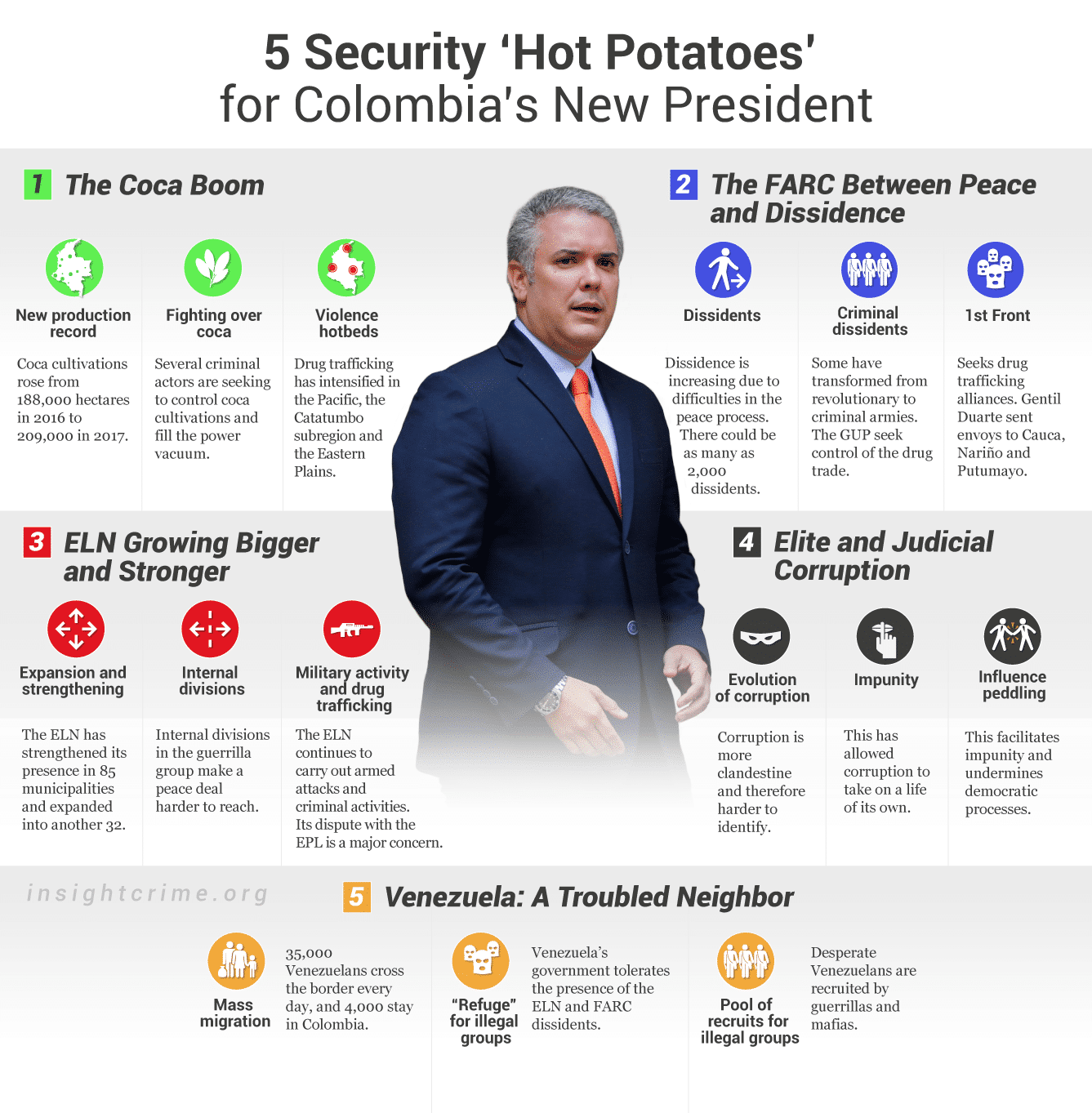

Colombia’s new President Iván Duque took office August 7 where he will have to face down an ever-evolving underworld.

The list is long: drug trafficking driven by a record increase in the number of coca crops and the implementation of a historic peace agreement are some of the key battles; the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional – ELN), the last remaining protagonist with a national presence; a country steeped in corruption; political, social and economic instability of Venezuela, Colombia’s troubled and troubling neighbor.

Here are five hot potatoes Duque will face in office.

