The mayor of Moyuta, Guatemala, knows how to do politics and business along the rough and tumble Guatemalan-Salvadoran border.

On the night of May 28, 2017, an El Salvador Navy vessel was on routine patrol when its crew tracked down a fishing boat just over 200 nautical miles south of Acajutla, a seaport city on the country’s Pacific coast. The fishing boat tried to flee the patrol and began off-loading cargo into the ocean. After a short chase, the Navy caught the ship and boarded the vessel. In all, they found 840 kilograms of cocaine on the ship and in the water.

Worth $21 million in the retail drug market, according to estimates made by Salvadoran authorities, the operation made headlines in El Salvador as the Navy’s biggest cocaine seizure. The news then spread to neighboring Guatemala, where local press noted that among those arrested by El Salvador authorities was the brother of Carlos Roberto Marroquín Fuentes, the mayor of Moyuta, a municipality in the southeastern Jutiapa province, just over an hour’s drive from Acajutla.

Moyuta lies on the southern cusp of Guatemala’s central highlands, where forested mountains and volcanoes fall away into arid plains and sandy beaches along the Pacific coast. Despite its serene appearance, Moyuta has been rocked by violent feuds between rival drug-trafficking families vying for control of local politics, and by extension the coveted transnational smuggling routes that crisscross the municipality.

For Mayor Marroquín, seeing his brother arrested was another setback in his efforts to fend off the persistent rumors of his involvement in the international drug trade. To be sure, Guatemala’s then-interior minister refused to rule out the mayor’s participation in his brother’s operations, which only cranked up the pressure.

But Marroquín was accustomed to weathering the storm. In fact, he was one of the few constants during a period of unprecedented political violence, underscored by cold-blooded murders and brazen assassination attempts, which had elevated Moyuta’s criminal disputes to legendary status.

A Border Town with Border Problems

Since becoming mayor in 2011, Marroquín has made a habit of hosting extravagant beach festivals in his hometown of La Barrona, Moyuta, with entertainment including bikini pageants, wet T-shirt contests and live DJs.

A promo video for the 2015 installment, held in the run-up to that year’s municipal election — which, according to Soy502, cost Q99,000 (approx. $13,000) in municipal funds — featured Marroquín on a boat surrounded by dancing, bikini-clad women. The events date back to 2012, when the mayor purportedly gave revelers the chance to ride for free in one of his speedboats.

Marroquín’s penchant for fun has been noted by his peers, among them the former president of Guatemala’s national association of municipalities (Asociación Nacional de Municipalidades – ANAM), Edwin Escobar, who described him as a “gregarious guy” who is “always in a party mode.”

The two men have a complicated relationship. Marroquín briefly backed Escobar when he began running for president in 2018, before changing tack and publicly accusing Escobar of corruption later the same year, according to elPeriódico. Escobar distanced his party from the mayor in an interview with InSight Crime, saying “we never took him in.”

But away from the festivities, the violence in Moyuta was a reminder of the lethal battles waged between rival clans vying for territorial control in Jutiapa and the wider Pacific – a region pivotal to the transnational cocaine trade.

A predominantly rural area with an estimated population of 45,000, Moyuta is split into temperate highlands where farmers grow coffee and other basic crops, and the hot, coastal lowlands that house cattle ranches and fishing villages of the type where Marroquín grew up.

A coastal highway linking Moyuta to El Salvador brings with it the free-flowing trade of livestock, crops and everyday goods, and has spurred the emergence of restaurants, repair shops and other local businesses. Like other areas along the dry, southern provinces, cattle ranchers and their minions patrol the area’s arid plains riding horses in cowboy hats and leather boots — Guatemala’s version of the Wild West.

