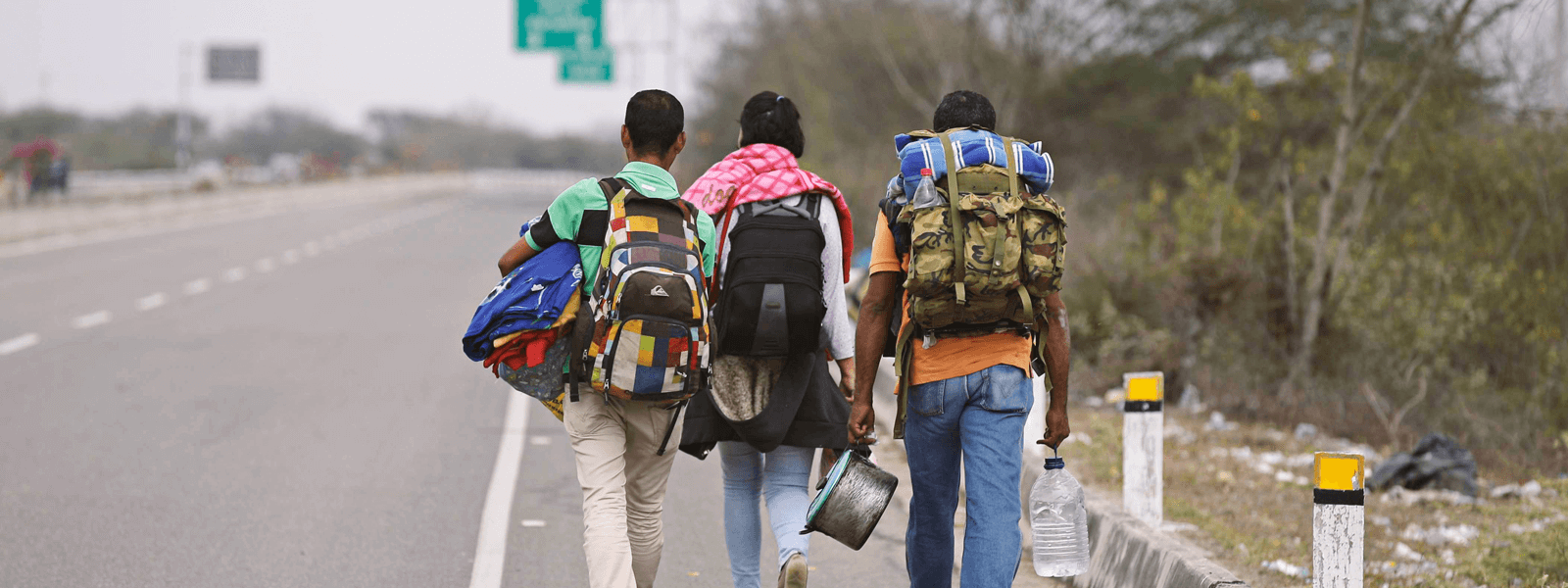

Turbulence reigned in 2018, but there was one constant: the flow of Venezuelans fleeing their country. The unceasing migration has left thousands of people homeless, penniless and ripe for exploitation by organized crime groups.

Mariana, a manicurist from the city of Maracaibo, is one example. It took her half a day to cross the border from Venezuela to Colombia. She did not need a passport or any other identification document, nor did she deal with a single immigration official. There weren’t even any rivers to cross. All she had to do was pay a little over 20,000 bolivars and 10,000 Colombian pesos (about $34 in May 2018) — all her savings at the time to reserve one of five seats in a car used by a friend to transport Venezuelans across the border from the state of Zulia via the Colombian town of Paraguachón.

The price, a relatively common amount, feeds into a basic migrant smuggling structure operating in the department of La Guajira in Colombia. People from the indigenous Wayúu population run the operation, which illegally brings Venezuelan migrants into Colombia by the thousands. At least 40 of Mariana’s relatives now live in the Colombian city of Medellín, and they used the same network to leave Venezuela.

The boom in the forced migration of Venezuelans has lasted for more than two years. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimate that approximately three million people have left the country during that time. Most migrants go to Colombia and Brazil, Venezuela’s closest neighbors. Others go to Peru, Chile, Ecuador, Argentina, Panama, Mexico and the islands of Curaçao, Aruba, and Trinidad and Tobago.

