the Sánchez Cerén administration when the first so-called truce trial took place in 2017.

The judge in that trial ultimately ruled that the officials were merely following orders from Munguía Payés and Funes. Prosecutors, however, appealed the judge’s decision to a higher court, which ordered the officials be retried.

The judge in the second trial, which ended in May 2019, again found the officials not guilty on all major charges, though the penitentiary directors were sentenced to three years of community service on minor charges for authorizing transfers of gang leaders within the prisons and allowing inmates to throw parties.

Munguía Payés testified about his role in the gang truce, saying that he facilitated the work of the negotiators and received reports from them and officials with the Organization of American States (OAS), which had supported the truce. He also said he kept President Funes informed about developments.

When asked why he wasn’t tried himself, Munguía Payés responded by saying that he wasn’t committing any crimes.

“We were developing a public policy,” he said.

But the judge questioned the Attorney General’s decision to not prosecute Munguía Payés and Funes, reprimanding him for a shoddy effort.

Chief Truce Negotiator in Prison

Former guerrilla commander and lawmaker Raúl Mijango was the chief negotiator of the truce, and the only one to find himself behind bars for it.

In 2018, Mijango was sentenced to 13 years in prison for conspiring with gang members to extort a food production and distribution company.

SEE ALSO: El Salvador’s Jailed Gang Mediator: ‘I feel defrauded’

Prosecutors said Mijango called company representatives to a meeting where he brokered a deal between them and the leaders of the three major gangs. The company agreed to provide $6,000 worth of “rice, beans, [cooking] oil, pampers and other goods” to the gangs every month. In return, gang members would allow the company’s trucks to pass through safely when they came into territories under their control.

The products — left at different drop points – were then sold by the gangs at San Salvador’s central market or other spots. Mijango advised the use of receipts to make the transactions appear legal, according to prosecutors, and even took some of the merchandise for himself.

Mijango has always maintained that by persuading the gangs to renegotiate their extortion price, he was helping phase out extortion. Previously, the gangs had been demanding some $15,000 a month from the company. Company representatives were so appreciative of the new deal that they sent one gang leader with whom they negotiated a Christmas basket and turkey.

Prosecutors insisted that Mijango was facilitating extortion, regardless of his intent.

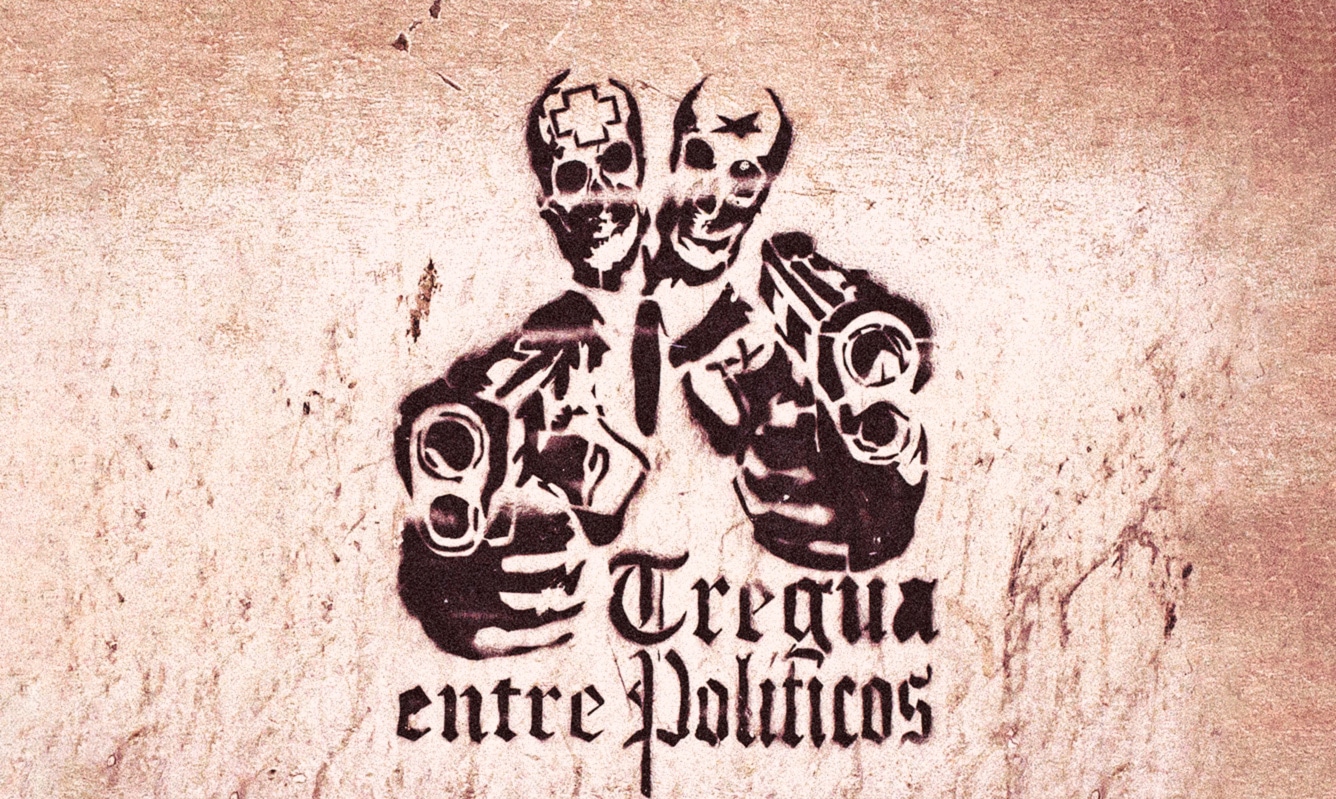

AP Photo: Stenciled graffiti painted on a main wall of the National Palace in San Salvador that reads: “Truce between politicians.”