A series of high-profile takedowns have ensured that the fragmentation of Mexico’s criminal groups has continued apace, with several of the largest groups now operating as little more than collections of allied cells rather than coherent organizations under a unified chain of command.

A recent article from Razon

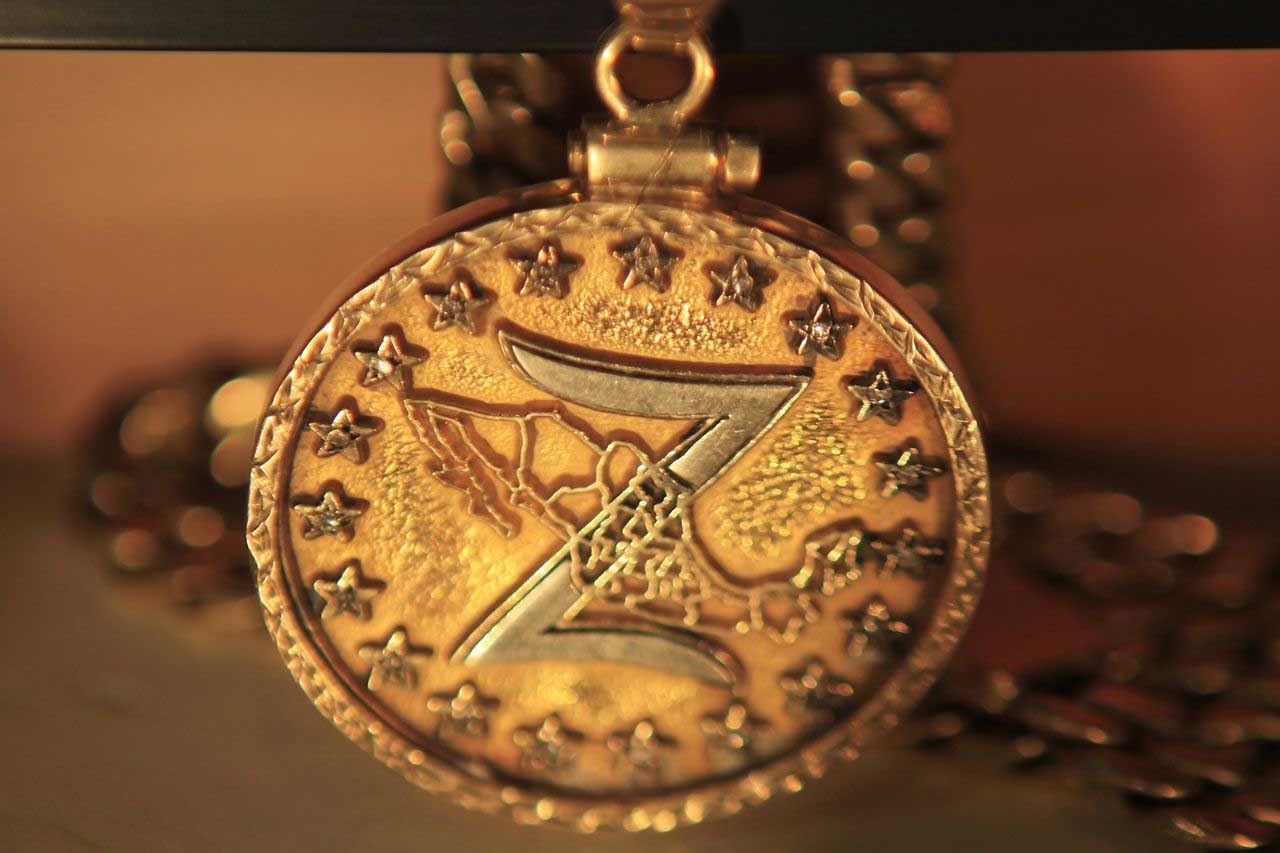

, based on a confidential report from Mexico’s office of the Attorney General (known by its Spanish initials as the PGR), detailed the breakdown of some of Mexico’s most important criminal organizations: the Gulf Cartel, the Tijuana Cartel, the Sinaloa Cartel, the Zetas, the Beltran Leyva Organization, and the Familia Michoacana. These groups collectively control virtually the entire border region, as well as some of the most sought-after criminal real estate elsewhere in the nation, from key port cities to fertile production areas to key transport zones.

