As 2018 came to a close, two things became clear: the once impenetrable armor against corruption that the United States and other international donors provided in the region has weakened; and the political and economic elites of Central America are simply unwilling to allow not only international commissions but also their own attorneys general offices and other independent investigators to get too close for their comfort.

A single image summarizes the entire year: Guatemalan President Jimmy Morales surrounded by two dozen uniformed military officials as he announces his intention to toss out the investigations against him.

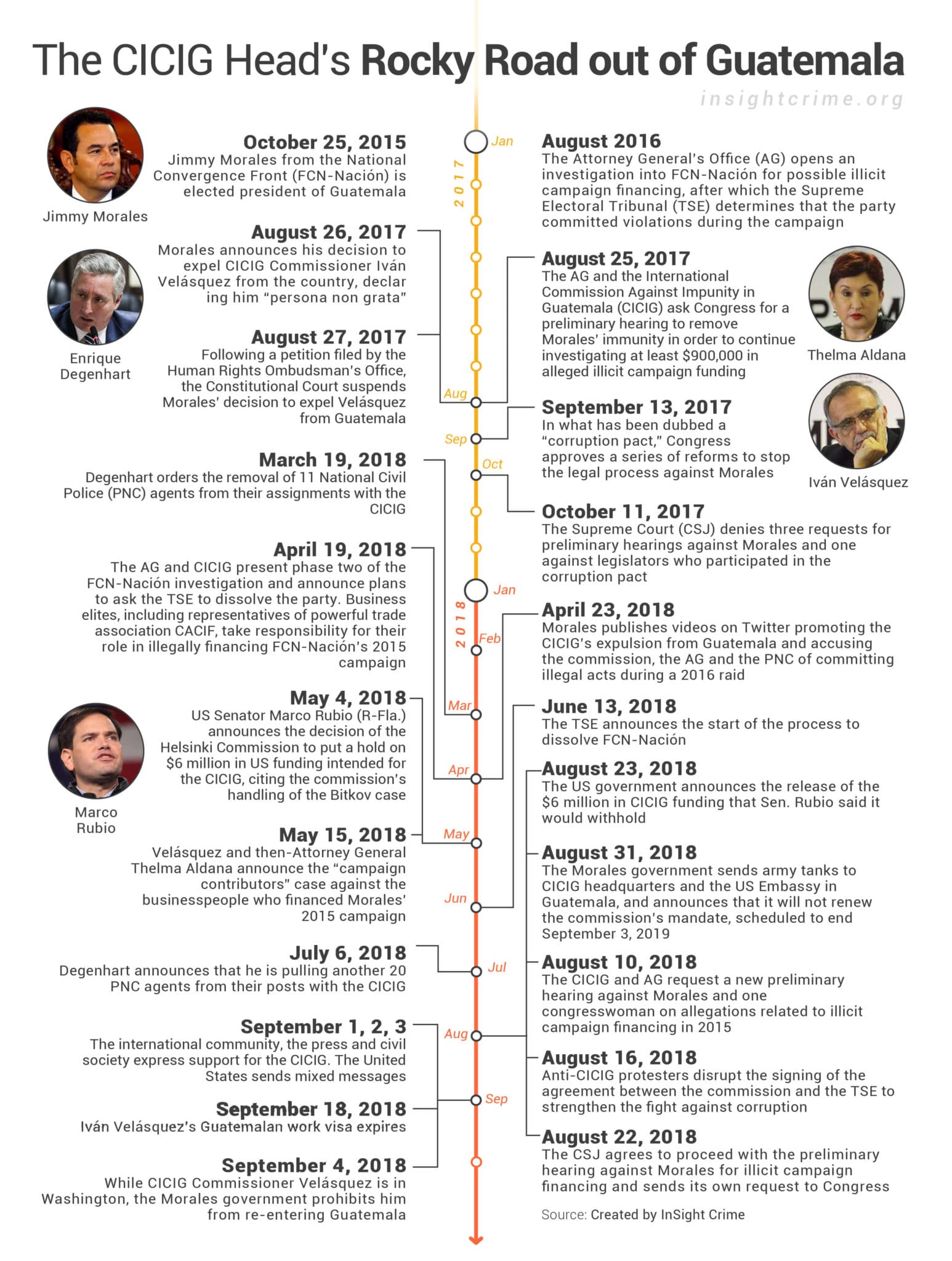

August saw the battle between Morales and the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (Comisión Internacional Contra la Impunidad en Guatemala – CICIG) reach a boiling point. Morales was furious about the CICIG’s investigation into his victorious 2015 presidential campaign.