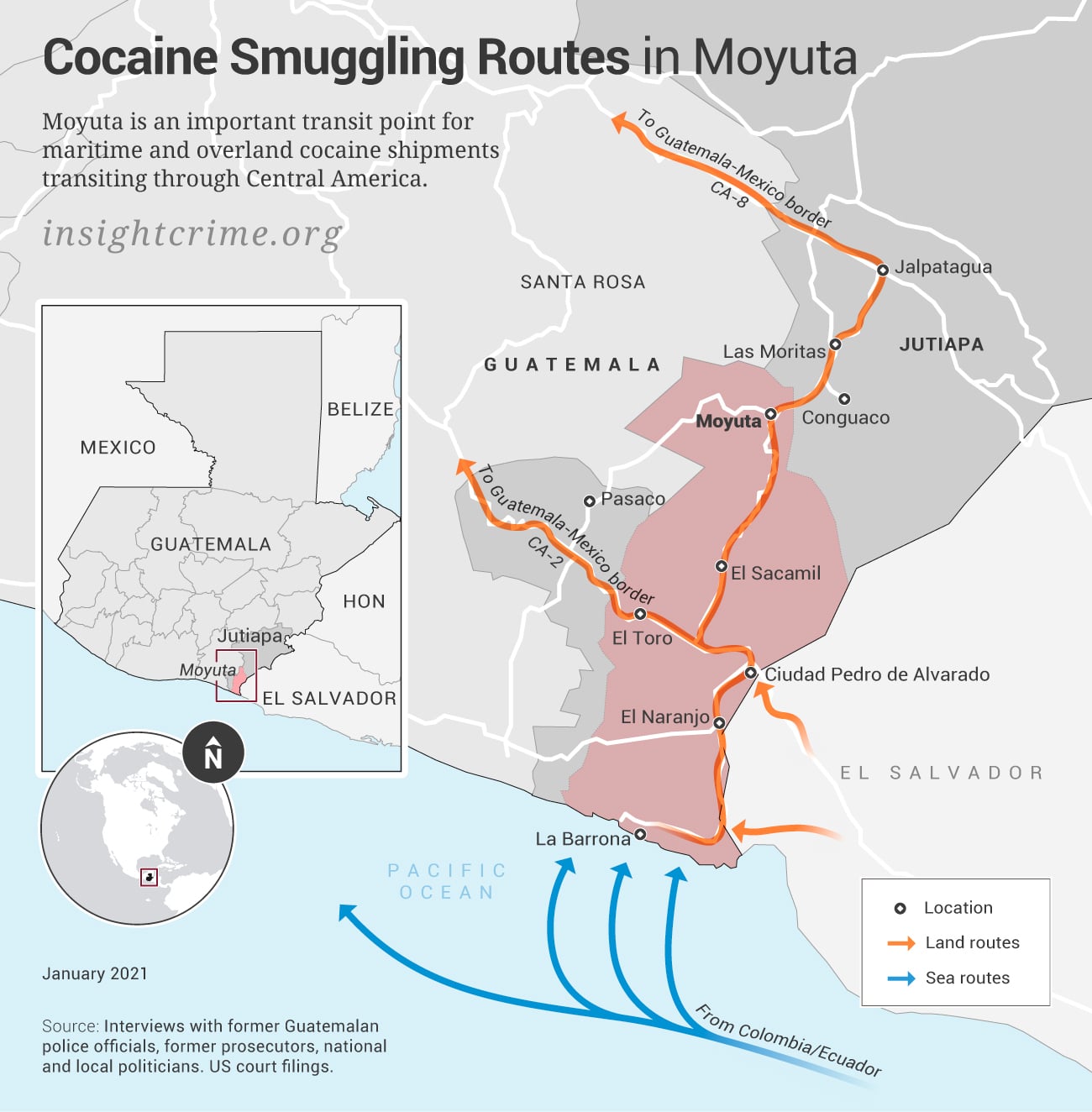

But Moyuta’s real fortune lies in its illegal economy — more specifically its coveted drug-smuggling routes. A largely unmonitored stretch of the Pacific coast provides a convenient drop-off point for South American cocaine shipments, while the municipality’s porous eastern border connects it to a part of El Salvador where freight networks have long specialized in delivering cocaine to partners in Guatemala. In Moyuta’s case, these cargoes come via the Pacific highway that enters Pedro de Alvarado, a small but economically important town on Moyuta’s eastern border with El Salvador.

