The arrest of Seuxis Paucis Hernández Solarte, alias “Jesús Santrich,” has shaken the FARC party, tried the new peace courts, and implicated scores of other underworld figures, including Mexico’s “Narco of Narcos.”

Santrich was detained on April 9 at his home in Bogotá after the United States charged him with drug crimes. He has been one of the foremost figures of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC). He helped negotiate a 2016 peace deal between the government and the rebel group, and he was about to take a seat in Colombia’s congress as a representative of the FARC’s political party.

Here are the four most concerning revelations and repercussions of Santrich’s shocking arrest.

1. Santrich’s network of DEA informants, FARC dissidents and Mexican capos

Two different triggers started the US and Colombian investigations of Santrich, which for some time ran parallel without both sides’ knowledge. The US lead was an alleged drug trafficker who paid around $8,000 to have his name placed on a list of FARC members in order to get judicial benefits as part of the peace deal. When this failed, he became a DEA informant and put the authorities on Santrich’s tail, according to official sources consulted by El Colombiano.

An undercover DEA operation later provided evidence that Santrich was conspiring to sell 10 metric tons of cocaine. However, it is not clear whether the buyers were actual traffickers who had been infiltrated by the DEA, or whether they were all undercover operatives.

(Recordings of Jesús Santrich and his accomplices. Credit: Attorney General’s Office)

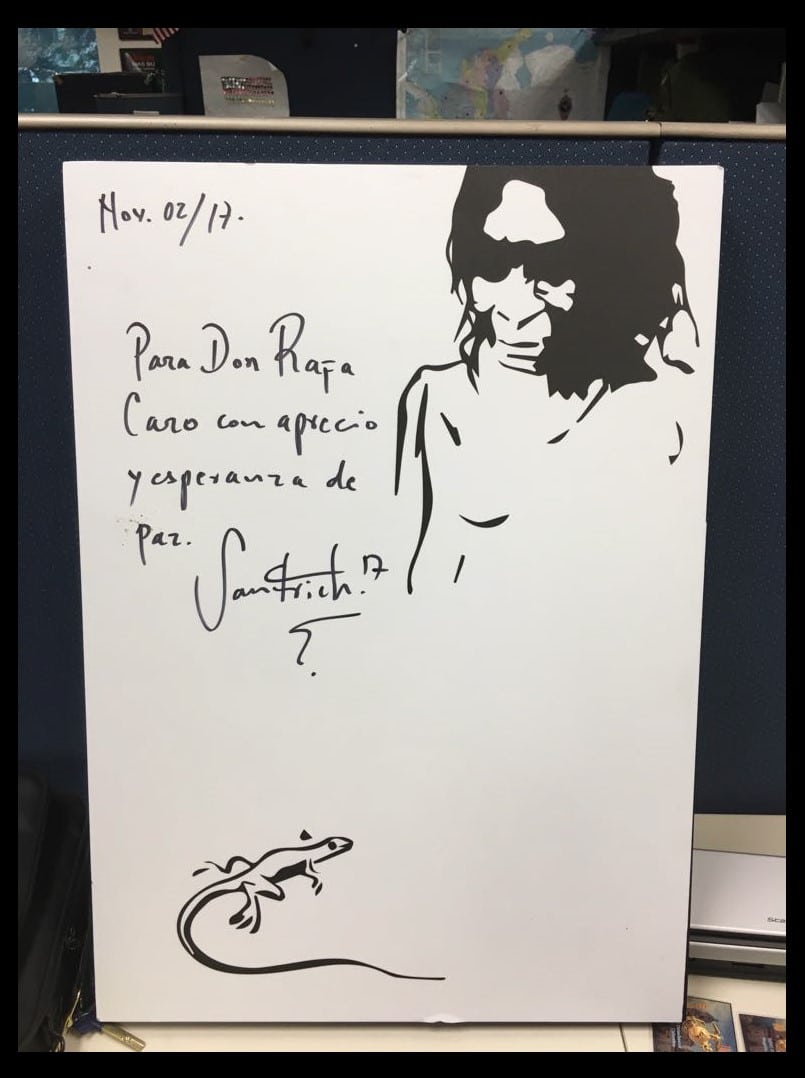

Among the most surprising pieces of evidence presented is a painting, apparently signed by Santrich and dated November 2, 2017. It is dedicated to Rafael Caro Quintero, known as the “Narco of Narcos,” one of the most notorious Mexican traffickers in history. The painting was reportedly a token of trust from Santrich to his “buyers,” but whether Santrich had actual ties to the fugitive crime boss is less clear.