As InSight Crime reported in a special investigation on the Guatemalan president’s alleged illicit campaign financing, Morales’ dominance — and his rise to the presidency in 2015 — rests on his alliance with powerful ex-military officials, evangelicals and business leaders, groups which have traditionally held sway over the country. Perhaps not coincidentally, the investigations that the CICIG and the Attorney General’s Office conducted wound up identifying representatives from all such groups as suspects.

Of course, such actions are not found in Guatemala alone. Elites have also been closing ranks after coming under fire in El Salvador and Honduras, the other two Central American nations that make up what is called the Northern Triangle.

The Honduran government is being criticized after the leader of its internationally-backed anti-graft body resigned. Meanwhile, in El Salvador the prevalence of political mafias on both the right and the left has stifled incipient anti-corruption efforts in the Attorney General’s Office and the Supreme Court.

Long gone is the enthusiasm that had been awakened in the three countries in previous years for judicial processes and criminal investigations against ex-presidents and businesspeople entangled in complex webs of corruption. The struggles against corruption have not died out, but they will end the year weaker than they started it.

Corruption: Guatemala’s Political Hallmark

If Morales has an opponent in the corruption battle, it is Iván Velásquez, a Colombian judge and the current head of the CICIG, the judicial body backed by the United Nations that has been assisting the Attorney General’s Office in investigating and bringing corruption cases to court. At the beginning of the year, Velásquez told InSight Crime that Morales’ alleged illicit campaign financing is the original sin of the corruption plaguing Guatemalan politics. Then he set out to prove it.

Over the past two years, the CICIG and the Attorney General’s Office have upended Guatemalan politics by revealing connections that the now defunct Patriot Party (Partido Patriota) and Morales’ FCN-Nación party maintained with corrupt businessmen and politicians, who have hijacked and defrauded the government for decades. The investigations also revealed the role the country’s traditional economic elites played in these schemes.

Former president and capital city mayor Álvaro Arzú joined the current president’s efforts to discredit and besiege the CICIG. Morales also attempted to prevent the cases against him from moving past the investigation stage by selecting a new attorney general known to be in line with his interests.

However, not everything turned out the way Morales planned. Arzú died in April, and on August 10, newly selected Attorney General Consuelo Porras requested a new preliminary hearing against Morales for his alleged illicit campaign financing.

Events culminated in August with both Velásquez and Morales surrounded by soldiers. In the case of the former, they had arrived at the CICIG with the goal of escorting the commissioner out of the country, but he ended up staying. For Morales, the soldiers were present at his announcement that he would not renew the CICIG’s mandate, which ended in September 2019.

Morales then seized an opportunity when Velásquez visited the United States in search of further anti-corruption support, ordering his government to bar him from reentering Guatemala.

The country’s Constitutional Court in turn ordered the president not to prevent Velásquez from reentry, but the commissioner has avoided returning to Guatemala for the time being. Even so, the Morales government remains defiant of the court order and insists Velásquez will not be allowed to return to Guatemala.

In late December, Guatemalan officials further tightened the noose around the CICIG, announcing that 11 of its investigators, including some involved in the probe of the president, would not have their visas renewed. That decision left open the possibility that the investigators would be expelled from the country.

While the CICIG and the Attorney General’s Office continue to open corruption cases against local officials, the country’s fight against graft has lost some of the momentum it gained in 2015. At that time, investigations led to a cascade of judicial and political events that kept the government of then-President Otto Pérez Molina in check and eventually put the former president behind bars, where he awaits trial for corruption.

