El Salvador’s prison system is the headquarters of the country’s largest gangs. It is also where one of these gangs, the MS13, is fighting amongst itself for control of the organization.

*This article is the last in a five-part investigation, “The Prison Dilemma in the Americas,” analyzing how government mismanagement, neglect and corruption have made the jails in the region powerful incubators of organized crime . Download the full report or read the other chapters in this investigation here.

Salvadoran authorities believe the plan to kill Walter Antonio Carrillo Alfaro, alias “El Chory,” was hatched inside the Zacatecoluca jail sometime in late 2015. Chory — a mid-level leader of the Mara Salvatrucha (MS13) — was defying the group’s leaders. Therefore, they determined, he had to die.

The death sentence for Chory was part of a battle for the gang’s top positions. Chory had organized meetings to judge the MS13’s maximum commanders, the so-called “historical leadership” or “ranfla histórica,” who Chory and some of his fellow mid-level commanders believed were using the gang for their own financial gain, especially during an ill-fated truce the ranfla had negotiated with rival gangs and the government in the years prior.

The ranfla histórica had been disrespectful to the “barrio” — the gang’s nebulous term for its core ethos — Chory had said publicly from his jail cell in the municipality of Izalco on the other side of the country. It appeared that members of the ranfla had taken large sums of money from the country’s political parties — Chory believed it was as much as $25 million — as part of a quid pro quo to help the parties during the elections.

The ranfla histórica in Zacatecoluca was livid. Chory (pictured) and his cohorts looked ready to expose their hypocrisy during the truce. But they also threatened to tear apart the country’s largest, most formidable street gang. The MS13 had become a national security threat in El Salvador and part of the US government’s short-list of the region’s most dangerous and ambitious criminal groups. Chory endangered the ranfla’s hold on the group, and their dreams of taking the gang to the next criminal level.

The leaders knew the prison and the legal system well enough to put their plan to assassinate Chory into motion. And in November 2015, they figured out when one gang member from Zacatecoluca and one from Izalco, where Chory was housed, would appear in the courts in San Salvador for routine hearings at the same time. There, in the court holding area, the prisoner from Zacatecoluca passed a written message to the Izalco prisoner with the order to kill Chory.

Assassinating Chory would not be easy or cost-free. Chory was a well-respected and revered leader from a powerful faction of the MS13 known as the Fulton Locos Salvatruchas. He was 40 years old, and had earned his gang stripes in Los Angeles before being deported back to El Salvador. In the year prior, he had gotten most of his Fulton faction and more than a dozen other factions to join his mini-rebellion, and in Izalco he had four bodyguards with him at all times.

Chory was also preparing for battle. He had not just organized several meetings to talk about how to upend the ranfla histórica. He had displaced the MS13 leaders in Izalco, and he and several others had organized an attack on one of the ranfla’s car dealerships, burning several vehicles and causing thousands of dollars of damage. At some point, he started calling himself an “MS13 Revolutionary.”

Divide and Be Conquered

It was fitting that the power struggle within the MS13 would play out in the Salvadoran prisons. For the last decade, the penitentiary system in El Salvador has been the headquarters of the MS13 and the Barrio 18, the largest gangs in the country. The gangs’ takeover of the prisons resulted from a combination of bad public policy, and the gangs’ increasing organizational skill and guile.

The MS13 and its main rival, the Barrio 18, began arriving in the prisons of El Salvador around the time that the brutal civil war between the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional – FMLN) and the government was coming to an end. In the 1980s, political prisoners, most of them affiliated with the guerrilla group, had run the prisons with mixed results. In a preview of things to come with the MS13, two factions of the FMLN eventually turned on each other.

In 1991, as part of the peace process with the government that would transform the FMLN from a guerrilla movement into a powerful political party, most of the political prisoners were released. That same year, a young MS13 member wrote in a diary from his jail in San Francisco Gotera, the first references to the modern-day street gangs in the prisons. In the diary, the gang member spoke of how the National Guard tortured the prisoners, and of murders of inmates by other inmates.

With the political prisoners gone, traditional prison gangs took over the jails, the most emblematic of which was led by a man named Bruno Ventura, alias “Brother.” Brother did not come from the mafia or a street gang. He was imprisoned for armed assault on an appliance store. But with a dose of charisma and a selective use of violence, Brother and his armed gang, La Raza, took control of the country’s largest jail, La Mariona, and then much of the prison system.

“Bruno could be tough,” a former MS13 prison inmate told InSight Crime. “You couldn’t fuck around or go around advertising your gang. They would club you for that, but if you weren’t a problem, then Bruno didn’t give you any problems. He wanted the prisoners to live in peace.”

At the time, the MS13 and the Barrio 18 were not as strong as they are now. They were small, disorganized cells — or cliques, as they call them — and kidnappers and large-scale thieves dominated them inside the prisons. They were looked at like a leper colony; dirty, violent and drug addicts who had no self-control.

During Brother’s reign, inmates knew the limits, and he implemented a very effective system of control and internal punishment. They prohibited drug sales, killings, robberies, as well as assaulting other prisoners and visitors. There were also special rules for gangs: they were not allowed to show their tattoos or paint graffiti. Punishments included appointments with the “psychologist,” the euphemism used by the inmates for a wooden stick with which Bruno and La Raza would discipline anyone who had broken the rules.

