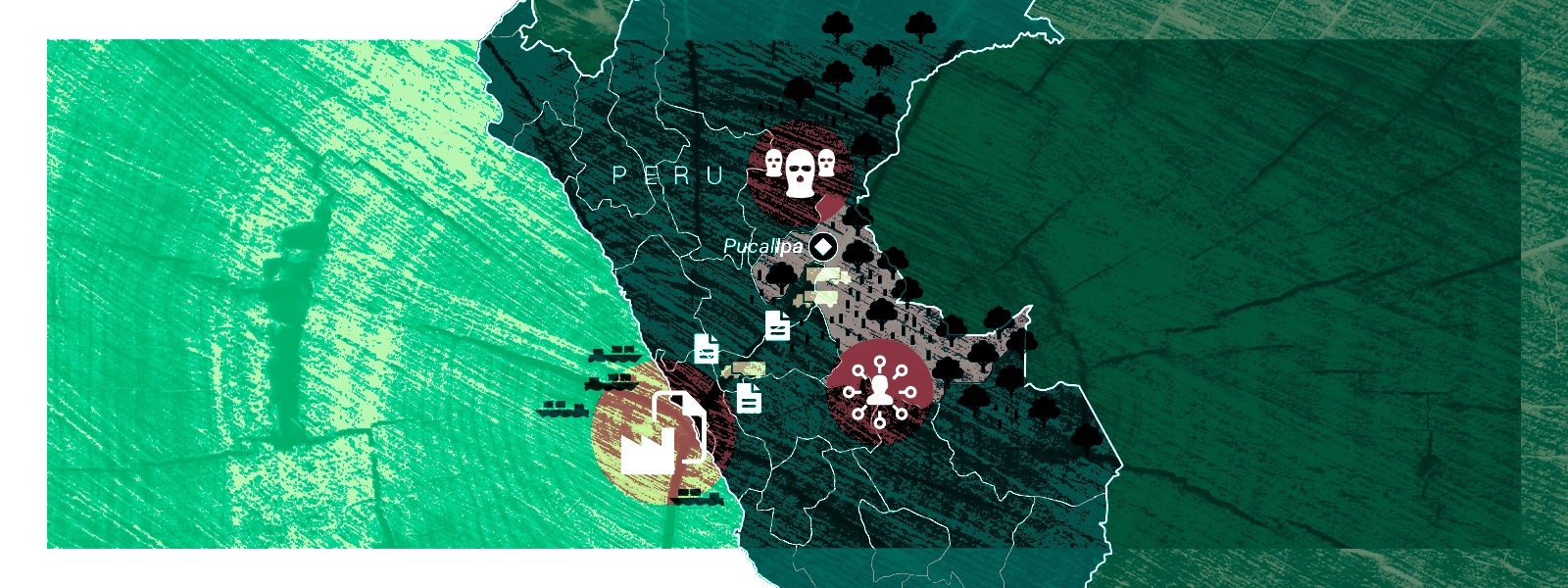

The Patrones de Ucayali, a criminal network led by a former police officer, illegally felled the forests of eastern Peru to feed domestic and international black markets. This extensive enterprise involved dozens of loggers, transporters and middlemen who brought the timber out of the jungle and took it to Lima, as well as government officials and moneymen who legalized the shipments by falsifying official permits.

Nearly eight months after the wiretaps were installed, the conversations on the phones suddenly changed. The talk of logging, laundering and shipping illegal wood stopped. Instead, the voices talked of destroying evidence and ditching phones. They knew who was listening.

By the time prosecutors executed their arrest warrants, the leaders of the network they had dubbed the “Patrones de Ucayali,” or the “Bosses of Ucayali,” had disappeared. And the first organized crime case to be brought against Peru’s timber mafias was left with the dregs of the organization, the lowly criminals that took bribes, forged paperwork and cut down trees.

*This is the fourth chapter of a four-part series on timber trafficking across Latin America, carried out over two years by InSight Crime in collaboration with American University’s Center for Latin American and Latino Studies. This investigation involved extensive fieldwork in Colombia, Honduras, Mexico and Peru, during which we interviewed dozens of government officials, members of security forces, academics, smugglers, landowners and local residents, among others. Read the entire series here.

