Corruption scandals have continued to break at dizzying pace across Latin America throughout 2017, spanning politics, business, the security forces, the judiciary and even sports teams. But while the revelations have been exposing the rotten core of Latin America’s ruling class, entrenched elites are now fighting back in what could prove a pivotal battle for the future of the region.

There was barely a corner of Latin American life that was not touched by corruption scandals in 2017.

The richest source of revelations of just how far reaching and systematic corruption is in the region was the investigation into Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht and its business model of using mass bribery to secure lucrative contracts.

Over the course of the year, InSight Crime reported how this investigation has now implicated Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto, Ecuadorean Vice President Jorge Glas, Peruvian presidential candidate Keiko Fujimori, former Peruvian President Alejandro Toledo, Venezuelan political leader Diosdado Caballo, a string of officials in the Dominican Republic, and even the now former guerrillas of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC). And investigators have promised that more is to come.

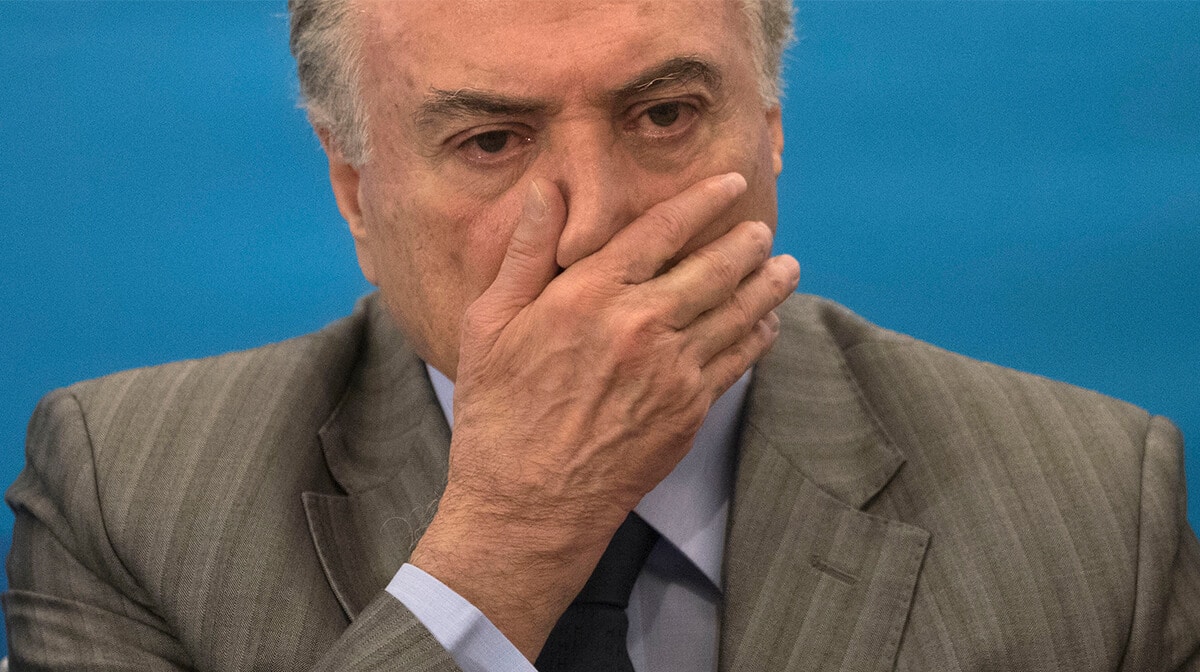

The year also saw the continuation of a trend of corruption investigations reaching ever higher up the political power chain. El Salvador’s former President Mauricio Funes and Brazilian ex-President Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva were both convicted on corruption charges. Lula’s deposed successor Dilma Rousseff was indicted for corruption and money laundering, current Brazilian President Michel Temer was charged with obstruction of justice and racketeering, Panama’s former President Ricardo Martinelli was arrested on espionage charges in the United States, and Argentina’s last leader Cristina Fernández de Kirchner was indicted for money laundering.

Revelations detailing how corruption networks interact with organized crime to facilitate drug trafficking and money laundering have also emerged at a frantic pace. This has especially been the case in the Northern Triangle, where testifying drug lords and US investigators — along with InSight Crime’s extensive special investigations — have uncovered collusion that stretches from the municipal mayors to the upper echelons of political and economic power.

In Colombia, meanwhile, investigators have begun to expose another key sector for corruption in the region: justice systems. An investigation that began with the arrest of the country’s former anti-corruption chief continues to unravel at a breakneck pace, and has already exposed how the country’s Supreme Court was itself allegedly a key node in corruption networks that sabotaged the prosecutions of underworld chiefs.

Not even the sacred Latin American field of sport has emerged unscathed from 2017’s anti-corruption campaigns. In November, InSight Crime reported on the start of the corruption trials of regional soccer officials as well as a string of new indictments and allegations over the role of media companies. The following month, the head of Brazil’s Olympic committee was detained on bribery charges.

This trend has been evident in everything from threats and intimidation of Panamanian prosecutors working on corruption cases to Paraguayan politicians attempting to hollow out laws targeting criminal money corrupting campaign financing. However, the most evident pushback has come in the two countries where anti-corruption investigations have made significant headway: Guatemala and Brazil.

In Guatemala, evidence continued to emerge of the rampant corruption and criminal ties of the previous administration of President Otto Pérez Molina, who was removed from office and imprisoned in 2016 along with his Vice President Roxana Baldetti and several other key political allies. However, the anti-graft campaign did not stop there, as the international body behind the investigation, the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (Comisión Internacional contra la Impunidad en Guatemala – CICIG) turned its sights not only on Pérez Molina’s successor Jimmy Morales, but also the country’s two main opposition parties.

First to fight back was President Morales, who has faced mounting accusations of corrupt campaign financing and ties to drug traffickers since winning the presidency on an anti-corruption platform. In August, Morales declared the Colombian head of the CICIG, Ivan Velázquez, persona non grata. Although his efforts to remove Velásquez from the country were frustrated by the courts, Morales was able to secure immunity from prosecution in a congressional vote.

SEE ALSO: Guatemala Elites and Organized Crime

When the CICIG then turned its sights on other politicians, it managed to mobilize the country’s entire political elite against them. This culminated in a vote to reform a law in order to protect politicians and their party functionaries from prosecution and penalties in cases of illicit financing of political campaigns.

As we pointed out at the time, the CICIG had “effectively cemented a political alliance among these former foes, incentivizing them to create blanket protections for the rest of the parties and their corrupt operatives and leaders.” With the new law, we added, “congress and the president have institutionalized corruption in the political process.”

As in Guatemala, Brazil’s far-reaching corruption investigations exposed the breath taking scale of graft in the country. But these efforts have similarly run into fierce opposition.

The Brazilian congress — many of whose members have been accused of corruption — voted twice to spare Temer from standing trial on the criminal charges against him. The votes, however, seemed to be part of a broader strategy to undermine anti-graft initiatives. Earlier in the year, the government took a far more insidious route, by slashing funding and staffing for Operation Car Wash.

The moves seemed to confirm our expectation from earlier in the year that “the significant expansion of the corruption probe could unite Brazil’s typically fractious political landscape around the goal of derailing the investigations.”

Anti-corruption efforts retain significant popular support in the region, but the elite backlash has cast doubt on whether they can be sustained. The conflict between these two powerful forces could be decisive for whether Latin America can finally address chronic issues of poverty, inequality and rampant organized crime.

The truth of the region’s systemic corruption has been forced out into the open. What remains to be seen is what can be done about it.

Top photo by Associated Press/Leo Correa