The entrance to the Honduran border town of Camasca is well-guarded. A column of the army’s special forces stops vehicles along the paved road that winds through the mountains to La Esperanza, the capital of the department of Intibucá.

The soldiers are here for just one reason: the intrusion of the MS13 gang from neighboring El Salvador into Honduras’ borderlands.

This terror arrived in Camasca, a de facto regional capital, and its surrounding areas toward the end of 2016. As Mara Salvatrucha graffiti began to multiply, houses began to empty.

Disturbing stories began to make their way to Camasca from Colomoncagua and Magdalena, two of the villages closest to the Salvadoran border. Murders that began with bullets and ended with bodies chopped up with machetes. Payments of $100 demanded every two weeks from those known to be receiving remittances from the United States. Who was responsible for it all? A Salvadoran gang leader who recruited Honduran youth under the banner of the MS.

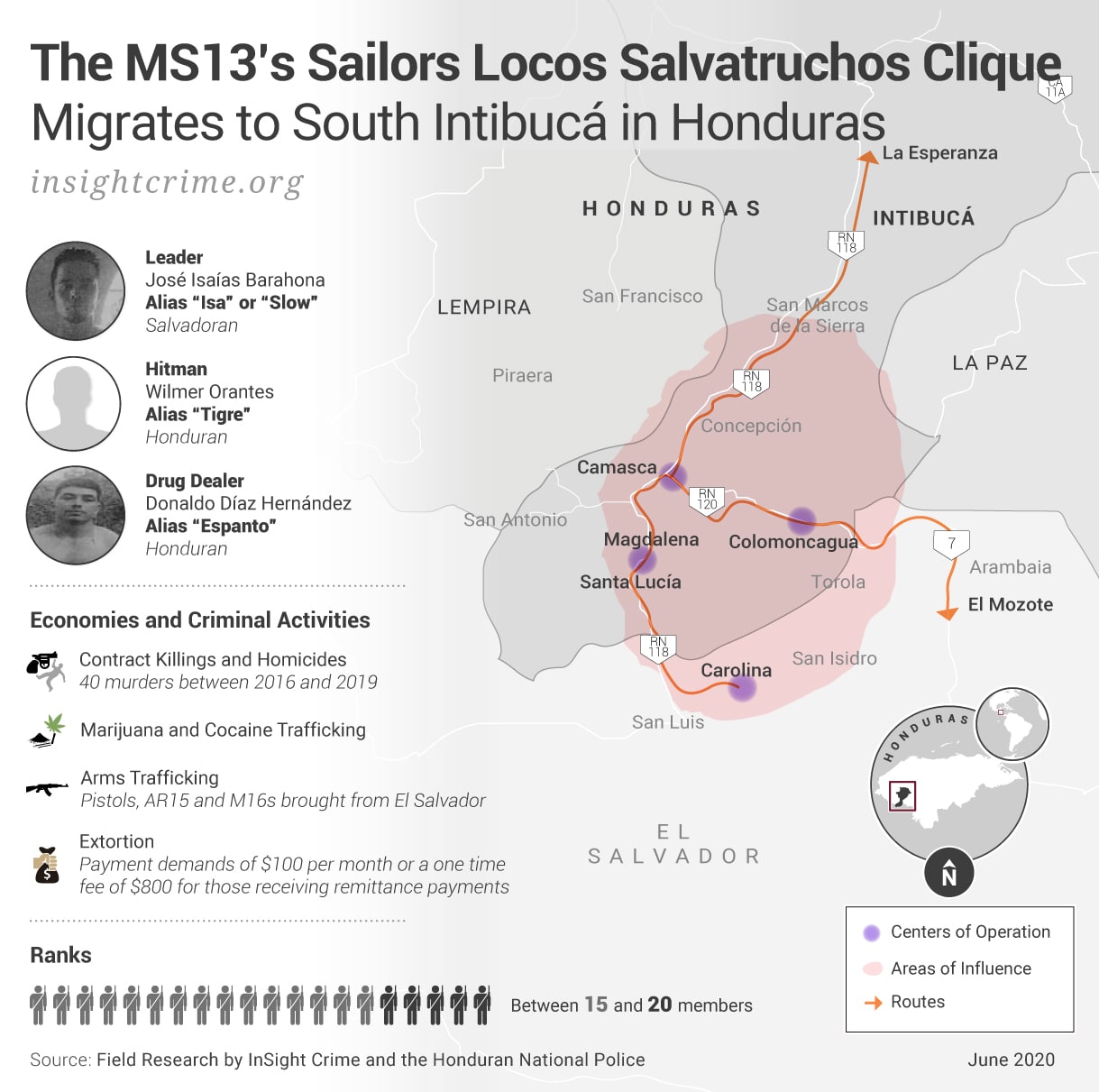

His name: José Isaías Barahona, also known in Honduras as “Isa,” and by his gang name “Slow,” according to the investigation opened by the Honduran police to which InSight Crime gained access. Isaías is a member of the Sailors Locos Salvatruchos (SLS), one of MS13’s oldest cliques. The cell dates back to the 1990s in San Miguel, a Salvadoran department on the border with Intibucá.

SEE ALSO: Honduras News and Profile

Between 2016 and 2018, Isaías recruited at least 15 other young men, most of them Hondurans, according to Honduran government sources who have followed the evolution of MS13 in Intibucá. With his new recruits, Isaías formed a group that the Honduran Nacional Police (Policía Nacional – PN) has termed “Los Colochos.”

By 2017, the Sailors branch in the south of Intibucá had access to a heavy arsenal, pistols, shotguns and AR-15 assault rifles. Between 2016 and 2019, the clique murdered some 40 people “for not paying extortions, or on suspicion that [the victims] were informants for authorities,” Edgardo Tejada, an inspector for the Honduran National Police assigned to anti-gang operations in the region, told InSight Crime.