The prosecutors investigating the Patrones de Ucayali were well aware the name they had given the network was a misnomer: In reality, the Patrones were a common mid-level trafficking network, not capos of Peru’s multimillion-dollar illegal timber trade. But they had hoped the case would send a message to those higher up, those who pulled the strings of the Peruvian state and packaged off illegal wood for international consumption. They wanted the real “patrones” of Peru’s timber mafia to know that the era of impunity had ended. Instead, they received a message in return: “We have the power.”

The Llancari Network

The investigation into the Patrones network began when police intelligence made contact with prosecutors in Ucayali’s capital city and Peru’s main timber trafficking hub, Pucallpa. They had come across some suspicious paperwork, specifically a series of what are known as Timber Transport Permits (Guias de Transporte Forestal — GTF), which had been used to move wood along the highway connecting Pucallpa to the capital city Lima.

Prosecutors formally opened an investigation in 2015. Working with the police, they sent out surveillance teams who tracked down logging camps, clandestine sawmills and storage yards. They copied documents and photographed suspects exchanging money and papers. And they tapped phones, and they listened.

As investigators connected the dots, a network began to take shape. At the head was Juan Miguel Llancari Gálvez, a former policeman and loan shark. At his side was his right-hand man, Jorge Edilberto Alvarez Choquehuanca, better known as “El Chino” — roughly translated, “the Chinese man.” Below them were teams of loggers, forgers, transporters, corrupt officials and frontmen.

In order to sell wood illegally logged from the Peruvian Amazon, the network established two supply chains: one real, the other existing only on paper.

Securing the supply was the easy part. First, El Chino recruited loggers from the near bottomless pool of local informal labor in underdeveloped Amazonian communities.

Using the financing model common to Peru’s illegal logging sector — known as habilitación — he provided them with fuel and supplies upfront for the operations, discounting the costs from the price paid for the wood. However, unlike many facilitators who use such arrangements to trick loggers into debt peonage or renege on deals when the wood is delivered, he was good to his word.

“El Chino negotiated hard, he always looked for a very low price, but in the end, he always delivered on the payments for the wood,” said Julio Reátegui, the Ucayali organized crime prosecutor who led the investigations.

The loggers were dispatched with orders to seek out and cut down “shihuahuaco” and “estoraque” — the common Peruvian names for Dipteryx micrantha and Myroxylon balsamum — tropical hardwoods prized as flooring and decking, especially by importers from Peru’s biggest international timber trading partner, China.

SEE ALSO: Peru Profile

From the camps deep in the forests, the crews shipped logs down the river on barges, processed them using illegal portable sawmills and stockpiled them in their three clandestine storage yards.

The first part of the journey by road then had to be completed without documents, so El Chino and Llancari made arrangements with trusted transport companies. El Chino would pay the truck drivers not only transport costs but also the bribe money needed to pay the police.

The network also had three police officers on their books, who would escort the shipments on their way, distributing bribes at roadside checkpoints and alerting El Chino and the transporters to the presence of patrols that were not friendly.

Once the trucks reached the Federico Basadre highway leading to Lima, El Chino would hand the drivers documents ostensibly proving the timber’s legal origins. They were then free to continue on to the waiting exporters.

How to Get the Paperwork

Obtaining those documents and establishing the paper trail that made them seem legitimate were more complex tasks for the Patrones. This was the key to the whole operation — and to the Peruvian timber trafficking industry as a whole: laundering the illegal wood into the legal supply chain.

First, they needed to set up the companies that would pose as the legal loggers and traders of the timber. One of these shell companies was registered in the name of Llancari’s wife. The rest, though, used frontmen, described in the accusation as “men of a young age, without economic means nor real guarantees to justify either capital or commercial operations of economic significance.” The company “offices” were rundown houses in the poor part of town.

“They were ghost businesses, they only existed on paper,” said Reátegui.

Llancari also used shell companies to launder payments from the exporters. The money would arrive at the company bank accounts, then the frontmen would withdraw it in cash and hand it to El Chino. In return, they received between 100 and 200 soles (around $30-60) for each transaction.