There are also a host of bodegas and farmhouses in and around Moyuta, ideal for storing drug loads that cannot be shipped immediately through the area, according to Guatemalan prosecutors. Moyuta, and the department of Jutiapa as a whole, has thus become prime real estate for drug traffickers.

Jutiapa is one of the main entry points for cocaine shipments coming via sea from South America. The department also has a lengthy border with El Salvador, with three leaky customs checkpoints and a plethora of unmonitored crossings, providing ample opportunity to move drugs into Guatemala.

In times gone by, the department was home to major players in the Central American drug trade — mostly notably the León family, a clan of cattle rustlers and car thieves turned drug kingpins that specialized in theft and resale, as well as transporting cocaine through Guatemala via the eastern border with El Salvador and Honduras.

But the panorama along the border changed when the Mexican criminal organization, the Zetas, murdered the clan’s leader, Juancho León. The atomization that followed paved the way for smaller drug clans to assert their control in different parts of the department. And these clans need City Hall to ensure security forces and prosecutors are kept at bay.

A Bloody Campaign

Roberto Marroquín came from La Barrona, a poor fishing village on Moyuta’s Pacific coast. An athletic man who often spikes his black hair, keeps a well-groomed goatee, and maintains a tan befitting of someone who grew up on the beaches of the Guatemalan Pacific, Marroquín likes to talk more about his background as a cattle rancher who raised the funds for his political campaigns through a family ranching business passed down from his grandfather than about his time on the coast.

But there are other, more acrid accounts of his backstory. Reconstructing Marroquín’s early life is difficult. Like his father, it appears Marroquín was raised as a “lanchero,” a local term for the hardworking boatmen who use dinky, wooden motorboats to fish, transport people or run errands. Many lancheros in La Barrona also collect packs of cocaine, dropped into the ocean by airplanes and speedboats off the coast of Moyuta.

At some point, according to an account from sworn affidavits in a court filing in the case of an asylum seeker who fled to the US from Guatemala due to drug violence, which InSight Crime accessed, the family’s fleet of boats increased significantly. The asylum seeker, who himself admitted to being connected to the drug trade, claimed the boats were used to scoop up and transport illegal drugs. One former high-ranking Guatemalan prosecutor who investigated drug trafficking in Jutiapa also said the Marroquín family was for years one of many involved in drug trafficking in the department. Political rivals say the same.

Still, none of them offer evidence, and Marroquín has not been charged with any crimes. In past statements to the press, he has also denied any connection to the drug trade.

InSight Crime approached the mayor, and he agreed to speak with us but only in person. Due to Covid-19, however, InSight Crime did not travel to Moyuta to meet with him.

In a brief text exchange, Marroquín reiterated that he would only do an interview face-to-face. He added that during his time as mayor he has “fought against organized crime within [political] institutions and outside of them,” adding that has “brought order across the board” in the municipality.

SEE ALSO: Border Crime: The Northern Triangle and the Tri-Border Area

At some point, Marroquín got more involved in local politics. He became the president of a local development council in 2008, which opened the door to run for mayor in 2011.

It was a bloody road to City Hall. His chief rival in the race was Mayra Lemus Pérez, the sister of the former mayor, Magno Lemus. Under Magno, the Lemus family had “controlled a good portion of Jutiapa trafficking and connections to Mexican cartels,” according to Guatemalan police investigations cited in the same asylum filing. And locals told elPeriódico that he thought that becoming mayor would help facilitate his illicit business. But Magno’s time in office ended abruptly when he died of a heart attack in October 2009, paving the way for Mayra to run in his place.

Then there was the Rodríguez family. Rony Rodríguez, a candidate for Moyuta municipal council in the 2011 elections, had allegedly taken control of the area’s trafficking routes following Magno Lemus’ death, according to the sworn affidavits in the same asylum filing as well as Guatemalan police reports cited in that case. But the competition was fierce. Politics, as was evident during the 2011 mayoral campaign, had become something of a blood sport in Moyuta.