(Click the graphic to enlarge)

1. The Coca Boom

Colombia now produces more cocaine today than ever after producing a record 921 metric tons of the drug in 2017. Cocaine production in the country was on the decline until 2012, but by 2017 the country was producing 209,000 hectares of coca crops, an 11 percent increase from the 188,000 hectares produced the year before, according to official figures from the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP).

The numbers show that the cocaine trade has mutated yet again, finding new and more lucrative forms and destinations. These changes are related to shifts in criminal structures that are now more fragmented, networked and efficient.

This is also due to the existence of a new generation of drug traffickers who seek to obtain greater profits without having the reflective lights of authorities on them. To achieve this, they have become invisible. They no longer seek to surround themselves with large private armies. These negotiators have specific knowledge of world markets that allows them to mix licit and illicit activities in a highly sophisticated manner.

SEE ALSO: The ‘Invisibles’: Colombia’s New Generation of Drug Traffickers

It’s also a period of transition. Amid the departure of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC) from the criminal landscape, new criminal actors control these illicit crops. The battles for former FARC-strongholds and fertile coca crops has slowed efforts to eradicate coca and in some cases delayed crop-substitution programs outlined in the 2016 peace agreement between the FARC rebels and the Colombian government.

The outgoing administration of Juan Manuel Santos committed to eradicating 180,000 hectares of illicit crops by 2023, a total of 36,000 hectares per year. As it stands, President Duque still has 80 percent of this plan he must implement to fulfill this promise.

Duque has an advantage over his predecessor in that he has the backing of the United States to implement aerial fumigation programs, and he supports these programs with some caveats.

“[Aerial] fumigation must be resumed, but with chemicals that are authorized in Colombia, eliminating any third-party risk and taking advantage of precision techniques that allow us to be more forceful. You have to combine all the tools and you cannot give any of them up,” Duque said in comments to El Tiempo.

According to field research conducted by InSight Crime, drug trafficking has intensified the most in Colombia’s Pacific Coast, the Catatumbo and Eastern Plains regions near the Venezuelan border and the Putumayo department on the Ecuadorean border.

2. A Shaky Peace Process and FARC Dissidence

During his first speech as president-elect, Duque pointed out that he would seek to maintain the agreement while making some modifications. His position has generated public concern, especially among the largely demobilized former rebels.

But things are already falling apart: complaints about the murder of demobilized FARC members; legal insecurities highlighted in the case against Seuxis Paucis Hernández Solarte, alias “Jesús Santrich“; the refusal of the accords’ main negotiator, Iván Márquez, to assume his Senate seat; the capture of one of the most powerful FARC dissidents, Luis Eduardo Carvajal Pérez, alias “Rambo”; the troubled programs to reintegrate former guerrillas and the failing crop substitution programs noted above. It is a formula for a rise of dissident groups.

In fact, there are more demobilized fighters who abandon the peace process and swell the ranks of dissident groups each day. InSight Crime field research indicates that as many as 2,000 have already joined old and new criminal organizations.

