The killing of a Texas family on a bus in east Mexico before Christmas remains a mystery; it does not appear that robbery was the central motive and the Zetas were quick to deny responsibility, while the government response only obscured the facts further.

The riddle is as big as Mexico: What really happened to the Hartsells? Sure, this was just one more doomed passenger bus, hit by one more explosion of horror.

But it’s also an emblem — because it’s one more occasion when the real nature of the violence raging through Mexico has remained a baffling mystery.

Consider the sheer range of the unanswered questions:

Was this family savaged because cartel terrorists were sending a national-scale message?

……….Or were these ordinary local robbers, wild on alcohol or drugs?

Was this a conspiracy, reaching out to a whole nation of 113 million people?

……….Or was it simply a small, grisly accident of fate?

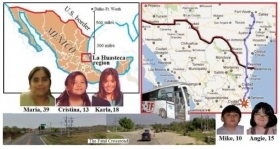

The Hartsell case appears as a pastiche of missing puzzle pieces — the usual mix in Mexico’s time of trials. But there are a few more clues this time, because, unlike local victims of such violence, the Hartsells were US citizens. They were visiting family in Mexico from their home in Cleburne, Texas, near Ft. Worth. They didn’t seem to be targeted because they were Americans, but their status has allowed some pivotal witness accounts to emerge in relative safety, north of the border.

SEE ALSO: Profile of the Zetas

When the resulting clues are pieced together, they don’t point to the most reasonable-sounding explanation, the one saying that ordinary thugs on a Mexican backroad must have gone a little crazy. They point instead toward the crazy conspiracy theory, the great shadow: organized terrorism.

The first puzzle piece was the typical Mexican government announcement — cryptic as a mumble in the dark. On December 22 itself, almost as soon as the crime had gone down, the Mexican Army proudly announced catching a mysterious band of five men, said to be the attackers of that particular Transportes Frontera bus, which was stopped around dawn some 300 miles south of the US border, three days prior to Christmas 2011.

But, the government added solemnly, the five suspects had resisted arrest. They had fired at arriving troops. And so naturally the troops fired back. And the suspects were all killed. And that, said the government, left no way to learn just who these mysterious marauders might possibly have been — or WHY they had gone into a frenzy of killing.

Case closed. By January 3, the Mexican daily El Universal was parsing it like this: “Chief state prosecutor Amadeo Flores Espinosa said it had been determined that the five dead criminals committed the attack on December 22. Therefore, he said, the investigation has been closed and concluded” — though the five suspects were never publicly identified.

Whoever the attackers were, they had required only a few hours to strike not only three separate passenger buses but two cargo vehicles, all on or near Mexican Highway 105, where it backtrails the northern fringe of the Mexican coastal state of Veracruz. The almost frenetic pace of multiple attacks left a trail of carnage stretching well beyond the Hartsell encounter. But like the Hartsells on the Frontera bus, all the victims seemed to share one trait. They were chance bystanders, not drug-war combatants. And — crucially — the scant evidence that has been allowed to surface seems to demonstrate that the central reason for the attacks was not robbery. Any fragmentary statements about robbery in the press seem to have reflected media assumptions, not investigations. But if so, what WAS the motive? Why this merciless rampage?

This part of northern Veracruz lies in a beautiful but notorious region of green foothills called the Huasteca. And the Huasteca, especially in the vicinity of the attacks, is Zeta country. The Zetas cartel could be called Mexico’s most openly terroristic drug trafficking group. Their massacre patterns remind of their origins among miltary deserters. But were the five mystery men Zetas? The lack of firm answers to this question was essentially buried.

A Zeta trademark is the commission of general acts of terror without overt explanation. There are normally no subtitles to explain things like: “This is a message to the public at large, showing what will happen if you don’t knuckle under,” or “This is a message to the government, showing what will happen to your citizens if you anger us.” Instead, gloating silence may alternate with the occasional explicit taunt, adding to public anxiety. But did it happen in this particular case? The Zetas themselves took the trouble to deny it. In a town called Tantoyuca, 30 miles south of the attacks, a public banner appeared on December 27 — the kind of “narco-message” often seen in the drug war. Neatly signed, “Sincerely, Zetas Unit,” it said primly of the bus attacks: We didn’t do it. Even in a labyrinth of liar’s poker, this did mean something. But what?

The Zetas aren’t the only thugs in those hills. Smaller groups of ordinary highwaymen have appeared. In 2010, another government announcement told of another band of mysterious bus hijackers — also five in number — but arrested alive, named, photographed and sent to prison, after the murder of a bus driver and three rapes. And apparently those bus bandits weren’t Zetas. The government said they were escaped convicts. Nor does this exhaust the possibilities. At times, cartel enemies of the Zetas have been known to stage black-flag jobs to make the Zetas look bad. Did it happen here?

SEE ALSO: A Massacre In Mexico: What Really Happened To The Hartsells? Part II

In the festive air of December 21, 2011, the big bus terminal at Reynosa, the metropolis of Mexico’s eastern border, was thronged with ticket buyers. Reynosa’s populous border strip lies some 300 miles north of greener Veracruz, in a different region of Mexico — with different safety dynamics at the end of 2011.

In 2010 and early 2011, the environs of Reynosa had seen so many cartel-war massacres that by mid-year thousands of troops were surged in — enforcing a new period of local peace — nervous, but very welcome. Earlier in 2011 that border area had convulsed as more than a dozen long-distance passenger buses were attacked in bizarre killing sprees — undoubtedly the work of the Zetas Cartel, though here, too, the motives were hauntingly obscure.

In April, bus traffic lay paralyzed, but by August the troops had chased the Zetas away, pushing them into other strongholds — one of which lay 300 miles south in Veracruz. By December, bus company spokesmen in Reynosa were gushing about the Christmas rush, saying enthusiastically that people had found the confidence to travel again. Three million US residents were said to be coming home to Mexico for the holidays.

On December 16, Mexican President Felipe Calderon weighed in with Operation Winter 2011, beefing up holiday highway security across Mexico, assigning 12,000 extra federal police. Calderon was down 20 points in the political polls because of his drug war, fought bravely but disastrously since his inauguration in 2006. His political party, nearing July 2012 elections, badly needed the good news of Christmas peace on the eastern border.

Anyone who ruined this silent night would be striking Calderon a personal, Grinch-like blow.

See Gary Moore’s blog.