But over time, Bruno’s power eroded, in part because the gang population increased. At the end of the war in El Salvador, the US government let Temporary Protected Status, which had allowed Salvadorans to remain in the US during the fighting, expire. The US also changed the laws regarding the deportation of ex-convicts. The two changes opened the door to mass deportations. Soon El Salvador was filled with former prisoners from the United States — over 81,000 ex-convicts were deported to El Salvador between 1998 and 2014, according to US government statistics — among them gang members from the MS13 and the Barrio 18, which had grown in the US during that time period.

El Salvador — and its neighbors Honduras and Guatemala — absorbed the deportees with great difficulty. In poor neighborhoods, MS13 and Barrio 18 cliques soon emerged. By the late 1990s, they had also become a significant portion of the prison population. The gangs were bitter enemies and clashed constantly inside the jails and juvenile detention centers. Violence among gang affiliated adolescents in youth facilities, most notably at San Francisco Gotera and Ciudad Barrios in 1999, led to the authorities assigning inmates to segregated prisons towards the end of 2000. The Centro de Internamiento de Menores de Tonacatepeque became a facility exclusively for the MS13 and El Espino for the Barrio 18. With this separation, the idea of segregation as an acceptable solution began to take hold and an air of inevitability set in.

The fighting even bothered Brother, who kept the MS13 and Barrio 18 mostly in check by remanding them to the “psychologist” every time there was a battle, as well as when more than four of them gathered in any one place for a “meeting.” However, when a judge transferred Brother from La Mariona to the San Francisco Gotera jail in December 2002, chaos ensued.

Like a grenade without a pin, the jail exploded. Shortly after Bruno’s departure, a contingent of prisoners attacked the anti-narcotics police who were doing a sweep, and using homemade knives, they killed them, as well as their drug-sniffing dogs. It was a sign that La Mariona had changed forever. Fighting amongst prisoners also became more intense and frequent.

Eventually, in an act of desperation, the general population asked the director of La Mariona to remove one of the two gangs, and the director put it to a vote. The MS13 lost; the director transferred MS13 members to Ciudad Barrios, a site that had previously housed only minors, thus beginning a de-facto policy of separating the gangs inside the adult penitentiary system.

With the transfer, the prison was divided into two between the Barrio 18 area and that of La Raza, Brother’s former armed wing. Soon, a battle for control erupted. The Barrio 18 were abused daily. They were fed the worst food and placed in the worst part of the jail. The ire of the “Cholos,” as they are referred to throughout the region, rose with every transgression. La Raza meanwhile, under their new leader José “Viejo” Posada Reyes, were biding time, waiting for their moment to attack the gang.

But the gang also had a plan. The Barrio 18 prisoners had obtained weapons from visitors, among them a grenade. And on August 18, 2004, that grenade exploded, announcing the gang’s frontal assault. On that day, they were hunters more than prisoners, and Posada’s men were not ready. Even though they had far more members, La Raza suffered huge casualties: 24 of the 34 killed were from Posada’s mini-army; dozens more were injured. If Posada himself hadn’t had a pistol, he would have been killed as well.

A few days later, authorities transferred 1,000 prisoners: 400 were classified as Barrio 18 members, and another 600 were classified as “sympathizers.” Some of them were transferred to Apanteos prison, where the fighting would resume three years later when the gang members found several survivors of La Raza. That fighting left 21 more dead. The other group was sent to the Cojutepeque jail.

That is how the gangs — at the end of their makeshift knives — won their segregation from the “civilian” prisoners.

There was no vocal opposition to the move to segregate, and the growing strength of the gangs in the prison system and the potential for explosive violence it represented gave authorities all the justification they needed. Quezaltepeque and Ciudad Barrios prisons became exclusively for MS13 prisoners, while Chalatenango and Cojutepeque were designated as Barrio 18 prisons. Sonsonate prison was reserved for “Pesetas,” or retired gang members. In 2006, there was a switch of designation between Chalatenango and Quezaltepeque, while the booming prison population saw sectors of the San Francisco Gotera and Apanteos turned over to the MS13, and the following year the newly constructed Izalco handed to Barrio 18.