“They were receiving payments of 50,000, 100,000 soles [between $15,000 and $30,000] every month but living in situations that did not match that much money,” said Reátegui.

Next, the Patrones needed to get their hands on the right documents. For this, they tasked a specialist forger named Norma Chuquipiondo Carillo, alias “Tia Norma,” or “Aunt Norma.” The police raid on Tia Norma’s house showed the tools of her trade: falsified logging contracts, books of blank but signed processing reports from sawmills, official stamps from the forestry authorities, invoices, bank receipts and a stack of cash.

Tia Norma sourced these documents and the others she needed from corrupt contacts in legal sawmills, which function as wood laundering centers, and the General Forestry and Wildlife Directorate (Dirección General Forestal y de Fauna Silvestre — DGFFS) — the deeply corrupt local government body responsible for authorizing and monitoring timber extraction, movement and sale.

“The sawmills sell these documents to whoever wants to buy them and the engineers are corrupt,” said Reátegui. “The system is so corrupt that they do it openly, they’re not hiding it.”

By the time, Tia Norma had painstakingly constructed her paper trail, each shipment had a GTF, which showed the wood was extracted from an Indigenous community with permission to sell wood in their territory — even though the communities and their leaders had never heard of Llancari or the front businesses he operated through.

Each GTF was stamped by DGFFS engineers to show its passage through control points between those communities and the city of Pucallpa — even though the wood never came within a hundred kilometers of Pucallpa.

The GTF was also accompanied by processing documents registering its passage through Pucallpa sawmills, which were stamped by DGFFS officials to say they had inspected the shipments after processing — even though the wood was processed by portable saws in faraway clandestine storage yards.

All that remained then was for El Chino to take the documents to the crossroads where the road from the jungle met the highway to Lima, and the trucks of illegal timber met the legal paper trail.

The prosecutors and police spent over a year gathering evidence and mapping out the Patrones network. But when the phones fell dead, they were in a bind. Someone, either from the police or the prosecutor’s office, both notoriously corrupt institutions, had tipped Llancari off. But what to do?

“We decided to stop everything and wait so they would think it is a false alarm,” said Reátegui. It was the wrong move. “When we carried out the operation, none of the leadership was there.”

The Bozovich Connection

The investigations into the Patrones network stopped with Llancari. But the illegal wood they were extracting from the Amazon continued going to Peru’s principal exporters — and to the true patrons of Peru’s timber trade.

The phrase is littered over and over again throughout the indictment, “con destino Bozovich” — destination Bozovich — the oldest, most famous name in the Peruvian wood trade. However, at no point does the Bozovich family or the parent company of their business empire, Bozovich SAC, officially become part of the criminal investigation.

The reason why is made clear in the investigators’ notes from communications intercepted from July 13.

“Llancari says the truck has arrived to Lima, the volume [falsified logging permission] has come from a native community that is inspected by [logging supervisory body] OSINFOR and so, in BOZOVICH, they can’t receive the shipment with that documentation,” the notes read. “Chino says he is going to ring the guy. Llancari says to ring him and he gives him the phone number. It is a young guy that is going to answer, because the shipment has arrived, but the documentation is no good.”

It is the same protection mechanism exporters and other end users hide behind throughout the industry: As long as the documents say it is legal, and the state forestry agencies haven’t proven otherwise, then they are “good faith buyers.”

“Bozovich has the perfect cover because if they are investigated, they are going to say, ‘Well, I buy the wood from companies that are legally formed and constituted, and everything was properly accounted for so I have no responsibility.'” said the prosecutor Reátegui. “This is the scheme they use all across the country.”

The bad faith of the good faith argument was laid bare in 2017 in an undercover investigation by Global Witness. In the report, exporters who were being secretly filmed admitted they were aware the documents showed to them to secure the purchase had been falsified.

Among those exposed by Global Witness was William Castro, a timber baron who numerous inside sources say has close ties to Bozovich, and whose company is currently under investigation for timber trafficking, according to Peruvian investigative website Ojo Público.