Honduras: Glass Half Full

The event that may best encapsulate the effect of the Honduran political elites’ reluctance to submit to investigations is the February resignation of Peru’s Juan Jiménez Mayor, who led the Mission Against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (Misión de Apoyo contra la Corrupción y la Impunidad en Honduras – MACCIH).

Jiménez resigned in protest after the government of President Juan Orlando Hernández blocked the work of the international organization. The MACCIH was created in 2016 under the auspices of the Organization of American States (OAS) to assist the Honduran Attorney General’s Office in its efforts against graft.

In his letter of resignation to the OAS secretary general, Jiménez explained that Hernández’s National Party used legislators, judges and other quasi-public agents to embark on an institutional campaign to block legal reforms and criminal proceedings being pursued by the MACCIH and the Attorney General’s Office.

Jiménez accused government officials of using the national sovereignty argument to minimize the mission’s impact, among other issues. He also lamented the lack of support he received from OAS headquarters and its secretary general.

In June, the MACCIH — without Jiménez — and the Attorney General’s Office announced the Pandora case, which accused 38 people including officials from both the National and Liberal parties of diverting some $12 million from Honduras’ treasury. One of the issues involved in the Pandora case is the financing of President Hernández’s campaign.

Initially, Hernández seemed to support the investigation, but only conditionally.

“It is fundamental that justice be done. No one is above the law, but at the same time we should all be seeking the principle of the rule of law, the principle of innocence,” he said

By the end of the year, InSight Crime confirmed that the better part of the Pandora case remained stuck in a quagmire of judicial procedures.

In Honduras — as in Guatemala — national sovereignty and the presumption of innocence became the elites’ go-to arguments in their opposition to anti-impunity efforts embodied by organizations like the MACCIH and the CICIG.

It seems no accident, for example, that Hernández was the only president to support the actions of his Guatemalan counterpart at the UN General Assembly in September, when Morales accused the CICIG of “judicial terrorism” and of damaging the country’s sovereignty.

