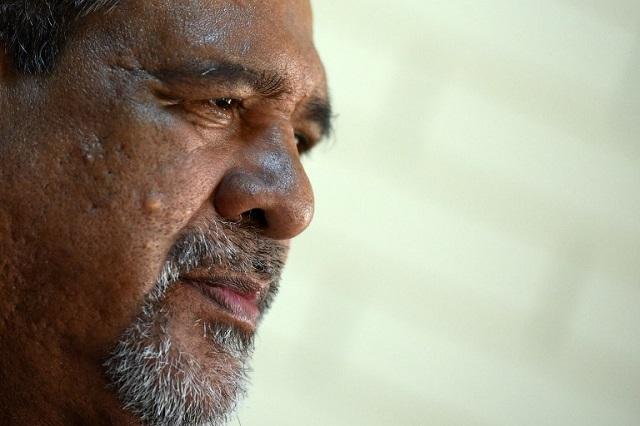

The name “Raul Mijango” annoys a significant portion of society, but an undeniable fact remains: few people know Salvadoran gangs as well as him. The public face of El Salvador’s gang truce, in this interview says goodbye to his creation. He blames the United States, Attorney General Luis Martinez, former Minister of Security Ricardo Perdomo, and the FMLN for destroying the truce. He also criticizes the lack of will among the gangs.

Raul Mijango closes and locks it. Although he prefers to qualify it, the last enthusiast of the gang negotiation as a way to stop violence, turns over the keys of his office as truce mediator, and looks for other battles to join. Others that are not yet lost.

This is part one of a story that originally appeared in El Faro’s Sala Negra, a version of which was translated and reprinted with permission. See Spanish original here.

In this interview, Mijango leaves behind the little moderation he has for diplomacy and politically correct language: the “gringos” he says, were the main conspirators against the process he is considered as having created, and were aided by officials eager to be liked, such as Attorney General Luis Martinez and former minister, Ricardo Perdomo.

Through his experience as truce mediator, he claims to have acquired the ability to “prophesize” what would occur and, strange as it sounds, some predictions prove him right. For instance, he warned that, with the end of the truce, murders would double or triple. This has happened. He also warned the gangs would enter into a bloody anarchy. This has happened. Now that the truce is over, he warns it will take five or ten extremely violent years before anyone dares to mention dialogue with the gangs as an option.

For now, he has emptied his office, taking his certificates, diplomas prepared by gang members, a national map with colors indicating municipalities that have already received intervention or were about to, and a small sign that reads, “Do not give up, it’s not yet over.”

Since 2012 you have been optimistic about the truce; in both good and bad times. What convinced you the process had reached a dead end?

In March 2012, the opportunity opened to begin a process to resolve the problem of violence. It was a very intense 15 months, and we did much more than what we had anticipated. I think in the future, when violence is analyzed, they will have to study the “pre-truce” and “post-truce.” The truce showed the problem of violence can be solved when approached in a way different than repression.

What role did the presidential campaign have in the truce’s failure?

The two major parties, the FMLN and ARENA, were well aware of the electoral weight the gangs represented, especially with the social groups that revolve around them. It’s no secret in the months before the election the two parties wanted to win those votes. After the second round victory of Salvador Sanchez Ceren, a different chapter opened in the country. In the case of the gangs, this victory brought hope the process could be revived. This was not only because it was a leftist government, but because, as I understand, they had private conversations, and an element that was always on the table was to facilitate the continuation of this process.

Talks between the FMLN and the gangs?

Yes.

Talks between the incoming government and the gangs?

Of course.

What your saying is an assumption, or do you have evidence?

I know there were meetings of gang leaders with the FMLN, and on the table was the continuity of the process.

Do you believe or know?

I know. And those conversations filled gang members with expectations, expectations that proved wrong when the new government assumed office. The political direction on the issue of violence was completely different from what had been discussed.

May 2014, the month prior to the inauguration of Sanchez Ceren, was very violent. How do you explain this if the gangs had well-founded hopes for the new government?

The explanations I heard at that time revolved around the repressive actions being promoted by the then Minister of Public Security, Ricardo Perdomo, which caused a violent reaction. What I was told was that I had to wait until Perdomo left the scene, because he was the one blocking the resumption of the process.

You do not include the year of Perdomo (June 2013 to May 2014) as a time when the truce was active?

Not at all. 2013 proved to be the year in which violence levels were reduced the most. But if you do the math, this was in the first half of the year.

But throughout 2014 you continued speaking about the truce as if it was an active process.

Because what they had said to me was that the new government had the idea of continuing. And, for me, this created an expectation that, although the process had entered into crisis, it could be revitalized. That was the foundation for the optimism that I expressed.

You mediated between the FMLN delegates and gang leaders? You put them in contact?

No. I’ve been very careful with that sort of thing, because the political factor is that more harm can be done to any action that seeks to solve the problem of violence. Why? Because parties in a spectrum as polarized as in El Salvador always seek political gain. That’s why I always made an effort to stay semi-neutral, because I was convinced that for the process to be successful, I had to stake out its territory. And on the ground you have to work with mayors of different parties, and I could not become partial. In addition, the FMLN could engage in discussions directly, without mediators, and they did. I did not participate in those discussions, although of course I was immediately informed. I even heard recordings that were made…

There are recordings of these meetings between FMLN leaders and the gangs’ spokesmen?

