For the second time, the Salvadoran embassy in Washington DC is about to turn into a temporal home for a police official linked to Jose Natividad Lena Pereira, alias “Chepe Luna,” an elusive drug trafficker, as confirmed by two former ministers and the head of an investigative team in San Salvador.

On April 30, the Salvadoran Chancery received notice from the National Civil Police that sub-commissioner Luis Ernesto Nuñez Carcarmo was named a police attaché in the El Salvador Embassy in Washington DC. Nuñez will earn $7,000 a month, more than the ambassador. Sources in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs confirm that the application has already gone through the Ministry of Finance, charged with approving the appointment and salary. From there on, Nuñez’s passport will be sent to the US Embassy in Santa Elena for the respective diplomatic visa.

In 2009, the police inspector general opened a file on Nuñez for “links with the renowned drug trafficker known as Chepe Luna.” Luna had repeatedly mocked Salvadoran authorities, as his police collaborators passed him information about the US-supported task force operations carried out between 2005 and 2006, in four separate failed attempts to capture him.

[Read InSight Crime’s coverage of Chepe Luna]

Nuñez is the second official with supposed links to Chepe Luna to be granted an important role in Washington. In 2006, commissioner Ricardo Menesses, then the director general of the police, was named a police attaché in the embassy, after President Antonio Saca ordered that he should quietly retire, according to a former member of Saca’s cabinet, who was directly involved in the Chepe Luna investigations.

“When all the operations to capture [Luna] failed, I went to see the president and I told him, ‘we’ve been embarrassed as a country.’ A few days later, the president told me that he was removing Menesses,” the ex-member of the cabinet said, who wished to remain anonymous in order to speak freely and avoid reprisals.

How these two police officials were assigned to El Salvador’s most important diplomatic headquarters – after being linked with such an important alleged drug trafficker – reveals the degree to which criminal groups have penetrated the agency.

For his part, Nuñez is an official with an extensive disciplinary record within the police force. Witnesses who testified before the Government Ethics Tribunal have even accused him of being involved in a coffee theft case.

Between 2004 and 2006, the Directorate General of Customs – one of the Salvadoran institutions to first follow the trail of Chepe Luna – profiled Nuñez as one of Luna’s collaborators, back when Luna was primarily dedicated to contraband and human trafficking. According to one investigator who worked on the Luna case and on the Perrones case between 2004 and 2009, investigators had to “twist the arm” of the Ministry of Finance (which oversees Customs) in order to get Nuñez transferred out of the police finances department, one of the police units most infiltrated by the drug trade.

At the end of 2004, the recently inaugurated administration of President Antonio Saca followed the US Embassy’s suggestion to create a special task force based out of the Security and Finance Ministries, in order to combat contraband and the trafficking of people and drugs in eastern El Salvador. This region is where a group of businessmen were steadily gaining power. They used legitimate companies in order to disguse the fortunes they gained from running contraband. And at the end of the 1990s, they began moving cocaine from Costa Rica to Guatemala, as well as some parts of the US East Coast.

[Read InSight Crime’s coverage of the Perrones]

The task force was advised by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI). Its first and foremost task was nabbing Chepe Luna, whom the US was tracking closely thanks to an international warrant that a New York court had issued for drug trafficking, and because Nicaragua intelligence had profiled Luna as one of the principal movers of undocumented migrants from Central America to the north.

One of the former Salvadoran ministers who led the task force and a Salvadoran chief of investigations who worked closely on the Luna case both agree that the attempts to capture the drug trafficker failed because “the highest levels of the police” leaked him information about the plans.

The investigator who worked on the task force explains that they profiled Nuñez as one of the men closest to Chepe Luna, “someone who would even get into cars with him.”

Previously, Romeo Melara Granilla, the police inspector general from 1999 to 2009, had opened files on the sub-commissioner for minor infractions. “They opened one file after another, but he was always protected,” explains an investigator from police intelligence.

In a separate case in 2007, two agents testified before the Government Ethics Tribunal – an autonomous government institution charged with handling accusations by citizens against public officials – that Nuñez had confirmed an order that they shouldn’t recuperate sacks of coffee that two landowners had reported as stolen. According to those who reported the crime, another landowner in the coffee zone in western El Salvador – a district which fell under Nuñez’s command during that time – was responsible for the robbery and had good relations with the police. So it says in file 66-TEG-2007, dated May 25, 2009. Thanks to this incident and other similar cases, the Salvadoran Coffee Council complained to the Ministry of Finance that Nuñez was “inoperative.”

It wasn’t until October 27, 2009 that police inspector general Zaira Navas, appointed by the Funes administration, opened a formal investigation into Nuñez and his “links to the drug trafficker Jose Natividad Luna Pereira,” according to Navas’ 2010 executive report. Witnesses cited in the investigation said that Nuñez destroyed documents that implicated Chepe Luna in various crimes.

When police director General Francisco Salinos was appointed in 2012, he named a former judge, Carlos Linares Ascencio, as inspector general on July 16, following Navas’ resignation. As head of the office, Linares’ first and so far only public action was to reject – without any legal explanation – the 20 files that Navas had opened against top ranking police officials, for infractions and crimes that ranged from collusion with drug trafficking to torture. President Funes stayed quiet, even though during the first two years of his administration, he had defended Navas in international forums and before his political opposition.