“They present the stamped papers, you look and you buy, but what is the guarantee? The stamp of these regional governments has no guarantee,” Castro said.

However, purchasing wood from networks such as the Patrones represents just a fraction of these exporters’ business. Much of their wood comes from elaborate and sometimes transnational networks of companies set up by associates and lawyers that keep their hands — and their money — clean.

These networks of logging companies, timber traders, sawmills, machinery rental companies, storage yards and transport companies allow big companies to directly finance illegal loggers and move the timber they produce along the supply chain, but all from a safe distance.

“The loggers work for the exporters and for the intermediate companies, which are also connected to the exporters,” said Daniel Linares, Chief of Operational Analysis of Peru’s Financial Intelligence Unit (Unidad de Inteligencia Financiera — UIF), which has turned its sights on money laundering in the timber trade in recent years.

“[The exporters] have people in the zones where extraction is prohibited, but there is wood they are interested in exporting. Once they find it, they invest with machinery, personnel, and in the logging activities to extract the wood and convert it into exportable pieces.”

These investments are funneled as payments made to the front companies, says Rolando Navarro, the former president of the Agency for Supervision of Forest Resources (Organismo de Supervisión de los Recursos Forestales — OSINFOR), the state body that inspects logging operations and investigates violations of forestry law. The exporters then coordinate activities from forest to port using their own agents, who appear on company books disguised by vague accounting terms like “personnel services,” he says.

“They put their people in the field to guarantee the wood leaves and arrives at its final destination,” Navarro explained. “[The exporter] has to have a chain of custody and personnel in the field that are constantly informing them how many trees have been cut down, which species, which ones are in which storage yards, so that they can project when this wood is going to be in their hands and they can program their exports. They work like this at a national level.”

Investigators began to expose the workings of these networks in the multi-agency anti-illegal timber operation known as Operación Amazonas in 2014 and 2015, which Navarro helped lead. Investigators’ analysis of certain export companies uncovered internal movements of cash and wood disguised as external dealings by networks of what appear to be independent timber traders, sawmills and service providers. When they looked more closely at these businesses, they found shell companies whose offices were houses or even ramshackle shacks, who shared managers, legal representatives and directors, and whose capital flows stood in stark contrast to their declared capitalization.

The Bozovich Network

While allegations of illegal timber trading have swirled around Bozovich for more than 15 years, the family has never faced criminal charges. However, InSight Crime’s investigations into the Bozovich network reveal a profile strikingly similar to what investigators describe.

With the aid of investigators from Global Witness, the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) and the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), InSight Crime obtained documents detailing the movement of over 8,000 timber shipments belonging to Bozovich within Peru covering the years of 2006 to 2016, and over 400 exports from 2015.

The data shows hundreds of shipments of wood harvested from logging concessions on OSINFOR’s Red List, which flags timber sources that had undergone or were undergoing sanctions for falsification of data or other forestry law infractions, and many more that had undergone no inspections at all.

However, the data also shows something else: a paper trail leading to a circular supply chain in which a handful of names and addresses appear over and again in businesses connected to Bozovich.

Nearly 70 percent of the 2015 exports were of wood coming from just two companies that dealt only with Bozovich: EP Maderas, and Comercial AJAE. InSight Crime traced a further 1,011 timber shipments moved from EP Maderas and AJAE to Bozovich. Of these shipments, 49 percent came from logging zones on OSINFOR’s Red List, while a further 13 percent had not been inspected at all. The same year, AJAE was twice sanctioned for trading illegal wood.

When InSight Crime visited the address listed as the Lima offices of AJAE, we found an apartment in a residential compound registered to a local family. EP Madera’s address, meanwhile, is registered to the legal practice of Bozovich’s lawyer, and the lynchpin of their network, José Alfredo Biasevich Barreto.

A closer examination of the companies reveals their position in a labyrinthine network connected to Bozovich. Among EP Maderas’ legal representatives are Pedro Jose Cuestas Torres, who holds positions in seven further timber companies, and Juan Armando Angulo Davila, who also happens to be general manager of AJAE and legal representative for three of the same companies where Cuestas Torres’ name appears.