They all emerged as large organizations whose public face was a single individual or small group of leaders. In other words, they were hierarchical. That perception may have been exaggerated; the degree of influence that a fugitive drug lord like Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman could exercise over the inner-workings of a vast organization with countless moving parts was likely somewhat limited, and different figures within the organization likely enjoyed much autonomy. But the popular perception clearly reflected some version of reality, and internal rivalries between different wings of an organization were once quite rare.

The PGR report offers further evidence that this has changed. The large organizations have all been surpassed to some degree or another by the smaller cells of which they have long been made up. The difference today is that the cells are more autonomous, more geographically isolated, and less referential to any single leader. As a result, the old conceptualization of the cartel as a coherent nationwide organization with contacts around the globe is fading.

For instance, the PGR reports that the Gulf Cartel has reorganized into at least 12 different cells, the majority of which operate in Tamaulipas: Los Metros, Los Rojos, Grupo Lacoste, Grupo Dragones, Grupo Bravo, Grupo Pumas, Los M3, Los Fresitas, Los Sierra, Los Pantera, Los Ciclones, and Los Pelones. The pattern of a large number of splinter cells operating in overlapping territory is similar for the Zetas and the Gulf Cartel, among others.

And they don’t always get along. The mere adoption of different monikers suggests a certain degree of distance that is in danger of spilling into open conflict. There have already been multiple examples of this. Los Metros and Los Rojos, to take but one example, were engaged in an ongoing dispute for leadership

of the Gulf Cartel in 2012 and 2013. Different elements of the Zetas have been fighting each other as far back as 2012 as well.

InSight Crime Analysis

The upsurge of different factions makes organized crime violence harder to eradicate. Compared to the transnational organizations led by seemingly untouchable bosses, today’s gangs are less able to threaten the state and less endowed with impunity. However, the mere presence of a greater number of actors makes establishing a tacit set of operating norms that much harder, and increases the likelihood of violent rivalries.

While the PGR document appears to be more explicit than prior government reporting on the issue, this is not a new phenomenon. InSight Crime and other analysts have been writing about the potential impact of the fracturing of Mexico’s traditional organizations for several years. It is now a basic fact of Mexico’s security climate, and there is no reason to expect the phenomenon to slow, much less reverse itself.

SEE ALSO:More Mexico Organized Crime News

The fracturing is the product of a variety of different factors, the most important of which is continuing government pressure. As a result of a sustained push to arrest the generation of capos that has run Mexico’s underworld since the beginning of this millennium, dozens of the most prominent criminal leaders have dropped from the scene.

This evolution requires a new set of priorities from Mexico’s government. President Peña Nieto campaigned on a new approach to security, in which he would de-emphasize the importance of security to his overall agenda, and in which he would also downplay the kingpin strategy as a part of his security policy. And while Peña Nieto has largely lived up to the first promise, his team has been arguably as focused on taking down the biggest names in Mexican organized crime as were his predecessors.

Under the current administration, the longtime leaders of the Zetas (Miguel Angel Treviño and Omar Treviño), the Sinaloa Cartel (Guzman), and the Knights Templar (Servando Gomez and Nazario Moreno Gonzalez) have been either arrested or killed. Even beyond those famous names, Peña Nieto’s administration compiled a list of 122 of the most wanted capos, and has set about capturing or killing all of them. As of March, only 30 remained

on the loose.

There are some simple reasons behind the sustained pursuit of kingpins; it is conceptually easy to grasp and to design; when it works, it is easy to sell to the public as a success; and after years of practice, the Mexican authorities have gotten quite good at it.

However, in an era in which the Gulf Cartel is not a single organization but rather an amalgamation of 12 loosely aligned cells, targeting the biggest bad guy is of limited value from the standpoint of altering the reality on the ground. A Gulf Cartel led by 12 low-profile chieftains is a fundamentally different challenge than the monolith operating under the sole authority of Osiel Cardenas. The current model is just as able to generate bloodshed, but without a figurehead to serve as an obvious target, it’s not as easy for the government to weaken.

The proper approach now is to foster the growth of capable, honest, and self-perpetuating institutions at the federal and local level. Of course, the institutions of primary importance are Mexico’s security agencies, but better police departments alone are not sufficient. More than ever before, Mexico’s security challenge is not one of overcoming singularly powerful enemies, but rather creating a social, economic and political framework capable of dealing with both the root causes and the immediate manifestations of organized crime.

Unfortunately, this is an easier task to describe than it is to complete.