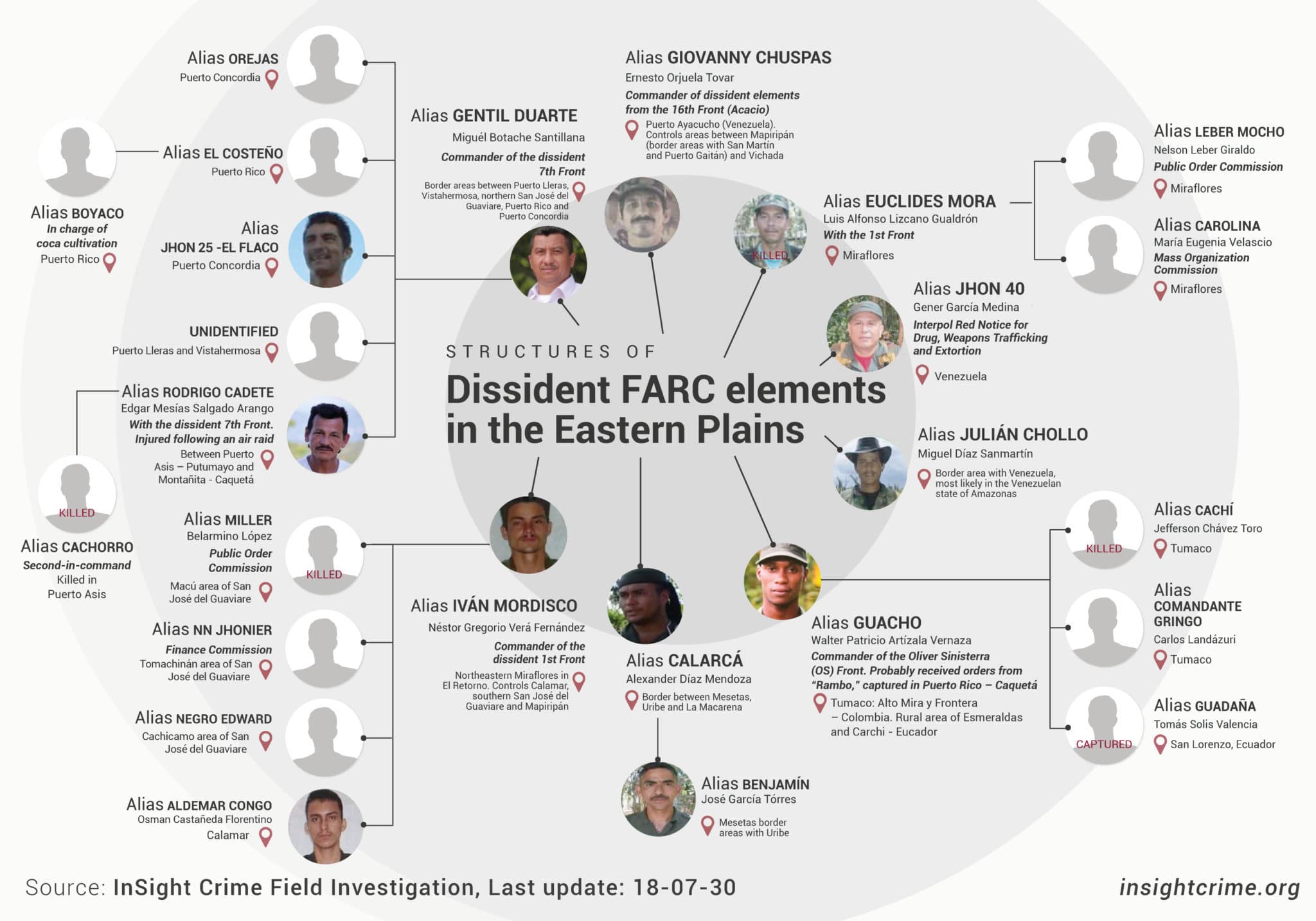

To be sure, few dissidents retain their identity as a revolutionary army. Since the 1st Front declared itself a dissident group, various other former rebel factions have formed a loose criminal network that is organized around the drug trade.

(Click the graphic to enlarge)

Miguel Botache Santillana, alias “Gentil Duarte,” one of the most visible dissident leaders, has even sent ex-FARC representatives to southwestern Cauca, Nariño and Putumayo departments. This has helped him coordinate with other dissidents like Walter Arizala Vernaza, alias “Guacho.” While Guacho’s criminal days may be numbered, he has managed to configure his Oliver Sinisterra Front as one of the main criminal actors operating along the Colombia-Ecuador border.

What we call the ex-FARC mafia may be the main criminal group that Duque will face. It is made up of dissidents and former FARC members who, although they did not declare themselves dissidents, distanced themselves from the peace process and continued taking part in criminal activities.

Another factor to take into account is the increased presence of representatives from Mexico’s criminal groups who seek intermediaries to guarantee the continued flow of cocaine in the wake of the FARC’s departure. As a result, the ex-FARC mafia has gained greater prominence because they are the most consolidated criminal actor in the areas where coca production is the highest.