(Painting apparently signed by Santrich as a gift to Rafael Caro Quintero. Credit: Attorney General’s Office)

In contrast to the DEA, Colombian authorities reached Santrich by tracking the nephew of FARC leader Luciano Marín Arango, alias “Iván Márquez.” Marlon Marín had hatched a plan to steal peace funds by embezzling money from healthcare contracts for demobilized guerrillas. The Attorney General’s Office started tracking him, and when the healthcare scheme crumbled, Marin turned to the drug trade, eventually leading investigators to Santrich.

When both countries realized they were following the same suspect, they unified their efforts.

There are also varying reports on Santrich’s partners in Colombia. According to El Colombiano, Santrich was getting his cocaine from the south of the country, where the most powerful FARC dissident networks hold sway. Their main leader is Miguel Botache Santillana, alias “Gentil Duarte,” who — like Santrich — was part of the FARC’s General Staff until he dissented around 2016.

SEE ALSO: Gentil Duarte Profile

Other reports suggest Santrich sourced his cocaine from the Urabeños, the National Liberation Army (Ejército Nacional de Liberación – ELN) rebels and a FARC dissidence lead by alias “Guacho.”

In either case, ties between the former rebel commander and dissidents of the “ex-FARC mafia” would not be too surprising, given their historical relationship.

2. FARC lose congress seat, go on the defensive

Santrich had been selected to occupy one of the 10 unelected congressional seats granted to the FARC’s party as a provision of the peace deal. However, congressmen arrested or prosecuted for drug trafficking cannot be replaced by another member of their party, according to Colombian law. Therefore, the FARC may have lost one of its seats before even setting foot in the legislative chambers. This is a reminder of the political baggage the party will have to carry given that for decades the FARC funded its activities with drug trafficking funds.

SEE ALSO: Luciano Marin Arango, alias ‘Ivan Marquez’ Profile

The FARC party almost immediately rebuked the authorities for Santrich’s arrest, with Iván Márquez insinuating that the peace deal could fall apart as a result. However, party leader Rodrigo Londoño Echeverri, alias “Timochenko,” whose politics differ somewhat from Márquez’s, was more nuanced. After meeting with President Juan Manuel Santos on the issue, Timochenko reaffirmed his party’s support for the peace deal regardless of the actions of any party member.

Protesters have been rallying in defense of Santrich, who is apparently on hunger strike.

3. Judicial vacuums for peace courts?

This will be its first big test for the transitional justice mechanism, the Special Peace Jurisdiction (Jurisdicción Especial para la Paz – JEP), created by the peace agreement to process cases against demobilized guerrillas, including Santrich. However, there has already been controversy regarding the JEP’s role in this arrest.

All crimes committed after the peace deal was signed in late 2016 (which would include Santrich’s scheme) are excluded from the JEP, but only after the JEP rules that they were committed after the cutoff date.

The JEP’s own magistrates are split: some believe the JEP should have been consulted before Attorney General’s Office carried out the arrest order. Others say that there was no misfeasance. Indeed, the laws created for the JEP are not clear on what to do in the case of international arrest orders. These kinds of ambiguities will likely cause delays as the JEP begins to operate fully.

4. Imminent presidential elections

Colombia is little over a month away from potentially game-changing presidential elections. Proof of Santrich’s guilt would give a boost to the political opposition, led by Iván Duque, which has worked fiercely to discredit the peace process and the former guerrillas.

The election of a candidate opposed to the peace deal could stem much government support for the implementation of the accords, which are costly and hard to swallow for many politicians. Furthermore, demobilized guerrillas will be far more likely to split from the process, perhaps to join the FARC dissident groups growing around the country.