While traditional criminal organizations have widened their portfolios dramatically in recent years, drug trafficking remains the most important earner in the region. And with opioid consumption surging and cocaine production at a record high, the underworld is reaping the rewards and reshaping itself to fit the times.

The biggest opium source nations in Latin America continue to be Mexico and Colombia, and to a much lesser extent, Guatemala. The opioid epidemic in the United States has been a shot in the arm for organized crime south of the US border, and a new player — fentanyl — has entered the portfolios of some of the most prominent criminal networks.

Mexico is now handily the main source of heroin in the United States, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), which tells InSight Crime that 90 percent of the heroin found in the US comes from Mexico.

The amount of hectares dedicated to poppy plants in Mexico has skyrocketed in recent years, according to the DEA, which says poppy cultivation reached a record high of 44,100 hectares in 2017, up from 32,000 in 2016. Estimated production of heroin increased to 111 metric tons — a jump of more than 300 percent from the amount estimated in 2013 (26 metric tons). Figures from the Mexican government in 2017 reported 24,800 hectares of illicit poppy crops between July 2014 and June 2015, but Mexico has yet to publish similar figures for the 2015 – 2016 period.

The Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco Cartel New Generation are the biggest operators in heroin production, as well as the Guerrero-based Guerreros Unidos and Los Rojos, two splinter groups that emerged from the now mostly fragmented Beltran Leyva Organization (BLO). They also serve to transport heroin, and rely on partners including the Juarez Cartel and the Gulf Cartel to help move it across the central or eastern parts of the US – Mexico border rather than the Southwest corridor, where the majority of heroin is trafficked.

Other regional poppy producers cannot keep pace with Mexico. An estimated 1,000 hectares of opium poppy were under cultivation in Colombia in 2015, enough to produce about three metric tons of pure heroin, according to US Government figures quoted in the 2017 National Drug Threat Assessment. Guatemala’s role is hard to assess, but it is the least significant among the producers. Figures from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime suggest that its share of poppy production dropped between 2014 (640 hectares) and 2015 (260 hectares), but then rose again in 2016, to 310 hectares.

Demand from the United States is the main reason for the Mexican surge in production. Users addicted to pharmaceutical prescription painkillers have been switching to Mexican heroin and the more-deadly synthetic drug fentanyl.

Overdose deaths from heroin increased slightly in 2017, according to U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data analyzed by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The number of deaths, however, from synthetic opioid overdoses has grown at a staggering pace — from around 10,000 in 2015 to nearly 30,000 in 2017, a surge of nearly 200 percent. Synthetic opioids now kill far more Americans than any other kind of drug.