There are. I don’t have them, but I’ve heard them.

Who from the FMLN participated in those meetings?

[A couple seconds of guarded silence] People with decision-making authority participated. That’s all I’ll say.

People who read this may think you are inventing everything to tarnish the name of the FMLN.

No, because the same can be said of ARENA. There were also representatives from that party with decision-making powers who had conversations with the gangs. Some photographs of those meetings were leaked. And that’s not bad! If a gang member is free and there are no criminal proceedings against him, they’re a person who can be spoken with.

Why omit the names of the parties’ negotiators?

Because I was not at those meetings. I knew of them by other means. Those who would have to explain that there are those who were there: representatives of the gangs’ national ranflas [leadership councils], and people with decision-making power from both parties. But let’s get to the point: the point is an expectation was created that the process could be revied for the country’s benefit. And I say the country because nobody is going to say that having 30 homicides a day is better than five. I’ll never believe that! So, there were second chances to reduce homicidies. When did this possibility end? When Sanchez Ceren gave his fateful statement in January 2015 that was interpreted by the gangs as a declaration of war. And from there everything has gotten worse, arriving at the situation we have today.

The second half of 2014 was a period of uncertainty …

There was a kind of silence about the topic.

In September you presented before the National Council for Public Security and Coexistence, and you said they had to give you the benefit of the doubt.

Today I feel that the possibilities of building peace in the country have been exhausted, and now it’s a matter of waiting for the thirst for blood and death, both among the gangs and government, to be quenched before reconsidering what is necessary to work for peace. How long will this last? I do not know, but, in my experience living through the armed conflict of the 1980s, it took 10 years and more than 50,000 dead. The first proposal for seeking a negotiated solution was in 1982, but at that time both sides believed in military victory. It’s the same now, with the government seeking a military victory when a negotiated solution would save time, lives, and suffering. And it would resolve the problem effectively, as we demonstrated in 2012.

SEE ALSO: Coverage of El Salvador’s Gang Truce

Why do you always you like to draw parallels between the civil war of the ‘80s and the gang phenomenon?

Because, in my opinion, they are similar conflicts; not on the political-ideological level, but the social causes that generated them are the same.

But you are aware the comparison is offensive to many people who were fighters in their day…

Yes, to those who are now in the government and want to defend the status quo. I do not! I am not obliged to defend the Constitution. I’m not forced! Why? Because I do not share the economic and political system that arises from the Constitution, which is plutocratic in character, designed to favor the ruling classes. I think you have to change the system, and we all had expectations that, paralleling Schafik [Jorge Handal – the former head of the Salvadoran Communist Party], when the left came to power it would seek to transform from within. But we have witnessed in the past six years, that the system ended up transforming the left.

Does not it seem a little simplified to say that the causes of the civil war are the same that feed the gang phenomenon?

You can’t just see the gangs as criminal groups, but as a social phenomenon. And when you see them as a social phenomenon, of course the causes that move them are structural, as in war. These causes have influenced not only the origin of the problem, but also its development, its growth, and in how the gangs have us in the situation we find ourselves as a country: subdued. The violence generated by these types of groups is a consequence of the socio-economic and political model that we have.

You now say that the truce ended in June 2013. What objective reasons are there to throw in the towel today that were not present in July 2013 or over 2014?

Things have occurred that allow me to support this belief. The first is that there was an oral expression from the president in which he favored repressive solutions and expressed that there is no space for any dialogue, let alone understandings, with gangs. Another element is that, from when I was deprived of the opportunity to act as intermediary for the gangs, I have insisted on the idea of committing them to initiate a unilateral process to help transform this situation, so that the gang members assume the task of working for peace. And in a passionate call I made recently, I challenged the gangs. I asked them to develop a process of violence reduction without asking anything in return. And what answer did I receive? A significant increase in the number of murders.

The homicide figures convinced you the gangs didn’t want to engage in dialogue either.

I was convinced they did not want to begin a unilateral process. They feel attacked by the government, and feel it is their right to respond in kind. The consequence is that the two parties have opted for violence, and in these conditions there is no room to work for peace. For dialogue, political will is required. And today you will see that will in neither the government nor gangs. Each side has its own justification, but in the end it comes down to the fact that there is no will. Why? Because things are getting more complex. In 2012, to control the problem of violence in the country, we struggled with six groups: the MS13, the two Barrio 18s, the Mao-Mao, La Mirada, and La Maquina. With everything that’s happened, you now have to deal with 700 cliques. Each group, with the wrong strategy for combatting the problem, has generated a level of … of … how do I put it?

Of atomization?

Atomization no. Of… anarchy. An anarchy in which hundreds of groups have fallen that before responded to the directives of the national ranflas, but that now operate autonomously, united only by the idea of engaging in violence. With these levels of anarchy, developing a process of violence reduction, with the threat that seeking peace can be typified as an act of terrorism by the Attorney General, means I have concluded the space to work is no longer present.

*This is part one of a story that originally appeared in El Faro’s Sala Negra, a version of which was translated and reprinted with permission. See Spanish original here.