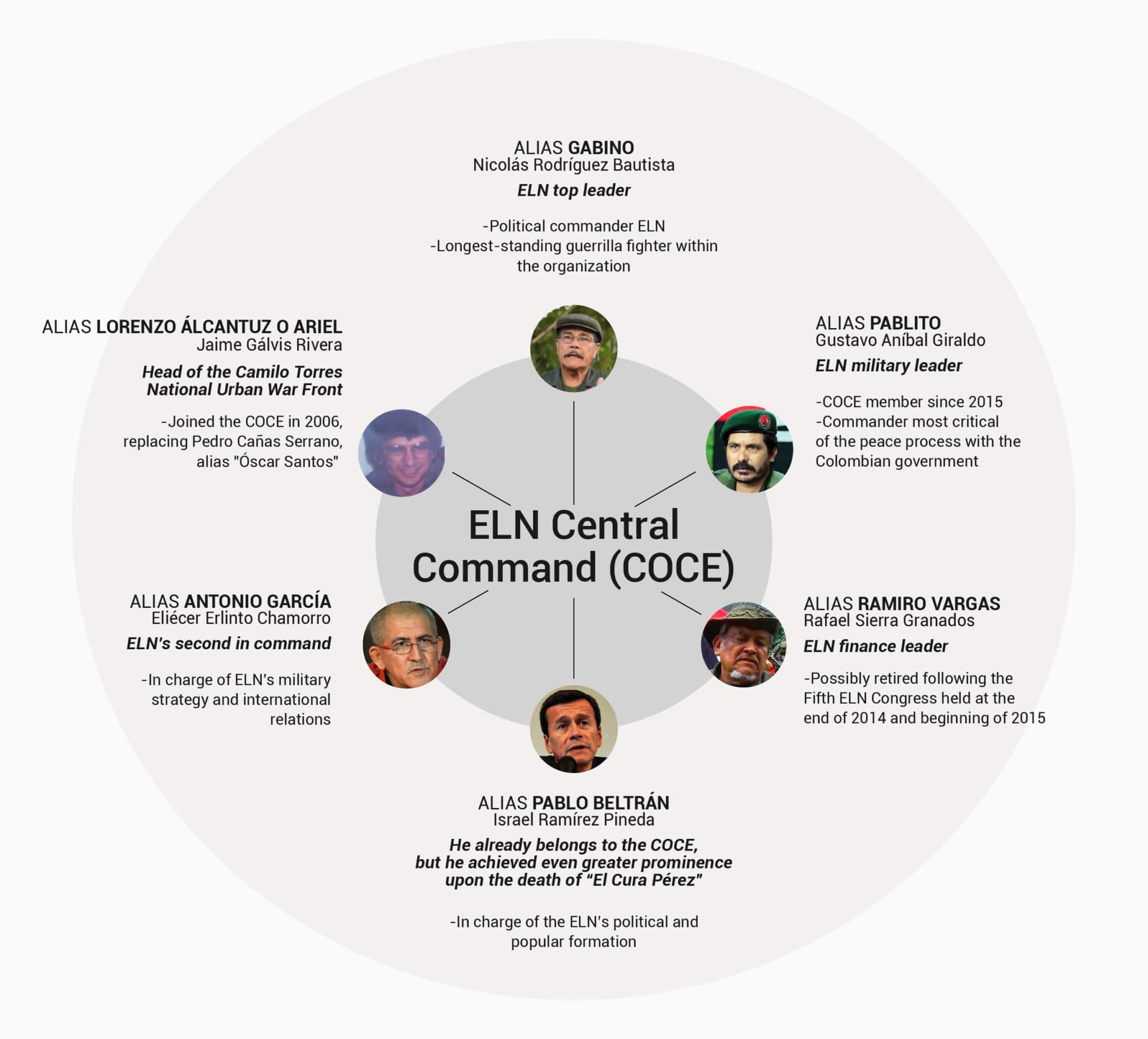

3. The ELN’s Unchecked Expansion

With the demobilization of the FARC, it was almost natural that what they left behind was taken over by what is now Colombia’s most important guerrilla group: the ELN. Between 2017 and 2018 — after the signing of the 2016 peace agreement with the FARC — InSight Crime identified 85 municipalities in Colombia where the group got stronger and another 32 where they sought to expand. The most aggressive ELN fronts included Guerra Occidental, Oriental, and the Darío de Jesús Ramírez Castro.

One of the main factors that could explain this territorial expansion is the active participation of these ELN structures in the drug trade. “Uriel,” a spokesman for the Guerra Occidental, highlighted the group’s strategy recently in an interview.

“We collect taxes from the drug trafficking business wherever the Omar Gómez Guerra Occidental Front operates,” the guerrilla said.

(Click the graphic to enlarge)

The statement illustrates a continuing divide in the ELN. As part of the peace talks with the government, the ELN’s Central Command (Comando Central – COCE) has said the group does not have links with the drug trade. However, other parts of the ELN are skeptical about the negotiations; these groups have paused their military and political plans, but not their economic plans.

For his part, Duque sent a strong message to the guerrillas, laying out his conditions for ongoing negotiations.

