A top US anti-drug official has cautioned that “bilateral political problems” could result from differences of opinion between the United States and Colombia about how to deal with rising cocaine production in the context of the ongoing implementation of a peace agreement with the FARC guerrilla group.

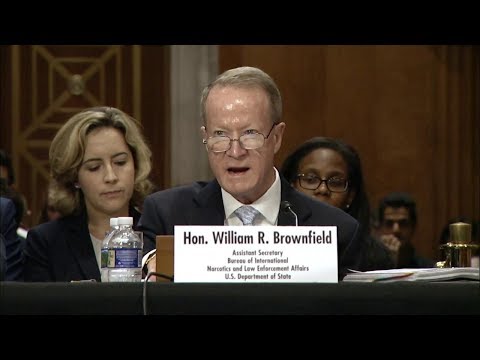

At a US congressional hearing on August 2, State Department official William Brownfield offered strong but controversial recommendations on how to curb Colombia’s booming cocaine production, which stand in contrast to the Colombian government’s planned approach to the issue.

According to the assistant secretary for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) and former ambassador to Colombia, the United States has a “limited window of opportunity to roll back the recent troubling narcotics trends” in Colombia, which he said had experienced a 200 percent increase in cocaine production over the past three years.

Brownfield stated that cocaine use has simultaneously been rising in the United States, with 2015 seeing the highest number of cocaine-related overdose deaths in almost a decade.

SEE ALSO: Coverage of Cocaine Production

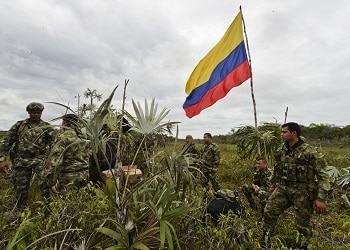

The assistant secretary laid out the main aspects of Colombia’s new drug policy as outlined in the peace accord with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC), which focuses on substituting coca with legal crops and developing infrastructure in rural areas. He explained that legal and political obstacles prevented the United States from backing those elements of the accord.

“The United States is not currently supporting the Colombian government’s voluntary eradication and crop substitution program because the FARC is involved in some aspects of the program and remains designated as a Foreign Terrorist Organization under several U.S. laws and sanctions regimes,” he said.

Brownfield also pointed to the resource limitations of Colombia’s strategy.

“We are strongly encouraging the Colombian government to limit the number of voluntary eradication agreements they negotiate and sign to make implementation feasible,” he said. “Voluntary eradication agreements must also have expiration dates so the security forces can forcibly eradicate in farms where coca growing communities fail to meet their obligations.”

Colombia aims to eradicate 100,000 hectares of coca crops by the end of the year through a 50-50 mix of crop substitution and forced eradication.

Moreover, Brownfield argued that the “Colombian leadership must find a way to implement a robust forced manual eradication effort” to encourage farmers to abandon illicit crops.

Following the hearing, Brownfield told the press, “If we don’t reach an acceptable solution for both countries reasonably soon, we’re going to see bilateral political problems and this is what I want to avoid.”

InSight Crime Analysis

Brownfield’s comments show that the United States remains committed to a traditional approach to counternarcotics efforts — one that has had little overall success, and is at odds with the Colombian government’s stated strategy. But the political and financial backing of the United States is important to the future of the FARC peace process, making it difficult for Colombia to contest or simply ignore US policy preferences.

Colombian security analyst John Marulanda believes these paradoxical interests have put the administration of Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos between a rock and a hard place.

“The government is trapped between the political necessity to keep its commitments to the FARC … and to satisfy the reiterated concerns of its primary partner and collaborator, the United States, which is understandably worried about its own security,” Marulanda told InSight Crime.

And while Brownfield’s argument that Colombia has insufficient funds for its crop substitution programs is probably justified, the United States could be doing far more to support this alternative initiative, according to Senior Associate at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) Adam Isacson.

“The [US government] is clearly unenthusiastic about Colombia’s crop substitution plan,” Isacson told InSight Crime.

Colombia’s two-sided and seemingly contradictory strategy is already causing problems in various areas. By eradicating swaths of coca fields by force while simultaneously convincing farmers to sign up for crop substitution programs, authorities have unsurprisingly sparked confusion and even violent protests in the countryside. Should the country heed US demands to increase forced eradication, this scenario will only be exacerbated.

SEE ALSO: Coverage of Drug Policy

Another underlying obstacle is that the United States has yet to remove the FARC from its list of terrorist organizations. Keeping this label will hinder US assistance to crucial elements of the peace deal that may be considered “material support to terrorists,” Isascon explained.

As well as preventing US support for the substitution programs, the FARC’s “terrorist” status may end up weakening economic assistance for reintegrating rebels.

“The question of ‘when does a terrorist stop being a terrorist’ remains really unresolved,” Isacson said, adding that the same issue hampered US support for Colombia’s notorious paramilitaries, the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia – AUC), after they demobilized in the mid-2000s. The AUC pact ultimately failed to reintegrate scores of demobilized combatants, many of whom are now operating in Colombia’s most powerful criminal organizations.

Furthermore, the US request that Colombia not rule out extradition of people involved in the peace accords is no small issue. The threat of possible extradition could cause some FARC leaders to reconsider their tepid support for the peace process. Recent months have already seen scores of guerrillas abandoning their camps and going rogue.

If the Colombian government acquiesces to US pressure for heavier-handed anti-drug policies, it risks undermining its promises to the demobilized rebels and coca farmers, threatening the viability of the historic peace deal. This scenario is already playing out in several vulnerable areas, with deadly consequences. But if Colombia disregards US demands, Marulanda argued, a “political confrontation” between the two nations remains a possibility.