Colombia’s homicide rate rose for the first time in a decade in 2018, reflecting renewed conflicts between criminal groups in strategic areas of the country in the wake of the demobilization of FARC guerrillas.

The national murder rate in 2018 reached 24 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2018, a slight jump from the previous year’s rate of 23 per 100,000, according to a report by Colombia forensic institute Medicina Legal.

Homicides, however, spiked in the 161 municipalities described as previously being controlled by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC). In these areas, 2,957 homicides were registered in 2018, a 30 percent increase from the 2,271 tallied in 2016, according to the Attorney General’s Office. More than 54 percent of cases were related to disputes between criminal actors.

This marked the first year during which Colombia has seen an increase in violence since peace talks began between the government and the FARC in 2012.

SEE ALSO: Colombia News and Profiles

One year after the peace agreement was signed in 2016, then vice-president Germán Vargas Lleras declared that the country would end 2017 with the lowest homicide rate in four decades.

But in late 2017, Colombia witnessed fresh outbreaks of violence in municipalities that had been abandoned by the FARC and then reoccupied by organized crime groups.

InSight Crime Analysis

Colombia’s rising murder rate in 2018 is a predictable consequence of the territorial disputes that emerged following the FARC’s demobilization. A growing number of FARC dissidents, as well as other rivals jockeying for position, has left areas of Colombia facing a rapidly evolving landscape of criminal alliances and feuds.

The municipalities which have suffered the most from this crisis are representative of these criminal dynamics.

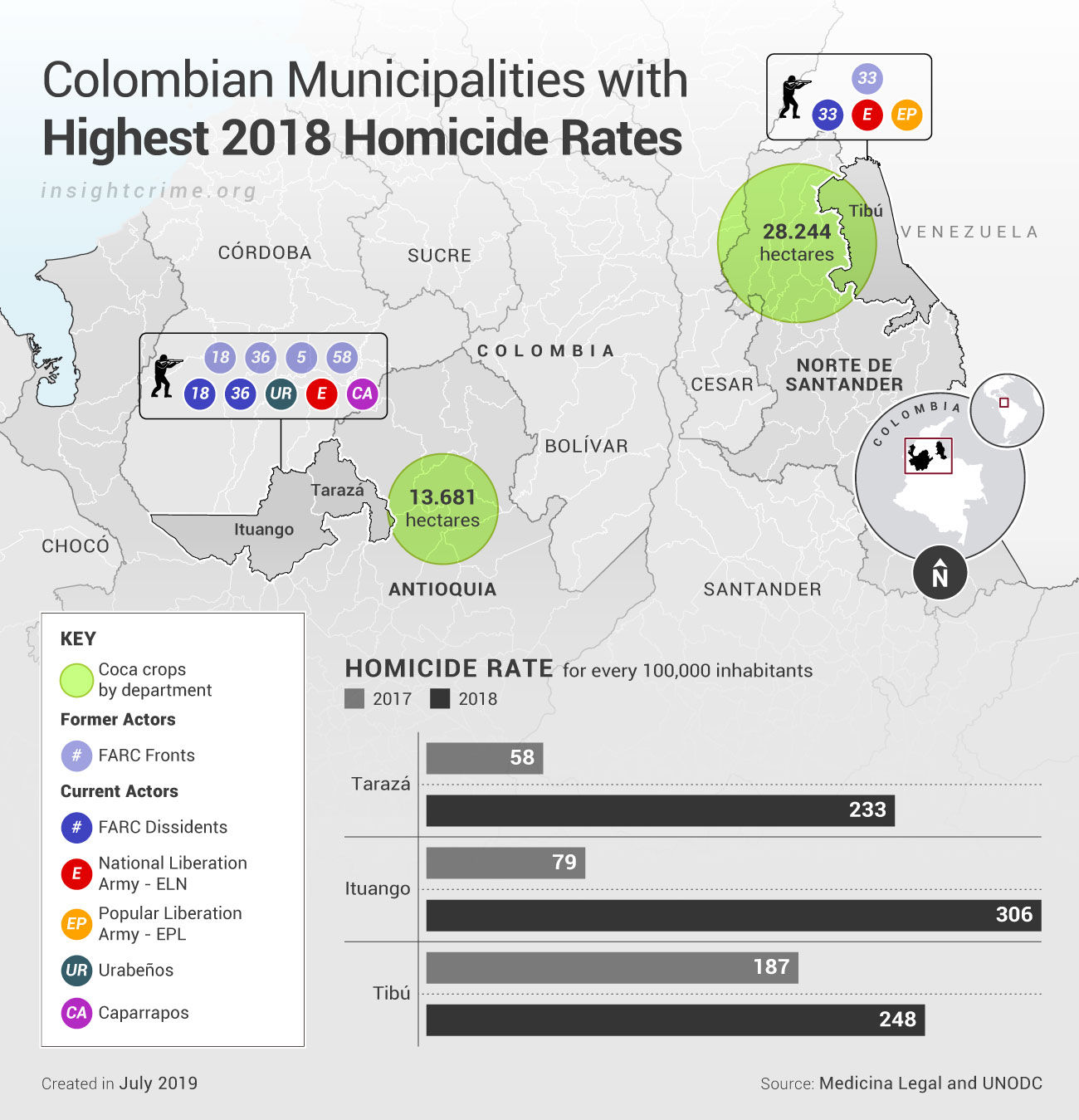

According to the Medicina Legal report, the municipalities with the highest homicide rates in 2018 were Ituango, Tarazá and Tibú. All of these were formerly FARC areas of influence, which counted a number of criminal economies.

SEE ALSO: Is Colombia Underestimating the Scale of FARC Dissidence?

Ituango and Tarazá are located in the department of Antioquia, in northwest Colombia. Statistics from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) show that, in 2017, Antioquia was the department with the fifth-largest coverage of coca crops in the country.

According to the governor of Antioquia, Luis Pérez, between 75 and 80 percent of the state’s coca is concentrated in the subregion of Bajo Cauca, where Ituango and Tarazá are found.

Driving violence in these areas are a number of criminal actors, including drug trafficking groups like the Urabeños and the Caparrapos, and the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional – ELN) guerrilla group. All are fighting for control of coca cultivation and cocaine production.

Between 2017 and 2018, Ituango’s homicide rate rose sharply from 79 to 306 per 100,000 inhabitants, while its number of forced displacement victims rose from 223 to 718 people. The increases in Tarazá were equally striking: from 58 to 233 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants. The number of people displaced jumped from 489 to 2,840, according to Verdad Abierta.

The situation is similar in the municipality of Tibú, in Norte de Santander department along the Colombia-Venezuela border, which had the second-highest area of coca plantations nationwide, according to UNODC data.

Tibú is located in the Catatumbo region, a strategic drug trafficking corridor running towards Venezuela and the Caribbean coast. There, the homicide rate jumped to 248 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2018, up from 187 in 2017. Authorities attribute much of this rise to the conflict between the ELN and Popular Liberation Army (Ejército Popular de Liberación – EPL) guerrillas.

However, some positive news came in the first six months of 2019, during which homicides dropped by six percent when compared to 2018.