Among this massive and uncontrolled exodus, innumerable criminal economies and illicit businesses have emerged. The situation has turned the migrants into a commodity. And a rapidly spreading criminal industry is feeding on them with significant potential to replicate the perilous coyote experience between Central America, Mexico, and the United States.

Venezuela has no data estimating the number of migrants who have been smuggled or trafficked. It is also not known how many migrants have been recruited by criminal organizations operating in Colombia as they flee one of the worst crises in Latin America in recent decades.

In a recent study on migrant smuggling, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimated that at least 2.5 million migrants were victims of smuggling rings worldwide in 2016. Criminal organizations made approximately $7 billion from migrant smuggling.

For Venezuelans, the migration business straddles the border. And the first criminal structure citizens must get through is their own government. Corrupt officials operate with intermediaries to exchange bribes and extort money from people who need passports, police background checks, or certifications for their college degrees. They charge exorbitant rates for their services, often offered through the messaging service WhatsApp.

Most migrants then leave by land where things get treacherous, especially the corridor known as the Guajira peninsula. The peninsula is shared by both Colombia (La Guajira department) and Venezuela (Zulia state). On the Colombian side, human smuggling is dominated by “Los Guajiros,” as the Wayúu people in the area are often called. They impose their own tariffs to allow the movement of vehicles transporting migrants into Colombia through their territory. They also maintain a fleet of vehicles and up to 10 checkpoints on each of the more than 200 “trochas” or improvised roads that connect the two countries. To be able to cross, drivers must make payments at each control point, with the price varying constantly. Migrants or independent transporters who try to best this system not only expose themselves to robbery, abuse and sexual abuse, but also put their lives at risk.

Reports of migrant smuggling operations are growing along Venezuela’s border with Brazil as well, where the networks are run by both Brazilians and Venezuelans.

Other costs and dangers await migrants who go by sea. On the Venezuelan coast closest to Curaçao, Aruba, and Trinidad and Tobago, different modes of human smuggling have been discovered, such as using small fishing boats to transport Venezuelans to the islands, a trip such boats are unfit to make. The cost for the dangerous crossing is $350, slightly more than a plane ticket for the same trajectory. Up to 20 people board the boats at a time. So far, there are few details on how the groups running the trips are organized or how they operate, but the frequent shipwrecks and arrests of the so-called “balseros venezolanos,” or Venezuelan rafters, indicate that it could be a growing industry.

The Hungry and the Enslaved

Poverty, hunger and limited access to health services and medicine have been the engine driving the mass migration of Venezuelans, and it is only accelerating. In 2017, 87 percent of the Venezuelan population was living in poverty, according to the National Survey of Living Conditions of the Venezuelan Population (Encuesta Nacional de Condiciones de Vida de la Población Venezolana – ENCOVI), making it easier for criminal organizations to exploit them.

Most notably, Venezuelans often become victims of modern slavery and its various incarnations, such as sexual and labor exploitation. In 2018, Venezuelan non-governmental organization Paz Activa reported that there had been 198,800 victims of human trafficking as of 2017 in its publication Human Trafficking, Forced Labor and Slavery (Trata de Personas, Trabajo Forzoso y Esclavitud). Paz Activa has further warned that the figure could reach 600,000 in 2019.

The United States singled out Venezuela as a country that is not making any effort to combat human trafficking and to protect victims. Meanwhile, Colombian authorities say that human trafficking has increased along with Venezuelan migration.

This year, dozens of human trafficking, sexual exploitation and forced labor networks that specifically target Venezuelan migrants have been dismantled from Colombia, Peru, Panama, and Mexico, to the Dominican Republic and numerous countries in Europe.

In Colombia’s capital city of Bogota, 75 percent of reported trafficking victims are from Venezuela. And in smaller cities like Cartagena, Barranquilla and Armenia — the capital of Quindío department in the heart of the country’s famed coffee region — authorities have dismantled smaller networks of sexual slavery and forced labor.

They also estimate that in Cúcuta, capital of the department of Norte de Santander and a major migration gateway, there are more than 2,000 Venezuelan prostitutes, so many that prices have been driven down to as little as 10,000 Colombian pesos (approximately $3.50) for their services.