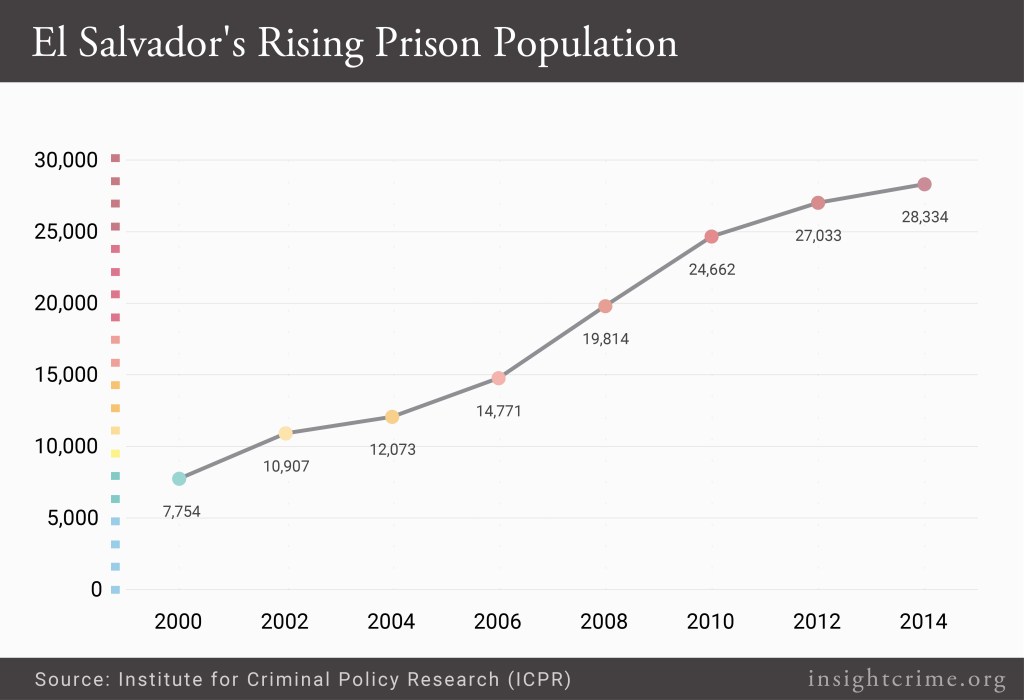

Government policy on the outside accelerated gang control on the inside even further. With the adoption of “Mano Dura” in 2004 — which was eventually annulled by the Constitutional Court — and later, “Super Mano Dura,” which remained in force, the police had the power to stop, search, and detain suspected gang members for simple things such as a tattoo or an alleged association. The prison population swelled. In 2000, the prisons of El Salvador had 7,754 prisoners; in October 2016, it had 35,879.

The separation of the gangs into their own prisons reduced violence, but it also granted them de-facto control of the penitentiary system. The leaders were safe from their enemies in prison, giving them the time and the space to restore command and control, and establish the rules and regulations within the gang. As Benjamin Lessing wrote in a recent Brookings report (pdf), the move gave the gangs a headquarters from which to recruit, and to expand their influence.

“It puts weakly or un-affiliated first-time offenders under gang custody and tutelage,” Lessing said in reference to the policy of separating the gangs. “Perhaps more importantly, it brings a broad range of street-level actors — anyone who might be sent to a given gang’s wing if incarcerated — under that gang’s ‘coercive jurisdiction.’”

They could also increase money-making opportunities, as a way to offset higher legal fees and to fulfill the need to support their families on the outside. The changes resulted in more systematic extortion of bus and taxi cooperatives, propane gas and other distribution services, local shops, as well as a number of other objectives. The impact was immediate and profound. The National Public Security Academy (ANSP) estimated that extortion increased 1,402 percent between 2003 and 2009. This money created a food chain that included gang leaders, their cliques, and their families, as well as police, guards and administrators in the prison system. In other words, because of the segregation in the penitentiaries, the gangs were able to systematize this criminal activity.

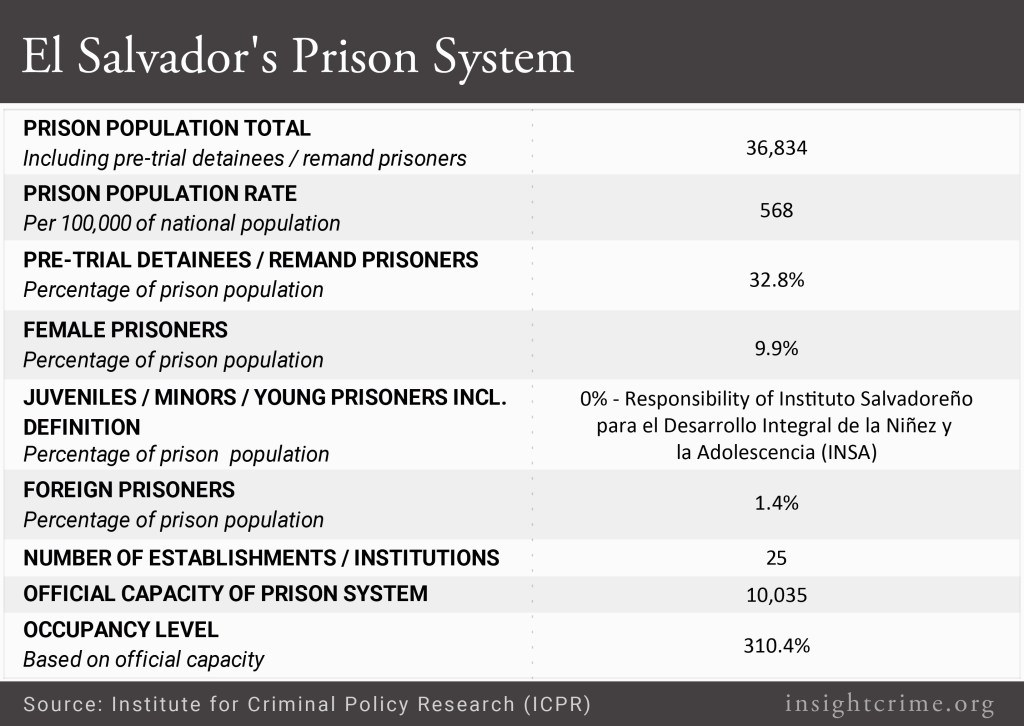

With mass incarceration, the prisons became central to gang members’ lives and their ethos. By 2015, of all the prisoners in the Salvadoran penitentiaries, a third were gang members, according to a study by the University of Central America “José Simeón Cañas” (UCA) and the Institute of Public Opinion (IUDOP) (pdf). From now on, gangs, and not political prisoners or petty criminals, would control the prison system in El Salvador.