In addition to committing homicides and demanding extortion payments — the hallmarks of MS13 — Isías’ clique was involved in small-time drug sales and trafficking of marijuana and cocaine, Tejada said. From Siguatepeque, a rural Honduran town in the Comayagua department, “they were getting marijuana to move into El Salvador,” Tejada said.

The National Police, however, still don’t consider the MS13 cell to be an important player in Intibucá’s cocaine scene. Cocaine, according to police sources and human rights advocates in the region, remains in the hands of the large drug trafficking groups.

The mainstay of the Sailors cell in Intibucá, for the moment, is extortion.

Another police officer located in Camasca, whose name and rank InSight Crime has omitted for safety, said that they began “coming and going across all areas of the border” in 2016.

“By 2017, there were already a lot of massacres,” the officer said, adding that people began to flee. The situation continued to get worse in 2018, with more than 90 families abandoning their homes in the towns of Magdalena and Colomoncagua, just over the El Salvador border.

It wasn’t until August 2019 that the Honduran government sent a permanent army presence and additional police to Camasca to address the increase in violence. The situation has been slow to improve.

Calls for assistance from residents of Camasca and neighboring towns were still routed to La Esperanza, Intibucá’s capital, over an hour away by car. In November, the Honduran National Commission for Human Rights (Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos de Honduras – CONADEH) in La Esperanza sent a team to Camasca and Colomoncagua. The group was provided a military escort.

“There were no formal complaints, but there were accounts of people forced by MS13 to leave their homes. The people arrived at the [police station] but, out of fear, wouldn’t file a complaint,” said a human rights advocate in Intibucá who spoke with InSight Crime but asked that her name not be published for security reasons.

“We realized that there had been an increase in violent deaths and that people had been butchered in Colomoncagua,” the human rights official said.