Criminal groups operating in Colombia are also taking advantage of the humanitarian crisis. Authorities in Norte de Santander told InSight Crime that all of the country’s armed groups are currently recruiting Venezuelans: The National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional – ELN), the dissidents from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC), the Rastrojos and the Urabeños all use them for different functions.The non-governmental organization the Foundation Networks (Fundación Redes) said in its latest report that Venezuelans make up some 60 percent of these groups.

Moreover, InSight Crime learned that Venezuelans have been replacing Colombian raspachines — people who harvest coca leaves — because they charge less.

“Most of the people caught up in these criminal groups are young and desperate to earn money to help their families in Venezuela,” said David Smolansky, the former mayor of the Venezuelan town of El Hatillo who is currently living in exile. Smolansky coordinates a working group on Venezuelan migrants, which the Organization of American States (OAS) created this year.

Monthly salaries when working for these criminal groups range from $100 to $300, an income that would be almost impossible to earn in Venezuela at the moment. But Venezuelans face dangers when working with such groups. In June, a bombing operation conducted by the Colombian army against a dissident FARC camp in Arauca department killed four Venezuelans, including two women.

Informal and Criminal Economies

Cúcuta is the principal corridor along the expansive border Colombia and Venezuela share. Some 40,000 Venezuelans pass through the city each day. Waves of people lug suitcases and balance packages on their shoulders as they flow into a prolific informal economy. Here, everything from cellular phones to “canaimitas” (laptops the Venezuelan government distributes to its schools) to even hair can be bought or sold.

The market for hair is particularly vibrant. As soon as they set foot on Colombian soil, Venezuelans can sell their locks for up to 100,000 Colombian pesos, which is approximately $30. In Venezuela, this amount equates to five months’ worth of minimum-wage income. The hair is used to make natural extensions that are then sold online for up to $200.

This passageway is just the first step in what is fast becoming a major corridor of migration-based organized crime. InSight Crime sources stated that a prostitution structure operates at that very point in the border, luring young women and children from the moment they arrive at the Colombian side of the Simón Bolívar bridge. They are temporarily housed in tractor-trailers, then transported to different departments throughout Colombia. Some even make it to Panama.

While it could not be confirmed through fieldwork, various regions of Colombia are notorious for having a large presence of sex workers who come from Venezuela. Cases of the sexual exploitation of Venezuelan children have also been reported in tourism enclaves like Cartagena and Santa Marta.

Borders Closed, Criminal Floodgates Open

The situation that has grown up around the Venezuelan migration has begun to significantly impact the greater region. In 2018, Latin American governments held at least two summits specifically to find a solution to the problem. The crisis is also one more on a growing list of issues tied to the already complicated migration situation affecting Central America, Mexico, and the United States.

Despite the meetings and other efforts, leaders from across the continent seem to have no effective means of tackling this crisis. Instead, the immediate reaction from many of them has been to close their countries’ borders in an attempt to squelch the growing migratory flows.

US President Donald Trump is one of the strongest advocates for that option, having proposed numerous strategies to essentially shut down the border between the United States and Mexico. Others in the region seem keen to follow his example or use it as cover for their own callous policies.

Yet, when borders are closed, migrants do not stop in their tracks; they tend to shift to more dangerous routes. And these routes are usually controlled by organized crime, thanks, in part, to chains of corruption and collusion with local authorities and security forces.

For example, Central American migrants traveling through Mexico have found themselves in the hands of organized crime groups, which are charging more for their services as Trump ramps up efforts to beef up the border. Smuggling Venezuelans is not yet as lucrative since the Venezuelan passport still allows for legal, visa-free entry to most countries in the region.

Despite hard-line responses, migration levels are not decreasing. And little has been done to tackle the reasons driving people away from their homes in Central America, Venezuela and elsewhere, such as high homicide rates, corruption, and inefficient governments.

Venezuela’s descent into crisis has largely spurred the mass migration. According to estimates from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), inflation could top one million percent by the end of 2018, and the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) could plummet by 18 percent.

The UN reports the number of Venezuelan migrants could skyrocket to 5.3 million in 2019. This increase will only fuel the market for criminal groups seeking to benefit from them, while also putting further strain on governments already incapable or unwilling to end the corruption and collusion that allow the same groups to function.

All this makes it unlikely that the situation will improve in the foreseeable future, except, of course, for organized crime.