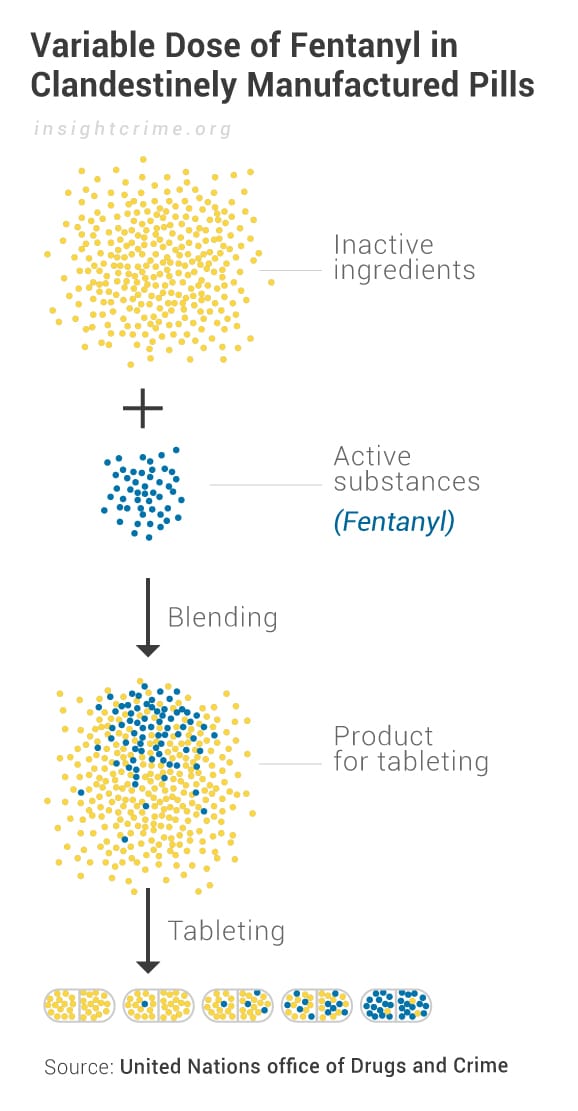

Fentanyl — which is mainly sourced from China either ready-made or via the import of precursor chemicals — is being laced into other drugs such as heroin and cocaine by Mexican groups, and also being moved across the border as a standalone product. In some smaller US markets, standalone fentanyl has supplanted heroin, according to InSight Crime research and media reports, but the drug is mainly mixed with other illegal substances.

It is not known what proportion of illicit fentanyl (a legal form is also produced by pharmaceutical companies) consumed in the United States comes through Mexico. A steady flow of very pure fentanyl reaches users in the United States who purchase it on the dark web and receive it in small quantities from China by mail and courier services.