Ravaged Lands

Everything started with the arrival of Isaías, or Slow, who fled across the border amid a crackdown on gangs in El Salvador by former president Salvador Sánchez Cerén (2014-2019). In 2016, Sánchez Cerén tightened security in prisons, but, more importantly, he deployed heavily armed military units to rural areas under the control of the MS13 and its rival, the Barrio 18 gang.

Farmers and business owners tired of gang rule also contracted officers and soldiers to kill gang members. San Miguel, the stronghold of the Sailors Locos Salvatruchos, was a center for such death squads.

The migration of the Isaías MS13 cell over the Honduras border is what crime experts call the cockroach effect, in which pressure in one region forces crime groups to move into less guarded areas. Intibucá’s towns were unprepared for who came over the border.

Isaías soon taught his Honduran recruits the MS13’s principal tactic: brutal violence. He was also the one who set them off to collect extortion payments, the criminal economy that has sustained the group since its creation is its main source of illicit proceeds.

Intibucá, he found, was fertile ground for an extortion racket.

SEE ALSO: MS13 in the Americas

On the road that begins in La Esperanza, winding through the coffee plantations and mountains that stretch to the border with El Salvador, two-story houses of cement and iron have replaced the region’s traditional ranch houses of mud and straw. Remittances sent from the United States built the stretch of new homes.

The town of Colomoncagua, which thirty years ago received thousands of Salvadorans fleeing the country’s civil war, now says goodbye to scores of Hondurans heading north in search of work, according to an immigration officer in the neighboring Honduran department of Lempira.

In Intibucá, some 37,000 people, or 13 percent of the residential population, received remittances from family members abroad in 2018, according to data collected by Honduras’ election authority. According to Miguel Antonio Fajardo, the mayor of Intibucá’s capital, a significant percentage of those receiving remittances are concentrated in the department’s south.

Inspector Tejada explained that the gang was able to identify recipients of remittances in towns like Magdalena and Colomoncagua and began to charge them as much as $100 every two weeks. According to a police officer in Camasca, some extortion payments went as high as one-off payments of 80,000 lempiras (about $3,200). According to a study by the Inter-American Development Bank, the average monthly remittance a Honduran might receive is $166.

Corpses began to turn up. In Magdalena alone, the clique killed 18 people in the first few months of 2017, according to the National Police. A representative of CONADEH in Intibucá confirmed the figure.

By 2017, Isaías had recruited two Hondurans — Wilmer Orantes, alias “Tiger,” and Donaldo Díaz Hernández, alias “The Terror” — to serve as his lieutenants and principal killers, according to police reports reviewed by InSight Crime. The two took charge of his bloody orders. Investigators say they killed a Barrio 18 member in Jesús de Otoro, a village north of Camasca. They are also accused of murdering a pregnant teacher in the same village. According to the version of events told to CONADEH, the gang members dismembered and disposed of her body in a dumpster.

Orantes — accused of various crimes — was jailed, but his lawyers were able to get him released in November 2019 after paying a fine of 300,000 lempiras (around $12,000), a police officer in Camasca told InSight Crime. “In our country, everything can be settled with money,” the officer said. Meanwhile, Díaz, who was responsible for procuring drugs for the clique, was detained in 2019 on suspicion that he killed an informant in Camaca.

The gang violence has also sparked responses from other groups in places like Jesús de Otoro and Camasca, where some citizens have taken to arming themselves. “They’ve already formed a death squad,” said the police source in Camasca.

All of this, in addition to the presence of the army in the south of Intibucá, has forced the gang members to maintain a low profile lately, according to the PN.

Isaías currently moves between Magdalena in Honduras and Carolina in El Salvador. According to the police, he continues to supply arms to the clique. “From El Salvador, he’s brought AR15s and M16s,” said the police officer in Camasca. He has made sure that his clique remains capable of moving between the two countries, finding refuge in the mountains of southern Intibucá, or on the outskirts of Carolina, north of San Miguel.

The terror keeps moving but is far from gone.

* Victoria Dittmar and Alex Papadovassilakis contributed to this article.