El Salvador: Individuals Sentenced, but Schemes Remain Intact

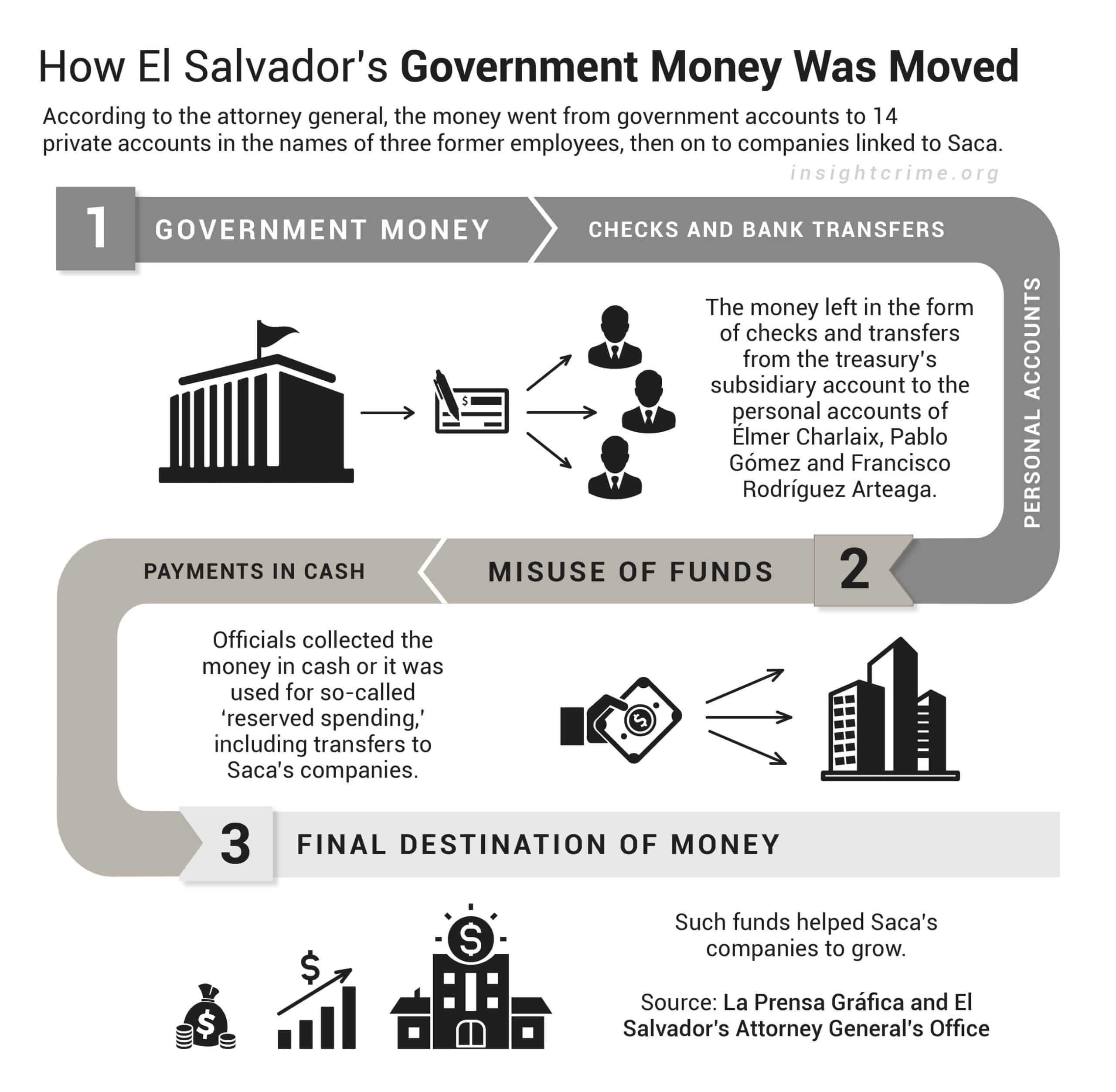

There is some good news to be had this year. September saw the sentencing of former Salvadoran President Antonio Saca to ten years in prison for corruption and bribery. The Attorney General’s Office brought charges against Saca for stealing some $300 million in public funds during his 2004-2009 term. Moreover, after a 2-year investigation, Saca finally gave a confession that implicated not only his own administration in the pilfering of funds, but also the administrations of his predecessor and his successor.

However, the case against Saca is a bittersweet victory for El Salvador. While it marks the first sentencing of a former head of state in the country, the 10 years behind bars that the Attorney General sought is far below the 25 years permitted by law. And Saca’s confession made it clear that the corruption schemes that allowed former Salvadoran presidents to siphon off millions of dollars through a so-called secret fund reserved for the presidency are still intact.

Both the investigation against Saca and another against his successor, former President Mauricio Funes, began with discoveries made by the Supreme Court’s Probity Section, tasked with monitoring the income of public officials. Between 2014 and 2015, the Probity Section opened files on dozens of former presidents, ministers and legislators.

The files could develop into criminal investigations, thanks to a push from the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court, which wrapped up in July. However, the first signals from the new court, elected in November, are not good. It has already said that the investigations about possible misuse of public funds will be kept confidential.

The Ever-Simmering Triangle

When considering the state of the Northern Triangle at the end of 2018, it is hard not to be conflicted. Despite onslaughts from political and economic elites, the anti-graft agenda is holding strong in some government institutions — above all, attorneys general offices — as well as in important sectors of civil society and two international judicial bodies that provide significant global support.

It is undeniable, however, that the region’s elites have gained ground in their attempts to stop the anti-corruption and anti-impunity efforts targeting them. With that, the Northern Triangle’s old woes have returned to center stage.

It is clear that the main objective of the region’s powerful elites is to maintain the control they need over public institutions to evade criminal investigations and prosecution. Unfortunately, this means diverting anti-graft resources from their intended purpose and towards political gains, as in Guatemala; scrimping on anti-corruption efforts, like in Honduras; or even joining the forces of two opposing parties, as in El Salvador.

Credit: AP Images