Organizing from the Inside-out

The prisons serve the gang members in various ways. For the leaders of the gang, the prisons are a place from which they can continue their criminal operations, be relatively safe from attack, and expand their own financial portfolio via new contacts and opportunities. For the rank and file, going to jail is a rite of passage and a means of moving up the gang ladder. The shared suffering that comes from being inside the prisons provides cohesion and solidarity. It also provides a point of departure for contact with the outside, community and religious groups, who rightfully see and regularly denounce the deplorable conditions inside the jails.

InSight Crime researchers could not enter the jails during this research project due to government restrictions, but Martínez spent several months in 2011 in Ciudad Barrios where the MS13 holds sway as part of a study he published with Luis Enrique Amaya in the Francisco Gavidia University’s yearly investigative series (pdf); InSight Crime visited the Cojutepeque prison in 2012, where the Barrio 18 was in control. (See video below) It has since been closed. The prisons have many shared problems. In both the Cojutepeque and the Ciudad Barrios prisons, the prisoners sleep in small rooms where they string hammocks and other makeshift bedding one above the other. Cells made for 10 have as many as 50 prisoners. And there are problems with ventilation and light. One former prisoner said several other inmates went crazy due to the tight confines and the lack of light.

Health care services are nearly non-existent, and gang members are often sent to public hospitals in the last stages of dehydration, anaemia or delirium. They receive food almost exclusively from outside of the prison. They spend most of their time in dirt-covered recreational areas where they play sports or just mingle. There is a small arts and craft room in each facility but neither jail had job training programs or regular contact with psychologists.

Our observations coincide with what experts have written about the conditions in the jails. After visiting prisons in 2010, the Inter American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) chronicled (pdf), among other things, how inadequate waste disposal led to disease; how the inmates were forced to use their hands to eat; how lighting and ventilation were inadequate. A 2011 State Department report (pdf) and a recent report by El Salvador’s Human Rights Ombudsman echoed these findings.

