The hunt for the leadership of the Urabeños, Colombia’s most powerful criminal group, has now been ongoing for over half a year. With many labelling the campaign a failure, federal judicial officials in Colombia have defended the operation saying it has allowed authorities to better understand the previously unknown internal operations of the criminal organization they have dubbed the “Clan Usuga.”

“By 2018, the Gaitanist Self-Defense Forces of Colombia will be an armed political actor looking to negotiate with the national government,” stated the document discovered by police at an Urabeños training school named after fallen leader Juan de Dios Usuga, located in the forests of Ungia in the state of Choco.

The site was just one of a network of training schools that federal authorities have dismantled as part of Operation Agamemnon, a campaign that has seen the security forces spend seven months searching the mountains, rivers and jungles of the region of Uraba in the northern departments of Antioquia and Choco to capture Dairo Antonio Usuga, alias “Otoniel,” the head of the Gaitanistas, better known as Clan Usuga or the Urabeños.

This article originaly appeared in Verdad Abierta and was translated and reproduced with permission. See original article here.

As a result of the operation, police have not only captured members of the Clan Usuga, but also uncovered significant amounts of organizational material including internal statutes, combat manuals, and discipline records. Police have also seized electronic equipment containing vital information about the operations and organizational structure of the group.

Because of this recovered material, authorities defend Operation Agamemnon as a success. However, the critics claim otherwise, pointing out the operation has yet to capture the head of the “Gaitanists” or any of his top lieutenants despite the deployment of more than 1200 police officers, 1000 members of the military, and a fleet of artillery helicopters — a mobilization only comparable to the famous “search bloc” that hunted down the now-dead Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar.

“If it weren’t for Operation Agamemnon we would not have the information that has allowed us to become much more familiar with the operational structure of the Clan Usuga,” says Natalia Rendon, the specialist organized crime prosecutor tasked with leading the effort to prosecute members of Clan Usuga. Rendon considers it inappropriate to measure the success of an operation like this solely on the capture of a kingpin like “Otoniel.”

“We don’t achieve anything by capturing him if we don’t dismantle the entire structure.” she said. “Today we have a much clearer idea of who and what makes up [Clan Usuga], and that is really important.”

From “Castaño’s Heroes” to the “Gaitanistas”

One thing the authorities now have clear, is that the origins of the Urabeños dates back to 2006, when Vincente Castaño Gil, chief spokesperson for the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), disobeyed the national government’s demands for Castaño and 14 other paramilitary leaders to confine themselves in a recreational center in La Ceja, Antioquia as part of demobilization negotiations.

In that moment, Castaño Gil asked a handful of his closest allies not to turn themselves in because, he said, the AUC had been duped. Among those that followed Castaño was Daniel Rendon Herrera, alias “Don Mario,” who returned to the municipality of San Pedro de Uraba to oversee the drug trafficking business previously run by the AUC’s Elmer Cardenas Bloc headed by his brother Fredy Rendon, alias “El Aleman.”

As organizations such as the International Crisis Group and the Peace Process Support Mission from the Organization of American States noted at the time, “Don Mario” drafted a large number of former AUC combatants. Among them were several fighters that shared a past as former members of the guerrilla group the Popular Liberation Army (EPL): the Usuga David brothers, Roberto Vargas, alias “Marcos Gavilan,” and Francisco Morela, alias “Negro Sarley.”

Out of this “Castaño’s Heroes” were born. Castaño was murdered by AUC commanders that objected to his stance in 2007, but the group continued to grow gradually under the leadership of Don Mario and in 2008 announced itself to the nation under the name the Gaitanist Self-Defense Forces of Colombia by shutting down Uraba in an “armed strike” in retaliation for what they called the “national government’s failure to uphold the agreements that they had settled on with the AUC.”

But neither the capture of “Don Mario” on April 16, 2009 in a rural zone of the Uraban municipality of Necocli, nor the death of his successor, Juan de Dios Usuga, alias “Giovany,” on December 31, 2011 in nearby rural Acandi signaled the death of the organization. Instead, the Gaitanistas demonstrated their power in January 2012 when they were able to paralyze more than 150 municipalities in 4 departments in another armed strike in retaliation for Giovany’s death.

SEE ALSO: The Victory of the Urabeños – The New Face of Colombian Organized Crime

“At that moment they had 17 fronts in Cordoba (Moneria-Montelibano-Tierralta), Uraba, Bajo Cauca and Medellin,” said the prosecutor Rendon. Now, based on information from the human rights organization Indepaz, which monitors the presence of criminal groups throughout the country, the Urabeños have a presence in 264 municipalities in 23 states, making it the most active and widely present criminal group in Colombia.

The “Gaitanists” are organized according to a pyramid structure at the top of which sit “Otoniel” and “Marcos Gavilan,” men who have forged their careers over three decades fighting in various wars. Thanks to their time in the ranks of the EPL guerillas, they know the thickly forested and mountainous region of Uraba like no one else.