Asides from putting an end to the Nuñez investigation, the Salinas administration accommodated the sub-commissioner with a trip to Bogota to an exhibition of defense technology, according to the listing of official police trips in 2012. Nuñez was also given the responsibility of managing a fund worth some $75,000.

As a police attaché in Washington, Nuñez will earn $7,000 a month, according to the police manual that deals with police attachés in diplomatic headquarters abroad, which Salinas approved on March 1, 2013. According to that manual, there will be another two officials based in Washington, an adjunct-attache who will earn $6,000 and an administrative assistant who will earn $4,000.

When he starts his new job, sub-commissioner Nuñez will become the second alleged collaborator of Chepe Luna to take refuge in Suite 100, 1400 16th Street NW in the US capital, despite the investigations that two different presidential administrations opened against him regarding his links to Luna, and despite the subordinate officers who linked him to a criminal network dedicated to robbing coffee in western El Salvador.

The National Civil Police did not respond to InSight Crime’s requests for comment about Nuñez’s work history and his new assignment in Washington.

[See InSight Crime’s coverage of organized crime in El Salvador]

The Antecedent

For his part, strictly speaking Menesses never was a police attaché at the embassy – he was a deputy chief, a position designed by the Salvadoran diplomatic hierarchy for the middle command at the embassies. Nevertheless, due to his status as a police officer, Menesses was charged with revising and sending to El Salvador the lists of deportees with criminal records, a task that become fundamental after 2006, when the Bush administration executed the Secure Communities policy across the US, which, among other things, resulted in an important increase in friction and repatriations between Washington and El Salvador.

Nevertheless, Menesses’ record was better known than that of Nuñez. One memo by the police inspector’s office, dated September 24, 2010 – which Funes echoed before the United Nations General Assembly – says, “We initiated investigations into serious and very serious misdemeanors linked to the former director general, who was blamed for the supposed failure of four operations designed to capture renowned drug trafficker Jose Natividad Luna Pereira, due to the leakage of information when [Menesses] was director of the institution; protecting a person accused of homicide; illicit enrichment; among others.”

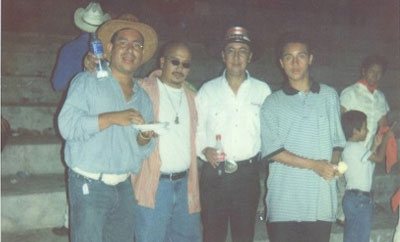

Recently in San Salvador, one of the investigators of the special task force that chased Luna in 2004 confirmed the link. “When the operations failed, the intelligence teams that tracked Luna on the ground showed us photos of Menesses on the farm that Chepe kept in Barrancones in those days, near the Fonseca Gulf, a cocaine transit zone.” These intel teams included an anti-drug trafficking unit, the GEAN, which was vetted by the DEA.

“Later on the Menesses case was too obvious. He began buying horses. He paid cash for a house worth more than $100,000,” the chief of the investigators said.

In 2009, the Chancery stripped Menesses of his diplomatic immunity when Inspector Navas made public the accusations that he was supposedly linked to Chepe Luna. Then came a newspaper’s publication of a photo of Menesses — previously an advocate for the government’s tough “Iron Fist” anti-gang policy — with Carlos Barahona, alias “Chino Tres Colas,” leader of the Barrio 18 gang. Following these incidents, Menesses left the police force in 2011.

It wasn’t the first time he’d made a silent exit. In December 2005, he’d quietly left his post as police director, before eventually heading to Washington. That time, there was no scandal. Antonio Saca had arrived to the presidency in 2004 promising greater transparency, among other things. The exit of his police director due to links to one of the Salvadoran drug traffickers most wanted by the US was brouhaha worth avoiding. The administration offered the commissioner diplomatic immunity, a job worth $4,700 a month, and an unspecified bonus. And thus Menesses left for Washington.

An old friendship

In contrast to Menesses, Nuñez comes to Washington as a formal police attaché: his position depends on El Salvador’s police and he will be governed by the manual signed by Salinas. Lists of deportees will also arrive at his desk, but he will also handle “Denuncia Express,” a transnational program for reporting extortion inaugurated in 2010 by the Funes administration.

In reality, these two Salvadoran police officials have plenty in common. Both resigned honorably from the military on May 12, 1994, and joined the recently created National Civil Police, via executive order 221. Both headed the much-questioned financial division of the police, the first to be infiltrated by the eastern contraband-runners who would later become the Perrones.

An investigator who still works in the Executive, and who led the investigations into the Perrones, summarizes the relationship between Menesses, Nuñez, and other officials as follows: “In 2004, when Menesses was director, [Oscar] Hernandez Aguilar [current head of police intelligence] was head of finances. The Finance Ministry was pressuring to remove him, because he was favoring Chepe Luna and the Perrones. Menesses [replaced Aguilar] with Nuñez, and everything went on as before. The mafia went on.”

One of these officials later ended up in Washington. The other one is just about to arrive.

Hector Silva Avalos is a Salvadoran journalist and current resident fellow at American University’s Center for Latin American and Latino Studies (CLALS), which sponsors InSight Crime’s work. He is writing a book about El Salvador’s police force.