SEE ALSO: Timber Laundering in Peru: The Mafia in the Middle

One of these timber companies is another Bozovich supplier that appears in the Callao data. That company shares an address with yet another timber company, whose executive manager is José Alfredo Biasevich Barreto. AJAE’s legal representative, meanwhile, also happens to be a legal representative of one of the two Bozovich subsidiaries that hold forestry concessions, whose other legal representatives include the Bozovich brothers themselves and José Alfredo Biasevich Barreto.

The Bozovich business loop extends transnationally. The family own timber import businesses in both the United States and Mexico. And they own offshore businesses in tax havens managed by Mossack Fonseca, the law firm made notorious by the “Panama Papers” leaks for its ability to hide stolen money, corruption proceeds and drug trafficking profits.

Reports by Peruvian investigative website Ojo Público uncovered suspicious financial transactions funneled through these offshore businesses. Once again, the paper trail leads back to José Alfredo Biasevich Barreto.

Biasevich is listed as the general manager of Latitud 33, a company whose commercial address is his law office, even though it is registered on the island of Niue. According to Ojo Público’s Panama Papers investigation, in 2008, offshore money transfers were used for Latitud 33 to buy the shares of the sawmill Industrial Satipo for $499,000 — a purchase that raised suspicions as Biasevich had also been an executive of Industrial Satipo, and because just one year later the company was shut down by tax authorities.

The money for the purchase was transferred to Oswaldo Frech Loechle, another legal representative of the two Bozovich forestry concessions, as well as a transport company. And the loop continues: the legal representative of the transport company is the general manager of a machinery rental company. And the legal representative of the machinery rental company is also a legal representative of the two Bozovich forestry concessions and the same string of timber companies where the names Biasevich, Cuestas Torres, Angulo Davila and others appear over and over again.

It is the transnational wing of the Bozovich empire that could represent their biggest vulnerability. In 2017, Ojo Público revealed that Peruvian prosecutors were investigating Mossack Fonseca and their Peruvian clients, including the Bozovich family, for money laundering. The family’s US subsidiary, meanwhile, could also leave them exposed to prosecution under the Lacey Act — a US law that closes the “good faith” loophole by stating that simply possessing documents that say your wood is legal is no excuse for trading illegal timber.

The Business of Power

The Bozovich family is not only in the wood business. It is also in the power business.

The timber industry has co-opted the Peruvian state from local governments and congressmen in logging hotspots to the state agencies responsible for protecting Peru’s forests and regulating the sector. And the Bozovich sit at the center of this industrial-political axis.

Nowhere is this more apparent than the Mesa Forestal — the roundtable where key actors from the public and private sector meet. At the Mesa Forestal, the private sector is represented by two men: the president of Peru’s Exporters Association (Asociación de Exportadores — ADEX), and the president of the wood industry committee of the National Society of Industries (Sociedad Nacional de Industrias — SNI), who is also, as of April 2018, a member of international sustainable forestry certifiers the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). The first of these is Eric Fischer, a Bozovich executive. The second is José Alfredo Biasevich.

Industry insiders and both current and former officials, speaking anonymously to InSight Crime, say Fischer and Biasevich set the Mesa Forestal agenda and, with the complicity of forestry officials and even ministers that attend meetings, have diverted it away from discussions of industry regulation.

Instead, the Bozovich agents, their fellow timber baron representatives and their state cohorts turned their sights on OSINFOR, the institution that has exposed the scale of illegality in Peru’s timber supply chain and threatens to do what they fear most: prove that traceability in Peru’s timber trade is possible.

“We had a clear confrontation with all the mafia and corruption networks from all over the country, but the hardest and most upsetting thing was that from the day I entered OSINFOR, this same conflict also came from within the state,” said Navarro, who was controversially removed from his position in 2016 after a top-level political intervention by timber barons and their political allies.

The latest move against OSINFOR came in late 2018. The government pushed through controversial reforms that would end the institution’s autonomy and independence from political meddling by bringing it under the control of the Ministry for the Environment; at the time headed by Fabiola Muñoz, a minister with a history of intervening in investigations on behalf of timber companies. The push for the reforms, according to Ojo Público’s investigations, was led by Eric Fisher and José Alfredo Biasevich.

