The latest revelations about land trafficking in Peru show how unchecked urban sprawl can foster criminal enterprises that operate with official complicity.

In the early morning hours of May 25, Commander Humberto Santillán Otiniano and 22 members of his unit gathered outside the Rímac municipality’s Criminal Investigations Division headquarters (División de Investigación Criminal – Divincri) in the Lima province.

As chronicled by the television program Cuarto Poder, there Commander Santillán and his unit planned an early morning raid on on a property in a northern district known as Puente Piedra.

Upon arrival in Puente Piedra, Cuarto Poder says the officers met two members of the “Babys of Oquendo” (Los Babys de Oquendo) criminal group. The Babys used their official connections, firepower and bureaucratic contacts to steal and resell land.

That morning, the two Babys members put on police uniforms and bulletproof vests, then led the officers to a property where they planted a stolen vehicle and weapons and arrested several people. With the help of corrupt administrative officials who created false documentation, the Babys later became owners of the 17,000 square-meter terrain.

The May 25 operation was one example of how the Babys — via police and bureaucratic connections — worked in a half dozen municipalities in the northern part of Lima province to steal and resell land.

During a June 28 press conference, authorities said that 24 police officials — including three ranking officers — and three penitentiary officials were among the 61 arrested members of the Babys of Oquendo.

Interior Minister Carlos Basombrío Iglesias also said the group was the offspring of two dismantled criminal organizations named the “Injertos del Fundo Oquendo” and the “Destructors.”

Authorities claim all three groups were led by incarcerated Jacinto Valentín Aucayauri Bellido, alias “El Cholo Jacinto.” Following his death in prison in April 2017, his half-brother Juan Enrique Ramos Bellido, alias “Kike,” who was incarcerated in the same prison, took over, and began directing the group from his jail cell.

Authorities used intercepted phone calls between members inside and outside of prison to build the case and decipher its modus operandi, Cuarto Poder reported.

The leadership and members have survived the changes in the criminal organizations, and the Babys of Oquendo is more sophisticated than its predecessors, hiding its extortion activities behind a fake union and becoming less violent so as not to attract the attention of authorities.

InSight Crime Analysis

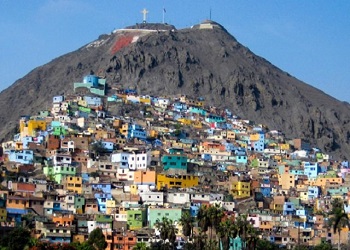

Puente Piedra is one of Lima province’s 43 municipalities. It is part of what has become Greater Lima, which is now Latin America’s sixth largest metropolitan area, with a population of nearly 10 million.

The municipality is littered with what Peruvians call “pueblos jovenes,” or “young towns,” a euphemism for shanty towns or slums. The areas have varying degrees of infrastructure, development and police and regulatory presence.

SEE ALSO: Peru News and Profile

The absence of the state offers groups like the Babys de Oquendo opportunity. Theft and resale of land is common in these pueblos jovenes. Just last month, authorities announced the dismantling of a similar group named “Los Injertos de Nuevo Ayacucho.” Like the Babys, this organization had been dedicated to land trafficking in northern Lima since the 1990s.

Land trafficking seems to rise with urbanization. Peru has urbanized faster than most countries in the region. Since 1980, Lima’s population has doubled. And since 1965, the percentage of the population living in urban areas has gone from 50 to 80 percent. (See World Bank graphic below)

Peru has been able to offset some of these growing pains with one of the most vibrant economies in the region. Since 2001, the country has had an average of 5.3 percent growth per year, according to World Bank data.

But the burgeoning Peruvian economy has not kept pace with the urbanization. The city hugs the coastline for nearly 200 kilometers, pueblos jovenes continue to spring up without constraint, and the informal economy thrives at all levels.

Some Peruvian scholars celebrate the uniqueness, resiliency and creativity of this urban migrant class, which has become a kind of “capitalist insurgency.” But the results, as the Babys de Oquendo and other criminal groups show, are far more chaotic and dangerous on the ground level.