“Here, the only way to build what gives confidence to the Colombian people should be about the suspension of all criminal activities, and the best way to proceed in this matter should be through a meeting with international supervision that defines a supremely clear time and allows us to look at what the elements for that transition may be, which may involve a substantial reduction of penalties, but not the absence of them,” Duque said.

In the short term, the negotiations with the ELN will be maintained as a result of international pressure and the intentions expressed by ELN spokespersons to move forward and resolve the “Red Points.” However, as the military operations, criminal activities and territorial expansion of the ELN continue, it is likely that negotiations will be delayed further and that the guerrillas will continue to spread.

Meanwhile, it remains to be seen if the ELN will have the capacity to maintain territorial control of the areas it has taken over, and prevent groups like the Popular Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Popular – EPL) and the ex-FARC mafia from snatching control of the drug trade.

4. Invisible and Widespread Corruption

Duque faces an even greater challenge: to attack the corruption undermining Colombia’s institutions and its democracy.

Corruption today is perhaps more sophisticated than ever. Years of collusion with criminal actors has led some government officials to establish their own criminal organizations within state institutions.

This was evident in one of the biggest corruption scandals to ever hit the government. The Cartel de la Toga was a corruption network uncovered within the Supreme Court in mid-2017, when the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) helped Colombian authorities capture Luis Gustavo Moreno, the prosecutor in charge of the main investigations into corruption in Colombia. The lawyer was the key node in a network of massive bribes paid to investigators and the Supreme Court’s president in exchange for legal benefits. The network undermined investigations into, for example, congressmen who had been connected to paramilitaries.

(Click the graphic to enlarge)

Toga showed how corruption has grown increasingly sophisticated. With all three branches of government involved, impunity was virtually guaranteed and corruption harder to find.

Indeed, there is almost a pre-established system, a playbook that these actors follow. The result is that they accumulate more power and can eventually create a portfolio of services leading to even more corruption.

Corruption also undermines regional and local governments, which is undermining peace initiatives and demobilization efforts. In some instances, corruption is seen as a legitimate way to build consensus and make government work, especially in regions where local political actors and criminal actors intermingle.

On a more personal level, Duque must deal with the case against his mentor, former president and current Senator Álvaro Uribe. Uribe, along with his brother Santiago, is being investigated for trying to obstruct justice. In this, Duque faces his own challenge: support the rule of law or face charges of obstructing justice himself.

5. Venezuela: The Troubled Neighbor

The other hot potato that threatens to burn Duque is Colombia’s increasingly tense relationship with its troubled neighbor, Venezuela.

Although both countries share problems — InSight Crime once classified them as criminal Siamese twins — the political differences between their leaders in recent years have made it almost impossible to reach agreements and share strategies to fight the organized crime groups that have developed a symbiotic relationship along the border and beyond.

Political and economic problems in Venezuela have led to rampant migration. More than 35,000 Venezuelans cross the Simón Bolívar Bridge each day to flee the economic and social crisis affecting the country. They mostly arrive in places like eastern Cúcuta in search of food, work, and medical attention; as many as 4,000 of these people stay, most of them moving to other locations, according to Al Jazeera.

SEE ALSO: Venezuela News and Profiles

The mass migration creates a fertile criminal breeding ground and a source of revenue for criminal groups. There are reported cases of human trafficking and human smuggling, prostitution, child abuse and the recruitment of Venezuelans by organized crime.

On June 13, for example, four Venezuelans were killed in the bombing of a FARC dissident camp in Arauca. Their deaths came after Colombia’s government had complained that Venezuelans were filling ex-FARC ranks. According to their relatives, the victims joined the former guerrillas for economic reasons. They said they received payments ranging from 100,000 to 200,000 pesos (between $30 and $60) per month.

The Venezuelan government has also failed to crack down on these criminal groups, something Duque has already noted.

“Today Colombia needs a president to internationally denounce the regime of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, which is providing sanctuary, money, and armament to the ELN,” Duque said during his campaign.

Finally, Venezuela is a key transit country for Colombia cocaine. However, cooperation seems unlikely, especially since top officials in Venezuela have been linked to the drug trade.

“We must act with all the forcefulness of the countries that support the Inter-American Charter to exert diplomatic pressure on the dictatorship,” Duque said in reference to Venezuela during a recent trip to the United States.

Duque has also said that he will denounce President Maduro before the International Criminal Court, according to RCN News.