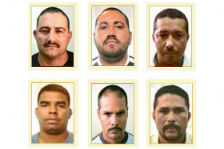

In order of importance, the following men also sit at the top of the organization’s structure: Carlos Antonio Moreno, alias “Nicolas,” Luis Orlando Padierna, alias “Inglaterra,” Jobanis de Jesus Avila, alias “Chiquito Malo,” Jhoni Alberto Grajales, alias “Guajiro,” Jairo de Jesus Durango, alias “Guagua,” Aristides Manuel Meza, alias ‘El Indio,” and Oscar David Pulgarin, alias “Niño.”

In addition to these top leaders, authorities have also identified the structures through which the “Gaitanist’s” operate. Authorities now know that the Antioquian region of Bajo Cauca is controlled by the Pacifiers of Bajo Cauca Bloc, made up of the Jose Felipe Reyes, Julio Cesar Vargas and Liberators of Bajo Cauca fronts. While in the west and northeast of Antioquia, there is the Juan de Dios Usuga Bloc, made up of the Ivan Arboleda Garces, Heroes of the Northeast, and the Carlos Mauricio Garcia Fernandez fronts.

These structures have established alliances based around mining and drug trafficking with fronts of the guerrilla rebels of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN). However, these alliances are unstable and volatile as evidenced by recent events in Bajo Cauca, where standoffs between the Urabeños and the ELN have been increasing in both frequency and intensity.

The group’s stronghold of Uraba in the states of Antioquia and Choco, meanwhile, is the domain of the Central Uraba Bloc, which is made up of the Central Uraba, Dabeiba, Carlos Vazquez, Nicolas Sierra, Riosucio-Carmen, and the Chocoan Darien fronts. Estimates from the Attorney General’s office indicate that just these fronts alone could be made up of 600 fighters.

“They are all part of an army. They have a high level of military-style organization. They know how to fight. You shouldn’t forget that ‘Otoniel’ and ‘Marcos Gavila’ were militarized during their time in the EPL and that ‘Otoniel’ was leader of the Centauros Bloc. Authorities have intercepted significant amounts of weapons, uniforms, and other equipment,” says Rendon.

And why the name Gaitanists? “Their Gaitanist philosophy is supposedly one that rails against corruption and politicking. Whoever wants to go further in their criminal structure has to study the works of Gaitan,” said Rendon.

A Large Criminal Portfolio

The Urabeños tentacles extend from forests of the Darien in the north western state of Choco, pass through Colombia’s major cities, and even reach international borders and their sizable criminal portfolio includes extortion of businesses, loansharking, drug trafficking, and, more recently, human smuggling.

“Getting migrants into Panama is a robust business for them” one resident of the Uraba municipality of Acandi told Verdad Abierta. “In addition to getting the migrants to the border and supplying them with false paperwork, they load them up with cocaine and force them to transport it to their people on the other side of the border. If the migrants refuse, they kill them. And they can do it because they have complete control of the coastal and forested areas used by the migrants to cross the border.”

It is precisely this financial component of the organization’s work that authorities say they have been able to strike hardest. Operation Agamemnon has resulted in the arrests of 400 people, and the seizure of properties valued at over $600,000 USD, and 9.8 tons of cocaine.

“Today, the finances of the organization are badly damaged. There are parts of the country where the organization can’t make payroll, and there are members that are turning themselves in to the authorities,” says Redon. “Today we have their financing structure identified. Strangling their income streams will be much easier and faster than capturing Otoniel.”

But do these results justify the show of force and resources that Operation Agamemnon has entailed? There are some who say that it doesn’t. Some of the most vocal critics of the operation have been the rural and indigenous communities of the region who feel mistreated by the authorities.

SEE ALSO: Profile of “Otoniel”

“The poor rural populations are being constantly stigmatized because the police say they haven’t found ‘Otoniel’ yet because the residents of rural communities are protecting him,” complained Diego Herrera, president of the Popular Training Institute (IPC), an organization that works with poor rural communities in Uraba. He went on to say, “they arbitrarily detain anyone with the last name Usuga, as if that itself were a crime.”

Aida Suarez, president of the Antioquia Indigenous Organization (OIA) makes similar claims. “In the last year, in the interior territories of Polines, between Chigorodo and Carepa, the guerrillas and criminal groups have begun to make their presence known,” she said. “When the public security forces arrived in the territory the battles began, and members of these armed groups hid in indigenous territory. In July, there were three large confrontations in our area.”

The tension from constant fighting in the region only got worse on August 4 when an Air Force helicopter fell from the sky under suspicious circumstances, killing 16 troops. The helicopter crash forced 147 families from their homes. “There are approximately 600 people there that are refugees. But more than anything, what worries us are the statements from the police saying that we are protecting the armed groups,” she added.

Verdad Abierta attempted to speak with Police Commander in charge of Operation Agamemnon, Ricardo Restrepo, but was unable to reach him.

Moving beyond the debate regarding the success or failure of the operation, what has been discovered so far makes it clear that the so-called Clan Usuga is much more than a simple criminal organization. Defeating them will require aggressive efforts by public security forces. Natalia Rendon might be right when she says, “there are some things more important than capturing Otoniel: now we know the enemy we are up against.”

*This article originaly appeared in Verdad Abierta and was translated and reproduced with permission. See original article here.