However, in April 2019, the government performed a U-turn, annulling the reforms following a public outcry and, critically, intense pressure from the US government, which said the measures violated conditions laid out in trade agreements between the countries. For campaigners, the reprise was a welcome sign that the power of the timber lobby can be curbed. But the feeling that OSINFOR is under siege remains.

“This what they are looking to do — enter OSINFOR, capture OSINFOR and once it is captured, control the discourse among all the sectors of the state,” said Navarro.

Bozovich declined repeated requests for an interview with InSight Crime and did not respond to written questions.

The Case Unravels

The prosecutor that carried out the Patrones investigation is well aware that the case left the upper echelons of the illegal timber trade untouched.

“Llancari was mid-level,” said Reátegui. “There are much bigger players but they are legal, formal businesses, and they move a lot more money, so they have much more protection from the politicians and the judges.”

Despite this, and despite the fact there was still no sign of Llancari, his wife and El Chino, the case represented a first opportunity at bringing a successful organized crime prosecution of a timber trafficking network, which would represent a landmark achievement in tackling Peru’s illegal wood trade.

The case began a tour of Peru’s courts — shunted from Pucallpa to the environmental court of Huanaco and then to the national organized crime court of Lima.

The judge’s ruling came in July 2018. But instead of the blow against timber trafficking prosecutors had hoped for, it was a blow struck for impunity: The judge absolved everyone. Not because they were innocent of the accusations, but because the judge decided that the prosecutors had not proven that any crime had been committed.

The ruling was a mess of contradictions and legal contortions.

Specifically, the judge argued, Peru’s forestry law only prohibits trafficking protected species such as mahogany and cedar, ignoring that the law had changed in September 2015 — eight months before the arrests — to include any and all tree species. The judge also refused to allow as evidence the seized wood, saying it could not be taken into account as it had not been tested to prove its species, and that prosecutors had not proven it was illegal because they had not shown where it had actually come from.

The judge also disregarded the conspiracy charges. The defendants cannot be convicted of the crime of “facilitating, acquiring, collecting, storing, transforming, and transporting wood of illegal origin,” he declared, as none of them had done each one and every one of those activities.

The ruling stunned both Reátegui and the Lima prosecutor who took on the case, Irene Mercado. Both are guarded in their conclusions, but their suspicions are thinly concealed.

“I’m very worried because I do not believe that a judge would make such an evaluation lightly,” said Mercado.

Mercado immediately drafted an appeal. She argued that even though the investigation had begun before the new law came into effect, the Patrones had continued to traffic wood for eight months afterwards, and that, besides, logging any species without permission was a crime under the old law, even if trafficking them wasn’t. The appeal also asked why the dispute over the trafficking law would also lead to the bribery and corruption charges being dropped.

The tone of the appeal was one of astonishment at the judge’s reasoning.

“The judge cannot demand the Attorney General’s Office specify the origin of the illegal wood given that this is impossible; it would be the same as requiring that it is specified where a rock of illegal gold came from or which part of the sea every single fish from an illegal fishing operation came from,” it reads. “If the exploitation of the wood were legal it would not have been necessary to doctor the timber transport permit nor bribe engineers nor police at control points.”

However, the appeal never got filed. Instead, the Superior Prosecutor decided the failure lay with the case the prosecutors had built and so they would accept the first ruling. The decision left Mercado deeply frustrated.

“Let’s go to appeal. Let the court decide if I’m right or not, but let’s go to appeal and debate it,” she said. “But unfortunately, we didn’t get the chance.”

Peru’s first organized crime timber trafficking case had failed. However, for the prosecutors, this setback has not spelled the end of attempts to treat the illegal timber trade as an organized crime problem, and several more cases are currently working their way through the courts. None of them, however, reach the timber barons at the end of the supply chain.

“In Pucallpa, everyone handles illegal wood, absolutely everyone,” said Reátegui. “And the bigger they are, the more protected they are. That is the reality.”