Venezuela remained mired in crisis throughout 2019, yet Nicolás Maduro actually consolidated his regime. How did he do it? He financed the government with stolen gold, made profitable alliances with military officials, congressional strongmen, wealthy business elites and criminal groups, and staved off a bumbling opposition.

Gold, Gold Everywhere

A country once dependent on one commodity seems to have switched to another. While oil production has dwindled, the once-proud OPEC nation has turned to minerals, most notably gold, to keep the government solvent. In short, Venezuela’s Orinoco Mining Arc has been a piggy bank for the Maduro regime and his family. And in 2019, it was also used to help pay off political allies, lure in Colombian guerrilla groups, and as an expansion ground for domestic criminal gangs looking to diversify.

In an interview with the Washington Post, a former intelligence official who deserted in April 2019, said the Maduro family heads up a racket aiming at pillaging gold mines in the south of the country, by buying up the gold at low cost and then selling it overseas through the central bank.

The president’s son, Nicolás Maduro Guerra, often referred to as Nicolasito, headed up the scheme. Maduro Guerra also placed trusted figures at the head of the state-owned mining company, Minerven (Compañía General de Minería de Venezuela). Close to him in these schemes is Alex Saab, long known as one of the Maduro family’s preferred financial operators.

“(Nicolás) Maduro is the head of a criminal enterprise. His own family is involved,” Manuel Ricardo Cristopher Figuera, an army general and former director of the feared Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (Servicio Bolivariano de Inteligencia Nacional – SEBIN), said to the Post.

SEE ALSO: US Targets Children of Venezuela President and First Lady

This dirty money belonging to Maduro and his allies circulates through the international financial system through sophisticated money laundering schemes and a range of foreign and local operators, which have succeeded in sidestepping a growing number of sanctions against Caracas. Other criminal states, such as Russia, help to launder criminal profits.

Maduro has also actively allowed, if not enticed, elements from Colombian guerrilla groups, such as the ex-FARC Mafia (dissident elements of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC) and the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional – ELN) to dig up Venezuela’s gold. They have fed the gold assets sold off by state elites, sidestepping foreign sanctions.

This pipeline of gold is essential for Maduro to remain in office, enabling him to meet the state payroll, grease the palms of his subordinates and providing him with much needed foreign currency.

According to a Transparencia Venezuela report, “in total, along different routes…gold worth $3 billion was lost between 1998 and 2016, be it through Aruba, Curacao and Bonaire, through Holland and Belgium, and through the United States, Switzerland, the United Arab Emirates and China. The bleeding of the Orinoco Mining Arc was substantial.”

That money appears to be the tip of the iceberg. In October, Maduro promised to hand over the control of one gold mine to every allied state governor to help finance local budgets. According to the president, this was necessary due to the pressure of US sanctions and would allow state governments to access millions of dollars a month in mineral wealth. State governments held by the opposition are excluded from the program.

However, he gave no details on how this process would work or be supervised. It appears that these handovers, should they take place, would be state-sanctioned corruption, in exchange for loyalty. But while Maduro may be seeing this as a way to shore up domestic political loyalties, giving such ready sources of funding to state governors risks accelerating the consolidation of local criminal fiefdoms.

SEE ALSO: Southern Venezuela: A ‘Gold Mine’ for Organized Crime

Precise estimations of the amount of gold looted from Venezuela’s mines are difficult to come by, but the looting has only worsened during 2019. As sanctions have increased supervision on the Venezuelan gold industry, more clandestine and illegal routes have been utilized to move the bullion.

And with increased supervision of companies suspected of commercial links to the Venezuelan government, a free-for-all seems to be taking place, with hundreds of kilograms of gold being stashed on individual planes bound for the US, Switzerland, Turkey, Dubai and more.

Nor have Maduro and his inner circle given up on recovering gold which has been seized overseas. In October, a British financier was discovered to be discussing with Venezuelan officials an unlikely scenario to recover around $1.5 billion of Venezuelan gold retained by the Bank of England. While it is unclear just how these captures have affected the foreign reserves of Venezuelan elites, the sums being moved abroad tell they are ready to take the risk.

Impunity for Criminal Networks from Home and Abroad

At a time when Colombia’s government is taking a firmer line against Venezuela, including pushing for the United Nations to intervene, Maduro is looking for deterrents. Allowing criminal actors, both foreign and domestic, to grow with calculated impunity is a strong start.