The fight broke into public view in spectacular fashion. On February 18, 2011, seven months before the municipal elections, Mayra Lemus stopped off at Los Cuernos Hotel and Restaurant in Pedro de Alvarado. There, a group of ten suspected hitmen, armed with AK-47 rifles, twelve-gauge shotguns and pistols, barged in and sprayed the patrons with bullets, leaving a trail of dead that included Mayra, one of her security guards, the owner of the restaurant and five others, according to local press and investigations carried out by the Guatemalan Attorney General’s Office.

Documents from the MP obtained by InSight Crime, name Roberto Marroquín and one other individual as suspects in an investigation into the massacre at Los Cuernos. According to one anonymous witness cited by the investigators in the MP documents, Marroquín worked with Mayra’s brother, Noé Lemus, who had had falling out with his siblings, to arrange the ambush.

The witness said the shooting was an act of revenge after Mayra had tried to oust Marroquín from the upcoming elections by telling police that he was carrying firearms with a doctored license. Marroquín, the same witness said, was also “engaged in the trafficking of various types of drugs.”

The MP tried to corroborate the account. The documents say MP investigators requested permission to raid a series of properties linked to Marroquín less than a week after the massacre, where they suspected that he and Noé were hiding, and where the candidate was allegedly storing drugs, according to the witness.

Three of those properties were in Marroquín’s hometown of La Barrona. Another — a guns and ammunition store called Armería El Jaguar, which was also allegedly the property of Marroquín, as well as the local office of Marroquín’s then-political party, the National Change Union (Unión del Cambio Nacional – UCN) — were in a neighboring town.

But the investigation stalled for unknown reasons, and there is no evidence the raids ever took place. Instead, Marroquín continued his run for mayor and later denied all accusations of murder.

After Mayra’s murder, her sister, Marixa Lemus Pérez took her place as the candidate. Known more popularly as “La Patrona” (The Boss), Marixa was not easily frightened. She had played a supporting role in her big sister’s political ambitions, coordinating the logistics for her campaign, and had a role in the trafficking side of the family business.

Now, Mayra’s death had thrown Marixa, a tough woman with thick black hair and a stern gaze framed by heavy brows, to the front of the stage. And she built a coalition, allegedly accepting funding from Rony Rodríguez, according to the asylum case filing and a rival politician.

The alliance again threatened Marroquín’s chances, according to the same court documents in the asylum case and the former high-ranking Guatemalan prosecutor. In June 2011, three months before the election, Rodríguez, was shot and killed by armed assailants.

Marroquín continued his campaign and in September 2011, won the election with over double the votes of the runner-up, Marixa. Moyuta had a new mayor, but the war was just beginning.

Three Attacks

The first time someone tried to kill Mayor Marroquín was on November 19, 2013. He was traveling in an armored vehicle around ten kilometers south of the town of Moyuta, the municipality’s administrative capital, which goes by the same name as the municipality. As his car reached a bridge on the road, it was ambushed by a group of balaclava-wearing gunmen who sprayed the vehicle with bullets. Marroquín survived unscathed, but it was a sign of things to come.

Less than a month later, a rival group allegedly led by La Patrona buried three bombs under a bridge the mayor would be crossing on the way to his home in Pedro de Alvarado, according to MP investigations obtained by elPeriódico. This one was an inside job: Local police had been helping source firearms for the group and, in other cases, passed on information about Marroquín’s movements to La Patrona’s team, according to the elPeriódico investigation. The crew had also equipped themselves with AK-47 rifles and grenades as part of the ambush.

But the plot was foiled when, for unknown reasons, the bombs failed to detonate, so the assailants ditched their weapons in a bag under the bridge and fled. Once again, Marroquín emerged unscathed.

For some, it was a sign of the importance of City Hall in controlling the drug trade.

“There are multiple benefits that come with being mayor,” a former high-ranking member of the Guatemalan national police told InSight Crime. “You have an institution that can easily be instrumentalized to guarantee impunity.”