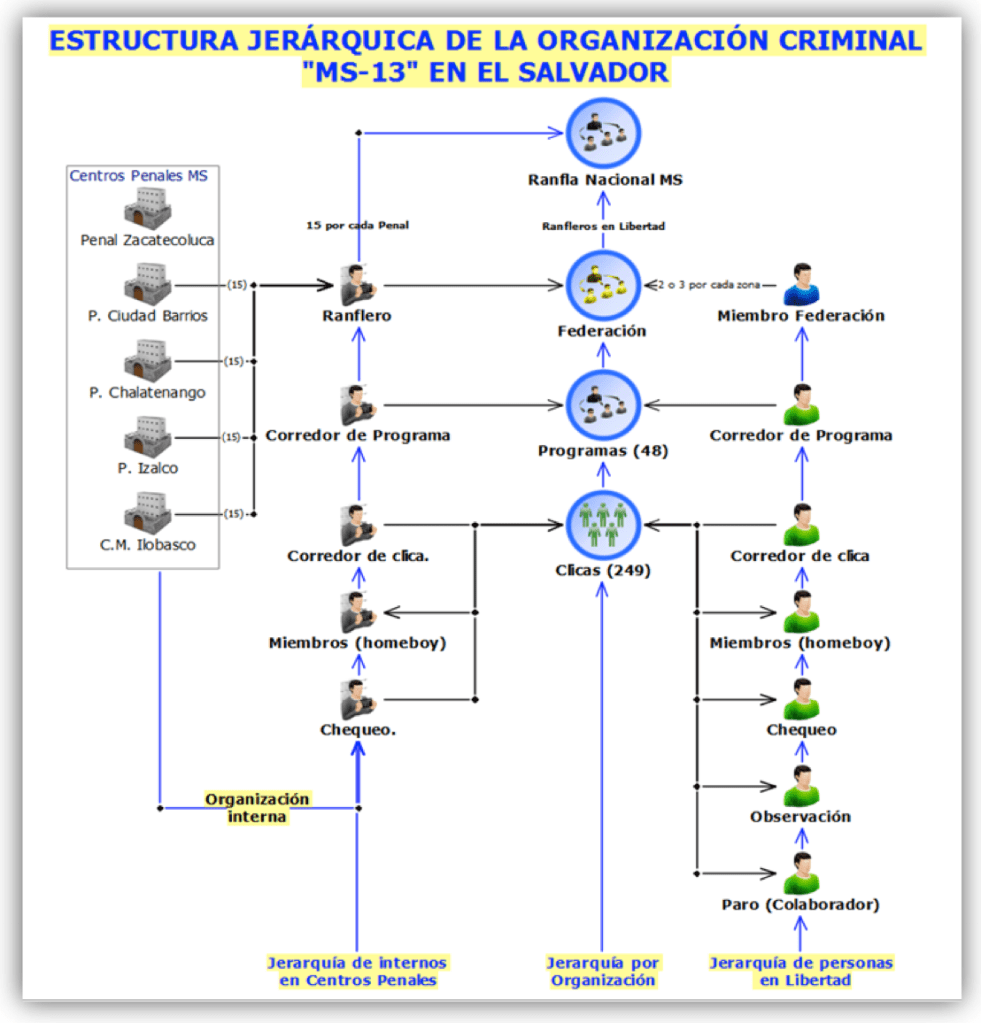

Gang leaders have turned these deplorable conditions into an advantage, using them to exert control over the other gang members. Survival requires discipline and a clear chain of command. Inside the prisons, for example, the MS13 has set up a strict hierarchy, according to a recent Attorney General’s Office indictment of the group. Each prison has a ranfla, a council made up of 15 gang leaders referred to as “ranfleros.” Below the “ranfleros” are lieutenants, which the gangs call “corredores.” Each of the “corredores” is part of a program, which control a number of cells, or cliques (“clicas”). In total, the MS13 has 48 programs and 249 cliques, according to the Attorney General’s Office indictment. The cliques also have corredores, who are responsible for their individual clique. Below them are members (“homeboys”), and below them, lookouts (“chequos”).

The gangs have also clear rules. Any transgression can be met with severe punishment, which the MS13 refers to as “descuento,” “corte” or “pateada.” According to Martínez and Amaya, the three most typical transgressions that lead to punishment are: 1) “disrespecting” the gang, an amorphous terminology that allows for various interpretations regarding the gang’s central purpose and guidelines; 2) disrespecting a wife, a girlfriend or a visitor; 3) stealing from a fellow gang member or thieving from the gang for one’s personal use or gratification.

The strict hierarchy and discipline system allow for the ranfla to control the flow of information and resources coming from the outside, which gives them incredible power over their membership on the inside. These resources, Martínez and Amaya say, are both legal and illegal. Among the legal resources are things as simple as water, food, clothes, money and visitation rights. While water takes on outsized importance because of the altitude at Ciudad Barrios, the visits are important in every prison. In addition to being emotional lifelines for these prisoners, visits are key ways to move contraband and money. They are also status symbols, and they can help with communication to the outside world.

Among the illegal goods are drugs, liquor, weapons, and telephones, Martínez and Amaya write. Of these, cellular phones might be the most important. They are both currency to be traded and sold, and critical tools that facilitate criminal activities inside and outside of the prison system.

The phones are also a key way of communicating amongst the gang, which helps keep some sense of cohesion in the group. The gangs have regular conference calls between the ranfleros and corredores in the prisons and with the leaders on the outside. These meetings help shore up divisions, provide internal discipline and determine strategies; they also help divvy up resources, and are the last word on whether many homicides go forward or not. In short, telephones are the glue that holds this sometimes shaky hierarchy together. Nearly every major, and many minor, decisions have to go through the leadership structures in the jail. This wouldn’t be possible without telephones.

SEE ALSO: Reign of the Kaibil: Guatemala’s Prisons Under Byron Lima

As in other parts of the region, the gang’s control over the whole organization from inside the penitentiary system stems from the inevitability of jail for this population. There is, quite simply, no escape from the prison system. Sooner or later, everyone in the gang or people they know will pass through the various parts of the system, be it the juvenile detention centers, the temporary holding facilities or the jails themselves. And if they have committed any transgressions, these gang members will face the consequences most clearly in jail.

Fleeing the gang does little to alleviate these possible consequences. The gangs have regional reach and an increasingly sophisticated intelligence-gathering system that encourages members to police their own. Gang members can also seek retribution via a family member or other close connections on the inside or the outside. Whether they are free or in jail, gang members are trapped into following the ranflas’ orders from the prisons.

Within the MS13, there is also a hierarchy of prisons. Martínez and Amaya say that in 2011, the highest level ranfleros were in the Zacatecoluca prison. “Zacatraz,” as it is popularly known, is the maximum security prison where there is much more control over the contact between inmates, and there is near constant supervision at recess times and during visits. San Francisco Gotera held a considerable number of high level members as well, while Ciudad Barrios, the so-called “Home of the MS13,” corralled members from every clique in the country.

After the government made Zacatraz the main holding facility for the ranfleros, the game changed. With less access to telephones and visitors, and increased vigilance by the authorities, ranflas held in Zacatraz began to lose control of their middle managers and their younger and more active recruits on the streets. In addition, they did not like the rules, especially around visits with their family and conjugal time with their wives and lovers. With time, the money also slowed to a trickle, and the ranflas’ power over the rest of the organization began to slip.

The conditions in Zacatraz, as well as the fact that the major gang leaders also had shared confines, led to talks between the ranflas of the MS13 and the Barrio 18, who became desperate to get out of the maximum security jail. Soon they brought in parts of civil society, churches and eventually representatives of the government. Their discourse was largely political and social in nature. The talks centered on lowering the violence between the gangs, which had reached epidemic proportions, improving conditions in the prisons, and providing the homeboys with more educational and economic opportunities. In this way, the truce was born.

