Brazil’s most violent major city, the colonial metropolis of Salvador de Bahia on the country’s northern coast, has been hit by an influx of organized crime and drugs over the past five years, causing violence to rise as gangs battle for control of local markets.

Homicide rates in Brazil, home to more of the world’s most violent cities than any other nation, have remained fairly steady over the past decade overall. What has changed, however, is the location of these cities – while urban areas in southern states like Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo have seen a substantial drop in murders, homicides have jumped dramatically in the north.

Salvador, the capital city of the northeastern state of Bahia, has been one of the hardest hit by this migration of violence. With about 60 homicides for every 100,000 people, Salvador’s murder rate is more than double that of Rio de Janeiro’s capital, at 21.5 per 100,000, and four times that of Sao Paulo, at about 15 per 100,000.

Much of the success in Rio and Sao Paulo has been credited to security initiatives like the Police Pacification Units (Unidades de Polícia Pacificadora – UPP), which began in 2008, and gun control laws. Between 2002 and 2012, the murder rate dropped by almost 66 percent in Rio and 71 percent in Sao Paulo, while soaring 161 percent in Salvador, making it one of the most violent places in Brazil.

One explanation for this uptick in violence is that security gains in the south and a growing domestic crack cocaine market in the north pushed the First Capital Command (Primeiro Comando da Capital – PCC), Brazil’s premier criminal group, to expand its influence northwards. This has been a particularly intense phenomenon in Salvador, where the PCC’s alliance with a local gang is fueling a violent war over control of the city.

Salvador’s Gangs: the Peace Command, Caveira, and the PCC

Like most of Brazil’s criminal organizations, Salvador’s two main gangs, Comando de Paz (Peace Command) and Grupo de Perna, were born in Bahia’s prisons. These groups were initially founded to fight for improved prison conditions and inmates’ rights – and also to seek revenge for murders carried out by other inmates or prison staff. The Peace Command has since become Bahia’s biggest prison gang, and has controlled much of Salvador’s drug trade since 2008.

The Peace Command isn’t the only gang with an interest in Bahia’s local drug market. Grupo de Perna, known as “Caveira” (Skull) or “Caveirão” (Big Skull), has steadily gained power since the mid-2000s and is now allied with the Sao Paulo-based prison gang, the PCC, which is one of the most powerful criminal organizations in Brazil. These two groups have become so intertwined that Caveira has essentially become synonymous with the PCC in Bahia.

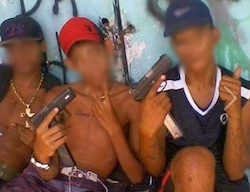

Caveira also goes by the name 1533, which represents the numerical order of the letters in the alphabet for PCC: P (15); C (3); C (3). Likewise, rival group the Peace Command is known as the 315. These numbers can be seen scrawled on walls in some of Salvador’s rougher neighborhoods. Although Caveira seems to have a stronger social media presence, both Caveira and the Peace Command use Facebook and other social media platforms to post photos displaying their weapons, claim neighborhoods and threaten one another.

These ongoing tensions between the Peace Command and PCC-Caveira alliance is one of the main causes violence in Salvador. While homicides subsided somewhat in the city in 2013 and 2014, according to official government numbers, local analysts say the conflict between these gangs flared up once again in 2014 and that a respite in the near future is unlikely.

Not helping things is Salvador’s growing local drug market, as Bahia’s capital has become “ever more segregated, divided and poorer in some areas,” according to Luiz Lourenço, a security expert and professor of sociology at the University of Bahia. He says the city’s criminal landscape “looks similar to Sao Paulo in the 1990s,” when murder rates in some neighborhoods skyrocketed to more than 110 per 100,000. Analysts have also attributed Salvador’s rising violence to an influx of firearms, income inequality, rampant corruption in the city’s government, and an influx of people moving to the city looking for work.

A map from 2013 indicated the Caveira controls eastern Salvador, while the Peace Command is based in the city’s western neighborhoods. But the two groups are engaged in a constant block-by-block battle for territorial control. “They mark the walls with CP [for the Peace Command’s initials] and PCC,” one resident told local newspaper Bocão News. “If I live in a street controlled by the CP I can’t go to the next street belonging to the PCC. We are living in terror and they’ve staked out the territory. We do not know where to turn.”

Caveira tends to be more business-minded and less violent, says Lourenço, who attributes this to Caveira’s ties with the PCC, which prefers to keep violence levels down in order to maintain a lower profile. However, as with the PCC, Caveira engages in calculated episodes of intense violence in order to intimidate other gangs and claim its territory.

Salvador’s police force has launched several community programs meant to combat the surge in killings, but the police are widely distrusted by city residents. To date, police efforts have yielded few results other than flooding the state’s penal system with alleged gang members.

Both the Peace Command and Caveira have been fueled and strengthened by Bahia’s surging prison population, which increased by 311 percent between 2000 and 2011. Although the state has built more prisons meant to accommodate the rising number of inmates, most of these are well over capacity. Increased incarceration rates have only spurred gang rivalries, as prisons have become hubs for recruiting new members, and also serve as the staging ground to plan criminal operations.

Salvador’s high violence rates aren’t just the result of organized crime — Lourenço also attributes the phenomenon to Brazil’s increasing “culture of violence,” pointing to the high number of murders over domestic disputes, problems with neighbors and other minor scuffles. Weak government institutions and widespread impunity for all sorts of crimes have perpetuated this culture, and has even spread into law enforcement bodies, Lourenço says.

Despite Salvador’s economic boom in recent years, problems like economic inequality, racial tensions, and unemployment persist, feeding crime and violence. As murder rates and drug use continue to climb in northern Brazil, it looks like those who live on the periphery of Bahia’s capital will likely remain vulnerable to the whims of the underworld.