Mayors can, for example, task security officials with work that can distract them when drug shipments are passing through their territory. They can place the full force of local counter-narcotics efforts on their rivals.

State security forces can also protect the mayor. Marroquín, for instance, had a rotating team of 16 police officers on his personal detail; the mayor’s entourage also included armored pick-up trucks.

In addition, mayors can help traffickers launder proceeds, mostly via their allocation of lucrative public works contracts, trash-collection contracts and other maintenance projects to companies connected to drug trafficking interests.

It’s difficult to prosecute mayors or their allies. Mayors rub shoulders with congressmen, prosecutors and judges, all of whom can pass on vital information on national anti-drug operations or investigations affecting their territory. And mayors have immunity while they are in office.

For all the rumors and investigations, Marroquín, for example, has never been charged with a crime. And when last consulted just prior to publication, sources in the police and MP said they know of no active investigations into the mayor.

“Roberto is just someone that is necessary for them to keep control of the territory,” Escobar, the former ANAM president, told InSight Crime, referring to how regional kingpins use local political partners to access and control smuggling routes in a particular territory.

Marroquín has blamed Marixa Lemus for the attacks, and in April 2014 Guatemalan authorities arrested and charged her with kidnapping, murder-for-hire, and forming part of a criminal organization, among other charges. But there was another attack to come. On November 2, 2014, as the mayor, his wife and two bodyguards made their way home, an armed group emerged from behind some bushes and began firing. Marroquín’s bodyguards returned fire.

This time the mayor was hit in the shoulder, his bullet-proof vest preventing more serious injury. His wife and a bodyguard were also injured in the crossfire, and, along with Marroquín, were taken to a hospital where the assailants again tried to attack them but failed to take out their target. The Moyuta mayor also holds Lemus responsible for the third attack.

Soon after, Marixa Lemus was found guilty, and in March 2015, authorities sentenced her to 94 years in prison.

In September 2015, Marroquín cruised to reelection.

Lemus, meanwhile, continued plotting.

Porous Borders

The nighttime arrest of Jorge Marroquín, off El Salvador’s Pacific Coast in May 2017, placed the spotlight firmly on the family’s potential role in the cocaine trade. That the brother of a border-town mayor was captured with a record cocaine-haul just hours away from the latter’s jurisdiction inevitably raised all too familiar questions about the ease with which small, politically-connected drug clans manage cross-border narcotics operations along the Central American isthmus.

For decades, Central American traffickers have taken advantage of deficient border controls to hop between countries. Back in the 2000s, for example, an infamous Salvadoran trafficker named José Adán Salazar Umaña, alias “Chepe Diablo,” appeared in police investigations in the Guatemalan Pacific and on the eastern border with Honduras. Chepe Diablo was the alleged head of the Texis Cartel, for years a main supplier of cocaine for Guatemalan groups operating in the provinces which border El Salvador.

The transient nature of the narcotics trade is the logical result of a supply chain that relies on successive, often small networks of drug traffickers who control different portions of the cocaine routes that cross Central America by land, air and sea, and who work together to make sure that shipments pass over each border unhindered on the way to Mexico and the United States. Many of them have municipal power beds. Salazar, for instance, had allies in the Metapán City Hall in El Salvador.

Marroquín’s may also be one of these small networks. Marroquín’s brother was arrested at high seas near the port of Acajutla, El Salvador, a place where drug trafficking is rampant. A current MP prosecutor who previously investigated Jutiapa’s cartels told InSight Crime that at some point all of the Moyuta families, including Marroquín’s, were investigated for possible links to the Texis Cartel.

SEE ALSO: Guatemala Mayor’s Brother Tied to Major El Salvador Cocaine Seizure

Jorge Marroquín, along with four other Guatemalans and an Ecuadorian also arrested on the same vessel that night in May 2017, were eventually tried and found guilty of drug trafficking in 2019. Currently, the mayor’s brother is serving a 15-year sentence for drug trafficking in a Salvadoran jail.