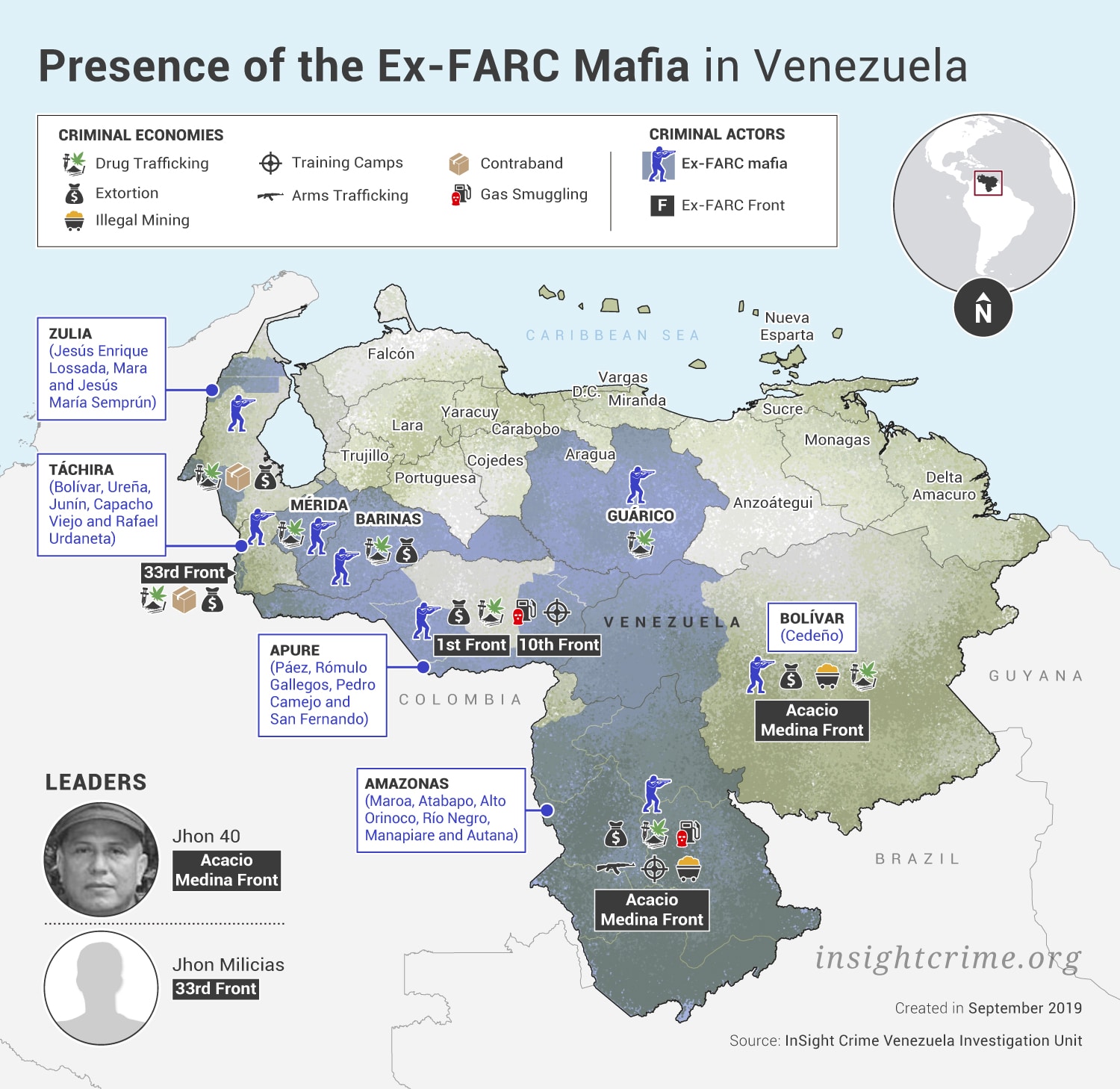

In 2019, the open welcome given to the ELN and the ex-FARC mafia by the Venezuelan government helped turn the first group into a Colombo-Venezuelan group, with the ex-FARC mafia also setting up a strong footprint in the country and recruiting desperate Venezuelans.

The clearest example of this welcome came in July when Maduro called former FARC leaders, Iván Márquez and Jesús Santrich, “leaders of peace” and stated that they were welcome in Venezuela. A month later, flanked by fellow guerrillas, the two commanders announced they were abandoning the peace process and returning to arms. In his speech, Márquez mentioned a possible alliance with the ELN, a notion made far easier by the two groups operating with impunity on Venezuelan soil.

Maduro has given these guerrillas, especially the ex-FARC mafia, a firm grip on transnational drug trafficking, creating numerous conduits to send cocaine from Colombia through Venezuela to the United States and Europe. It has allowed them to develop illegal mining as a highly lucrative criminal economy, with the army even providing protection and transportation in exchange for a share of the profits.