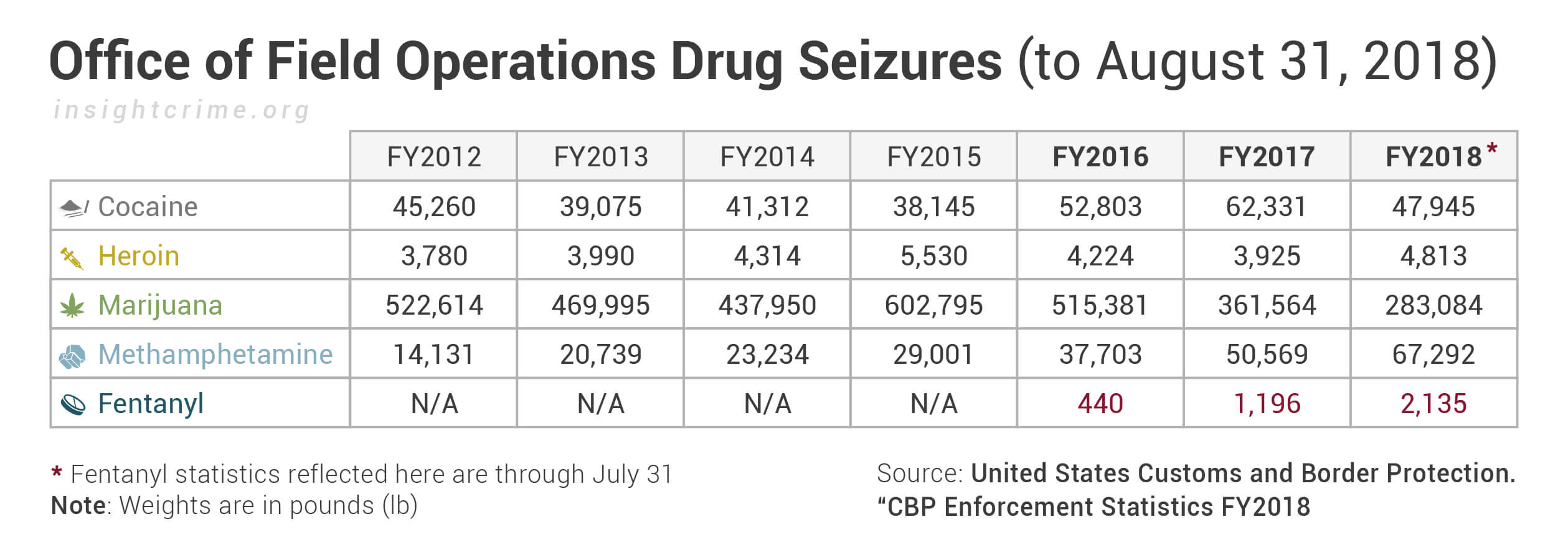

Fentanyl seizures in Mexico have increased in the last several years, according to data in documents attained by InSight Crime following a Freedom of Information Act request. And for groups such as the Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco Cartel New Generation — which have existing networks and supply chains in China for their methamphetamine business — it seems like an obvious lateral move.

A DEA analysis of fentanyl profitability found that one kilogram of heroin stands to net a cartel around $80,000, while a kilogram of 99 percent pure fentanyl could net anywhere between $1,280,000 and $1,920,000. (It’s important to note that most fentanyl brought in from Mexico is seven percent pure on average, while fentanyl brought in from China via the direct mail route is more than 90 percent pure.)

The fentanyl market may also be cutting into the heroin trade. Anecdotal reports suggest that there has been a drop in the price of a kilo of opium paste in the Mexican mountains, from some 18,000 pesos ($900) to around 8,000 pesos ($400), according to interviews with analysts and media reports.

Fentanyl is still not a huge market for Mexican criminal groups. But that could be set to change if demand and consumption in the United States continues to rise. What’s more, Mexican groups seem to be adjusting already to the consumers in this burgeoning market. As of late 2018, most of the fentanyl seizures along the US – Mexico border were laced into counterfeit prescription pills.

In Colombia, meanwhile, the amount of land used for coca cultivation has hit an all-time high, allowing cocaine traffickers to further penetrate new markets, including in Asia and Africa, while continuing to feed demand in the US and Europe. Coca cultivation reached a record 209,000 hectares in 2017, a jump of 11 percent from the previous year’s record of 188,000 hectares, according to the U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy. What’s more, law enforcement officials estimated that pure cocaine production in Colombia increased 19 percent between 2016 and 2017, from 772 metric tons to 921.

This trend marks a reversal from the early part of the decade, when Colombia saw land dedicated to coca cultivation fall, forcing criminal groups to resort to buying coca paste in Peru, which had overtaken Colombia as the top spot for cultivation. In 2012, coca in Colombia had dropped to 48,000 acres, a fourth of what it is today, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). But it began ticking back up in 2013, and has jumped every year since then. Colombia now accounts for 70 percent of the land used for illegal coca worldwide, according to the latest UNODC World Drug Report.

The reasons behind the spike are twofold: Ending aerial fumigation has hampered coca eradication, while an unintended consequence of the ongoing peace process with Colombia’s largest guerrilla group has been more space and opportunity for coca cultivation to flourish.

When talks started between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC) in 2013, the guerrillas controlled over 60 percent of the coca crop in the country. Sensing that the peace process was likely to go forward, the rebels ramped up cocaine production, seeing a last opportunity to generate as much cash as possible before becoming a legal political entity. They convinced farmers in coca growing regions that sowing the crop would give them greater leverage when negotiating for resources from the government, according to InSight Crime research. The coca plants from that time would have matured in the past two or three years.

Additionally, the Colombian government ceased aerial fumigation of coca in 2015 after mounting evidence showed that spraying glyphosate chemicals was harmful to human health. The end of fumigation meant less risk to farmers growing coca, and criminal groups took advantage. In 2012, 100,000 hectares were destroyed through aerial spraying, and 30,000 more were eradicated manually, according to the UNODC’s 2013 report. In 2017, just 52,000 hectares of coca were destroyed on the ground.

Colombia’s newly elected president, Iván Duque, has said he wants to bring back aerial fumigation using different chemicals and targeting fields more precisely with drones. At the same time, Colombia’s crop substitution program, which was implemented after the signing of the 2016 peace accords, has been beset by limited resources, difficulty accessing rural communities where security is lacking, and mistrust from local farmers who say they have yet to see real benefits.