For his part, Roberto Marroquín, continued his political career apace. He became the president of Jutiapa mayors for ANAM in 2016, an influential four-year position that put him in contact with Escobar, who at the time was preparing a bid for the Guatemalan presidency with his newly-created Citizen Prosperity party.

Escobar claims that Marroquín wanted to join the party “to make sure he was close to the next president,” a common strategy employed by mayors who rally support for presidential runners in their areas of influence. In exchange, mayors try to get their allies put on congressional candidate lists, which helps them secure lucrative public works contracts once their chosen candidate gets into power.

Whatever relationship the pair had seemingly fell apart before elections. Marroquín was excluded from the party, according to Escobar, sparking a public fallout in December 2018 that saw the Moyuta mayor withdraw his support for the candidate and request that the county’s General Comptroller Office’s inspect the finances of Escobar’s ANAM. Escobar responded with a tweet hinting at Marroquín’s family ties to drug trafficking.

Securing Power

Other ghosts were also chasing Marroquín.

Marixa Lemus first escaped prison on May 20, 2016, slipping past the guards at the Santa Teresa penitentiary for women in Guatemala City. Once outside, she tried to navigate her way through the steep ravines that slice through the capital city but was captured in a nearby forest about an hour after the guards realized she was gone.

Marixa was later transferred to a military prison, also in the capital, which houses some of the most famous Guatemalan prisoners, including former president Otto Pérez Molina, who is currently jailed on corruption charges and awaiting trial.

Undaunted by her high-profile surroundings, Lemus escaped again May 12, 2017, this time bamboozling the wardens by disguising herself as a guard. (The ploy would cost the country’s prison system director his job.) Naturally, Lemus made a dash for neighboring El Salvador.

Back in Moyuta, the escape rattled Marroquín, who told the Guatemalan press that Marixa was looking to restart her criminal operations in the municipality. (Prior to her second flight from prison, Marroquín had spent Q243,000, about $31,000, in municipal funds to armor-plate his pick-up truck, citing a “climate of insecurity” to justify the expense.)

Lemus, however, was arrested just under a fortnight later in a housing estate outside the town of Ahuachapán, El Salvador, not far from the border with Jutiapa.

Thereafter, Marroquín tightened his grip on Moyuta.

“That sector [Moyuta] is basically controlled by the mayor and his family,” the former police official told InSight Crime when asked to comment on the current panorama in Jutiapa.

Marroquín joined the incumbent National Convergence Front (Frente de Convergencia Nacional – FCN-Nación), running alongside Patricia Sandoval, a Jutiapa congresswoman then seeking re-election whose family is also rumored to have links to drug trafficking, according to an elPeriódico investigation. The congresswoman’s former husband was extradited to the US and sentenced to 17 years in prison on drug trafficking charges and her brother was arrested in 2014 for his suspected participation in a drug trafficking ring, as per the same investigation.

Running with the ruling party, Marroquín allegedly benefited from a nationwide fraud scheme that saw FCN officials use state-funded aid programs destined for impoverished Guatemalans to garner votes during election time, according to a separate elPeriódico investigation. His municipal team was responsible for distributing food coupons in Moyuta as part of a social program for tackling seasonal hunger, the investigation alleges. The FCN has denied any wrongdoing.

Marroquín also allegedly helped finance a political ally who was running for congress with The National Union of Hope (Unión Nacional de la Esperanza – UNE), according to Edwin Escobar.

The pre-election jostling was typical of the Guatemalan political system, defined by fickle, often relationships of convenience and corrupt schemes that serve to further individual agendas, rather than any notable ideological commitment.

What’s more, one rival politician said that the strongest candidates for mayor are largely scared to run against him, for fear of reprisal, in the wake of his bloody feud with La Patrona. With no serious opponents, Marroquín comfortably won a third term in June 2019, with almost twice as many votes as the next candidate.

His alleged UNE ally became a congressman for Jutiapa, and his FCN running mate, Sandoval, secured re-election. With his well-placed connections, a defeated rival, and another four years of political immunity shielding him from criminal investigation, Marroquín appears to be in his strongest position yet.