The Truce

Peace processes, truces and other negotiations with criminal organizations frequently begin in jails. There is a practical reason for this: criminal leaders are often in jail. The nature of confinement also lends itself to dialogue and reconciliation. The impetus from the criminal side can be noble and practical. Criminal leaders get older and from jail often gain a perspective they did not have on the street. They also have families, and, whether they are in jail or not, they very often want to have regular contact with that family. But negotiations can also be nefarious, a form of subterfuge, a bald-faced effort to gain more power or to expand their criminal activities.

The gang truce in El Salvador combined both the nefarious and the noble. It was more violence interruption than actual truce — an intricate scheme involving the security ministry, police, prison officials, mediators, parts of the Catholic Church and the Organization of American States (OAS), which was designed to break the chains of retribution that have played out for years between the gangs. Some of this tit-for-tat is related to controlling territory where the MS13 and the Barrio 18 factions can sell drugs and extort money. But much of it is simply inertia, a product of decades of fighting, which has become an integral part of the gangs’ ethos since at least the early 1990s.

For a time, the truce did interrupt violence. Homicide rates dropped precipitously when the government moved fourteen gang leaders from Zacatecoluca prison to other prisons in March 2012, marking the beginning of the truce. There, the gang leaders could reaffirm their control over mid-level leaders who had asserted themselves while the ranfla histórica was in Zacatraz. The order went out to the street as well: homicides were to stop, or at least be greatly curtailed, and the ranfla was back in power. Negotiating the murder rate would become the gangs’ macabre leverage in their negotiations with government representatives, which were led by an ex-guerrilla named Raúl Mijango and the Salvadoran Catholic Bishop Fabio Colindres.

What else the gang leaders got in return is still something of a mystery, and it has become a point of contention amongst the gangs and a criminal case for the current government. In May, the Attorney General’s Office arrested several officials that facilitated talks, prison transfers and other logistical elements of the negotiations, arguing they illegally moved prisoners, opened their doors for illegal meetings and illegally paid money to the negotiators and benefits to the gang leaders. The most prominent official to be ensnared in the case is current Defense Minister David Munguia Payes, who, as the then-Minister of Security and Justice, was the architect of the truce along with Mijango. The Attorney General’s Office says that as much as $2 million of government funds were used unlawfully, part of it going to gang leaders for fast food, cable television, video games and exotic dancers for the gangs.

SEE ALSO: Where Chaos Reigns: Inside the San Pedro Sula Prison

Just how much the ranfla directly benefited from the truce is not known. Stories vary from flat screen television sets for their families to up to $30,000 per month for their participation. No evidence has emerged to establish the latter figure, but several people that worked with the truce said that money was deposited into the top gang leaders’ accounts. This money, according to these sources, did not trickle down to the mid-level leaders, much less to the rank and file, who at some point began wondering what they were getting from the high-level talks and prison transfers of their leaders.

The ranfla histórica also used the truce to reorganize its forces. Inside the jail system, there was a clear hierarchy that flowed from wherever the ranfla negotiating the truce was housed downward to the other jails. Outside, the MS13 created four major blocs from east to west, and grouped the programs and cliques under those umbrellas as means of facilitating communication to the ranfla histórica. The reorganization seemed to obey a business or war mentality. Indeed, the blocs made the MS13 look more like their guerrilla forbearers in FMLN than a group of street thugs.

With the truce, the ranfla histórica reasserted itself. The MS13 leaders from Zacatecoluca were moved to Ciudad Barrios and to make room for them, other leaders were transferred to San Francisco Gotera prison. It was a clear message to the mid-level leaders that ranfla was in charge again. Three flat screens arrived in Ciudad Barrios, so the MS13 members still housed there could watch everything from cartoons to the Spanish Soccer League. The ranfla in Ciudad Barrios also flaunted the power that came with the truce by regularly ordering food from Pollo Campero from their handlers and having it delivered to the prison. Parties followed, sometimes with prostitutes who pole-danced for the gangs.

The contrast within the penal system was stark. San Francisco Gotera became like an attic where the gang sent its dissidents and hoped that distance and isolation would drown out their rising voices. Ciudad Barrios, meanwhile, was like the presidential palace, where important meetings and diplomatic gatherings happened. In Ciudad Barrios, gang members received Miguel Insulza, the Secretary General of the OAS, and they had mass administered by Luigi Pezzuto, the Vatican’s representative in El Salvador. In San Francisco Gotera, the MS13 had to settle for a few new television sets and PlayStations, which would later be confiscated and destroyed by the police. On one side of the country, a gang celebrated its triumph, and on the other side, a gang waited for its moment.

Disrespecting the Barrio

The rumblings began not long after the initial movement of prisoners between Zacatecoluca, Ciudad Barrios and San Francisco Gotera. Meetings followed. Walter Antonio Carrillo Alfaro, the Fulton leader who would go on to be a key insurgent within the MS13, was in San Francisco Gotera and participated in those meetings.

Known as “El Chory,” a bastardized version of “Shorty,” Carrillo Alfaro was an old school gangbanger. He entered the MS13 as a 14-year old kid in the 1990s in Los Angeles, and had dedicated his life to the gang.