Soldiers eliminating coca crops have met increased resistance from communities. In 2018 confrontations between growers and the government turned deadly in Tumaco, a southwestern port city in the department of Nariño where a large share of the nation’s coca is now produced. In the city of Cúcuta, which borders Venezuela, protesters barricaded roads and managed to get authorities there to suspend eradication efforts, El Tiempo reported.

The FARC’s disarmament and demobilization also left a power vacuum in coca growing regions. This has led to an uptick in violence. The group’s dissident members, and the country’s two remaining rebel forces — National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional – ELN) and Popular Liberation Army (Ejército Popular de Liberación – EPL), both of which had previously been lesser players in the cocaine trade — have fought to take control of these areas. The groups have also battled with established traffickers for control of smuggling routes.

But the bloody wars of previous decades, in which guerrillas battled paramilitary groups and cartels fought one another, seem to be over. Cooperating in the cocaine trade are criminals of all stripes: various guerrilla factions; the ex-paramilitaries that form the BACRIM (“bandas criminales”); and traditional traffickers like the Urabeños, Colombia’s strongest criminal organization.

US Law enforcement officials report that the Urabeños regularly send multiple tons of cocaine to nearby Panama and other countries in Central America by go-fast boats. But the Urabeños’ structure differs from that of the top-down cartels in Colombia’s past, acting more like a network of independent nodes.

Flamboyant capos in the mold of Pablo Escobar have vanished. Today’s traffickers at the center of Colombia’s cocaine trade are largely invisible, preferring to never touch a kilo of cocaine and pass for ordinary businessmen. For them, security comes from anonymity. Yet all the recent transfigurations of Colombia’s traffickers haven’t diminished their power, and may have even spurred their expansion as transnational criminal organizations.

In South America, Colombia is not alone in seeing an increase of cocaine production. In Peru, pure cocaine increased by 20 percent, hitting 491 metric tons, the highest levels recorded in 25 years, according to the Office of National Drug Control Policy.

The boom in cocaine and the ease with which the drug is moving through various South American countries has also opened new smuggling routes. For example, the cocaine transiting Venezuela is then moved to the Dominican Republic. The Caribbean country has been identified as a primary source of cocaine destined for Europe.

Europe as a whole has increasingly become a destination for cocaine, and the amount seized there jumped 11 percent in 2016, according to UNODC’s 2018 World Drug Report. Marked increases were reported in Southeastern Europe, where the quantity of cocaine seized more than tripled in 2016 when compared to the previous year. For the first time, Belgium seized the most cocaine, followed by Spain and the Netherlands.

The explosion in cocaine production has also allowed traffickers to further penetrate emerging markets in Africa and Asia. Though the quantity of cocaine seized there pales in comparison to Europe or the Americas, these regions saw some of the largest jumps in seizure amounts. In Africa cocaine seizures doubled, and the North African countries reported a six fold jump from 2015 to 2016. Africa has increasingly served as a transit hub for cocaine moving through Brazil that ends up in Europe.

Brazil is also the departure point for cocaine destined for Asia, where the amount of cocaine seized tripled. Much of that cocaine transited the United Arab Emirates. China, including Hong Kong, was cited most frequently as the primary destination country, followed by Israel.

But the United States remains the destination for the vast majority of cocaine. As it is with opioids, the US numbers are worrying. Nationwide seizures of cocaine have hit their highest level since at least 2010, reaching 34,000 kilograms in 2017, a 40 percent increase over 2016, according to the DEA. About 93 percent of cocaine samples tested in the US were of Colombian origin.

The cocaine boom has also seemingly led to an increase in the drugs use in the United States over the past three years, according to reports from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Most troubling, nearly 15,000 people died from overdoses involving cocaine in 2017, more than double the amount of people who died in 2015.

Among illicit drugs, cocaine trails only opioids as a killer.

Credit: AP Images