And the benefits are plentiful. Left isolated by sanctions and facing the potential if still remote threat of foreign intervention, Maduro may have to count on “criminal armies” to defend him should a military incursion take place. And with the US and Colombia uncertain of exactly how deep these relationships go, this makes Maduro an unpredictable and resilient foe.

This also puts Colombia and the administration of President Iván Duque on the back foot. While large rewards have been put out for Márquez and Jesús Santrich, finding them in Venezuela is hard. While it currently appears that Maduro’s support for these criminal groups has not extended past sanctuary and logistics, any further threats from Colombia and its US ally, could see him arm them as well.

What’s more, removing Maduro from power does not necessarily remove this threat. The presence of irregular armed groups involved in drug trafficking could fuel intractable civil conflict down the road, similar to that seen in neighboring Colombia.

At home, the Maduro regime has carefully built up a network of loyalties with Venezuela’s own irregular and criminal groups, as well as paramilitary groups known as the “colectivos.”

The immediacy with which he can call upon these groups to act was demonstrated in 2019. When opposition lawmaker Juan Guaidó declared himself Venezuela’s “interim president” and was recognized by the United States, one of Maduro’s first acts was to call on the support of colectivos. Several of these organizations quickly took to the streets in a show of support, becoming a Maduro-directed strike force, violently breaking up opposition protests and using other scare tactics. In February, InSight Crime pointed to the Border Security Colectivo in the border state of Táchira, which was deployed alongside police and army, its members working to impede the entry of humanitarian aid into Colombia.

SEE ALSO: Maduro Relies on ‘Colectivos’ to Stand Firm in Venezuela

But it is uncertain how deep their loyalties to Maduro run. While colectivos have backed Maduro during showdowns, such as that over foreign aid, funding from the government has also dried up. This has pushed colectivos deeper into drug trafficking and extortion to an increasing degree. An InSight Crime investigation in 2018 found that certain members of colectivos still respected Chávez with reverence but have little respect for his successor, seeing him as having betrayed “revolutionary principles.”

Alongside colectivos, megabandas (Venezuelan gangs made up of over 100 members) have expanded their criminal horizons at home and abroad. One above all, the Tren de Aragua, has thrived in 2019, expanding far beyond its home province of Aragua and setting up in Brazil, Colombia and Peru. The government has done nothing to stop the gang’s spread, even when it was linked to the murder of a high-ranking army general just miles from the prison.

For her part, the Director of Venezuela’s prison system, Iris Varela, has not hidden the fact that she believes that prisoners should also be used to defend the Maduro government. In an interview with InSight Crime in July 2019, Varela said up to 45,000 prisoners could defend Venezuela from foreign military intervention. Security experts have also told InSight Crime that Varela is in regular communication with El Tren de Aragua boss, Niño Guerrero, who is based at Tocorón prison.

Opposition Missteps

International authorities have not been idle. In June, the US Treasury Department added Maduro Guerra to its list of sanctions for his help “in sustaining the regime.” In August, the three children of Maduro’s wife, Cilia Flores, Walter Yosser and Yoswal Gavidia Flores were also targeted. But given how Maduro and his network of allies have been able to sidestep sanctions through a range of criminal economies, these sanctions may prove largely toothless.

Venezuela’s political opposition also bungled opportunities. While more than 50 countries had recognized Guaidó as the “interim leader” of Venezuela, the opposition never fully united. In February, when Guaidó vowed to bring humanitarian aid sent internationally into the country, Maduro mobilized colectivos who blocked off bridges and border crossings into Venezuela. The aid never entered.

In April, Guaidó called on the army and general public to join him in the streets. The crowd swelled to a few thousand but military factions never materialized. A jubilant Maduro proclaimed that Venezuela would never surrender to “imperialist forces.”

In September, Guaidó was photographed with leaders of a Colombian criminal group, Los Rastrojos, who are active in human smuggling and contraband along the Venezuela-Colombia border. There is no indication Guaidó had any relationship with Los Rastrojos apart from negotiating passage through territory they control but the visuals were damning all the same.

Finally, in December, it was reported that nine lawmakers from three opposition parties had allegedly lobbied for a Colombian national accused of corruption and with close ties to the Maduro government as well as to Alex Saab.

Isolated, these elements may not have particularly reinforced Maduro’s position. But as a pattern of errors, they severely weakened Guaidó’s attempts to seem cleaner and more legitimate than even the criminal regime in power.

Top Image: AP photo of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro speaking in front of a painting of Simon Bolivar