More recently, Chory was a leader in the Fulton Locos Salvatrucha, a “high class” clique in the MS13. In contrast to many other cells that came from downtown Los Angeles, the Fulton was formed in the San Fernando Valley, and they have a different past than the other cliques. Whereas the others were made up of poor kids, the Fulton was part of the original “Low Riders,” who later became small time drug traffickers and collected quotas from other petty dealers. They never went through the “Stoner” or Satan-worshipping period that the other, less evolved cliques went through when the gang first got its start in the 1980s.

The discussions that Chory took part in revolved around whether the ranfla histórica was disrespecting the “barrio.” Barrio, roughly translated, means neighborhood. However, for the gang, it is so much more. It is its core ethos, the means around which it organizes itself and its members. Barrio is about giving yourself to the gang. There is nothing that is above the barrio, because the barrio is the gang. When the ranfla started benefiting directly from the truce without including the rest of the gang, they were disrespecting the barrio. And when the ranfla started to use the gang for their own, personal business interests, they were disrespecting the barrio.

The ranfla histórica dealt with this discontent harshly, reportedly reprimanding more than a few mid-level MS13 members. Ironically, their argument was the same: these mid-level leaders were disrespecting the barrio. Over time, however, the ranfla’s ability to keep their mid-level leaders in line waned. And when the truce unraveled at the end of 2013, it became impossible. The result has been nothing short of catastrophic for a country still struggling with a legacy of internal conflict. Violence surged to make El Salvador the most homicidal nation on the planet that is not at war.

This is, in part, because that violence began to happen on multiple levels and in multiple settings, including in the country’s jails. There was fighting between and amongst the gangs. And there was fighting between the security forces and the gangs. El Salvador began to look like a country at war again. Between January 2015 and August 2016, 90 members of the police were killed; and 24 members of the armed forces, El Faro reported. During the same period, the police killed 694 suspected gang members, El Faro said, and have a virtual green light to shoot to kill at the slightest provocation.

The violence took its toll on the MS13. The frontline soldiers and mid-level commanders in the MS13 absorbed the brunt of rivals’ and police efforts to unseat them from their territory, and the ranfla’s “disrespect” of the barrio became that much more real for those on the street. Those rank and file are mostly Salvadorans who have never stepped foot in the United States and have to live with the $15 per day they get for food. Their disdain for the leadership stems, in part, from their belief that they are treated like second-class citizens, who have to cross a much higher threshold than their forebears in order to gain status in the gang, including a blood-filled initiation period.

By and large, the ranfla histórica of the MS13 in El Salvador come from the United States. And many of them simply stepped into their role as leaders due in large part to their deportee status. The most prominent among them is Borromeo Enrique Henríquez Solórzano, alias “El Diablito de Hollywood.” (pictured) Hollywood is a reference to his program, but Diablito is the presumed leader of the entire MS13 in El Salvador. The ranfla histórica is often referred to as “Diablito,” the “Little Devil,” and his 12 apostles.

El Diablito’s rivalries both inside and outside of the gang, as well as his ambitious criminal and political agenda, have stretched the gang to its breaking point, Salvadoran and US authorities say. He has been connected to attempts to increase the MS13’s footprint in the international drug market, as well as some of the ranfla’s car dealerships, the proceeds from which go to the individual gang leaders. El Diablito also negotiated deals with political parties in the country to receive cash for votes, investigators say. That money purportedly was shared amongst the leaders, not the rank and file, another affront to the barrio.

The bloody war in the streets, the one-sided split of the spoils from the truce and the haphazard application of the rules of the barrio moved leaders like Chory to hold more meetings. The rebellion was taking hold.

‘If you abide in my word, you are my true disciples’

Chory would not have normally been in Izalco. For years, the prison was reserved for the Barrio 18. When the Barrio 18 split in 2009, Izalco was divided between the Revolutionaries and the Sureños factions of the gang. Chory, along with dozens of his fellow MS13 members were transferred there in 2015, in part of an effort to reverse the course of action taken in the early 2000s to divide the gangs into their own penitentiaries. It was an implicit recognition that the strategy of separating the gangs had failed.

Chory’s transfer allowed him to spread his rebellion, which had gained momentum following the end of the truce and the tremendous spike in violence. The ranfla histórica was also transferred back to Zacatraz in January 2015, where its efforts to flex its muscles showed just how fragile its hold on the MS13 was. When several prominent ranfla histórica members like El Diablito tried to organize a hunger strike to force another truce on the government, their cohorts at Zacatraz refused to participate, according to law enforcement sources. Some leaders who had remained in Zacatraz even stopped talking to those who had negotiated the truce. Threats were lobbed, and authorities isolated several ranfla leaders, including El Diablito.

The insurrection was hitting its stride. When other ranfleros who had supported the truce were transferred to Izalco in early 2015, Chory called a meeting, according to a Salvadoran intelligence report obtained by InSight Crime, during which he ousted the leaders for not following the rebels’ mantra: “the gang does not sell itself or surrender.”

Chory and other leaders also mobilized several cliques and programs, among them the Sancocos, one of the most storied programs in El Salvador, to join the rebellion. Messages known as “wilas” (or “kites”) were passed, and the group began openly calling for “judgement” of the ranfla in Zacatecoluca for disrespecting the barrio. Some of them were also calling for a united front with the other rival gangs, a re-imagining of the gang frontiers that stemmed from the various gangs’ shared origins in Los Angeles and their allegiance to a powerful prison gang in the United States called the Mexican Mafia.

In July 2015, Chory and his cohorts declared themselves a new ranfla. According to an Attorney General’s Office indictment against several members of the gang, he also started referring to himself as an “MS Revolutionary.” During the same month, authorities intercepted a wila coming from Izalco to the gang members on the street. The message was from some mid-level leaders of the gang like Chory and called for more meetings, this time amongst those on the streets, where they called for an overthrow of the historic leadership. At its apex, as many as 13 other programs eventually pledged their support to the Fulton and Chory, according to an Attorney General’s Office investigation of the gang.

By then, the ranfla histórica in Zacatecoluca knew what was happening with Chory and other mid-level MS13 leaders and sought to deal with it. The leadership is still very powerful. It has the loyalty of the majority of the cliques and, even from jail, is feared by the majority of the gang members. They sent their own messages to the mid-level leaders. Some of them were conciliatory. Others were menacing. One message went from Diablito directly to Chory, allegedly via an evangelical pastor who thought he was facilitating a possible reopening of talks for a truce. The message was for Chory to consult the biblical passage John 8:31: “If you abide in my word, you are my true disciples.”

The Diablito had spoken, and with his word came that of the historic leadership, but Chory did not heed the warning. The insurrection continued, and in November, the fatal wila, calling for the attack on Chory in Izalco, was passed between prisoners at the courthouse and landed in Izalco. In addition to Chory, the wila called for the disciplining of some 70 other members of the Fulton program. Salvadoran intelligence also said it called for more direct attacks on security forces and their relatives as a means to force another truce.

But Chory and cohorts would not be cowed. In December, he and several others conspired to have their soldiers on the street burn several cars at a dealership controlled by El Diablito’s top lieutenant, Marvin Adilly Quintanilla Ramos, alias “Piwa.” Piwa is a young gang member from a small clique called the Criminal Gangster in Ilopango, in the department of San Salvador. In a relatively short time period, he had risen to become El Diablito’s top lieutenant in the street.

Like El Diablito, Piwa is a cunning operator who, in addition to helping the ranfla, was building his own political and economic empire from his government post in the city hall of Ilopango. Indeed, Piwa is at the center of the political storm about what ranfleros had received in return for their assistance during presidential elections and thereafter. Piwa, the Attorney General’s Office indictment of him and numerous others says, was getting $400 per month from the Ilopango mayor’s office.

Piwa’s duplicity is illustrative of why many distrust the gangs: at the same time he was receiving this salary from the government, he was also allegedly collecting money from each of the cliques to buy weapons from Mexico; and he was facilitating the training of two members of each clique to be part of the Special Shock Unit (“Grupo Elites de Choque”) of the gang, according to the Attorney General’s Office indictment.

Piwa, the indictment says, was also the one who gave the “green light” to kill Chory “for coming up with the idea of purging the historic leadership of the MS and for saying the leaders had taken money for the truce for themselves,” the indictment says.

That plan had to rely on speed and overwhelming force. And so at 1 pm on January 6, 2016, armed with machetes and makeshift knives, the ambushing party took Chory and his bodyguards by surprise. Prison authorities said it took but a few minutes to corral and then hack Chory and two of his bodyguards to death. One bodyguard survived, but with serious injuries.

The End of the MS Revolutionaries?

After Chory and his two bodyguards were killed, prison officials put Izalco and several other jails on lockdown and isolated as many as 80 imprisoned members of the Fulton from their counterparts. But another message had been sent: the ranfla histórica still had the power and the reach to kill highly respected leaders like Chory. Several other members of the Fulton later paid Piwa over $40,000 for the cars they had destroyed on his lot, the Attorney General’s Office indictment says.

But the retributions had already begun. On January 25, Chory’s girlfriend was killed. On January 28, Marvín Osmín Roble, another Fulton, was killed in Ciudad Barrios prison.

Inside and outside of the prisons, several remaining members of the rebellion were also killed or disciplined, the Attorney General’s Office indictment says. Corredores who had supported the rebellion were demoted. El Diablito’s orders were clear: “Remove all those who were close to or had something to do with the possible attack,” he told one of his operators.

SEE ALSO: Colombia’s Mirror: War and Drug Trafficking in the Prison System

Recriminations and conspiring against the Fulton program have continued for months. But it’s not the clear the rebellion has completely ended. Several videos about the gangs’ talks with political leaders from the two major parties have since revived questions about the quid pro quo between the gang leaders and the politicians, and possible payments that were never shared with the gang’s mid-level leaders and rank and file members. The government is also pushing ahead with cases against MS13 leaders such as Piwa.

Meanwhile, there is still unrest in Fulton. “That is not over. Chory was a monster, but he was our monster,” a member of the Fulton told InSight Crime.

On January 22, just a little over a year after Chory’s assassination, three members of Fulton killed Juan Carlos Hernández, a leader of the Hollywood clique and a prisoner in Zacatecoluca, with some makeshift knives, a sign that the battles will most likely continue, and the front lines will remain the same: in El Salvador’s prisons.

*Steven Dudley is co-director of InSight Crime. Juan José Martínez d’Aubuisson is a Salvador-based anthropologist. James Bargent also assisted in this investigation. Top photo by Manu Brabo, Associated Press.