Fugitive drug lord Joaquin Guzman Loera, alias “El Chapo,” is living in the Mexican state of Durango, a U.S. anti-drug official told the press, in what could be a calculated move to increase the pressure on Mexico’s government to apprehend the Sinaloa Cartel leader.

A unidentified official from the U.S. government’s Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) told newswire EFE that Guzman is living in “rough terrain” in the mountains of the west Mexican state. The kingpin escaped prison in a laundry basket more than a decade ago, and since then has managed to evade every attempt to recapture him.

There have been reports for some years that Guzman was living in the Sierra Madre mountains. In 2007 he reportedly took over a village in the area in order to hold his own wedding, and in 2009 the archbishop of Durango said publicly that Guzman lived in the municipality of Guanacevi. “Everybody knows this, except the authorities,” he stated.

What is different about the latest allegations is that this time U.S. government representatives are the ones claiming to know where Guzman is hiding. This could be an attempt to put pressure on the Mexican authorities, embarrassing them into gathering their forces to catch the cartel boss.

The government has often been accused of sheltering the Sinaloa Cartel and choosing instead to concentrate their efforts on pursuing rival criminal groups. While this is not proven, a lack of will on the part of the authorities, and the outright corruption of some sectors of the security forces, are certainly a factor in Guzman remaining at liberty.

The Sinaloa leader’s decade on the run has been made possible by several other factors. A key ingredient is his ability to win grassroots backing from some sections of the population, who collaborate in keeping his hideout secret. Guzman could not remain hidden without the support of a large number of ordinary people who see themselves as owing support to him, not the government, despite the large rewards on his head. The EFE report quotes the same anonymous U.S. agent as saying that Guzman knows all the people around his mountain hideout, and that “if there is any movement of anyone, they know.” This kind of early warning system, allowing him to hear in advance about anything which might herald a security forces raid, is crucial in allowing him to remain at large.

One element in winning this support is Guzman’s careful cultivation of his public image. He presents himself as a Robin Hood-style outlaw figure, working on the side of the common man and against the authorities. This reputation is bolstered by stunts such as his widely-reported trips to restaurants, where he allegedly greets each fellow diner personally, and pays everyone’s bill afterwards.

His long flight from justice is the subject of various “narco corridos,” popular folk-style songs about drug traffickers. One of these, released last year, celebrates his life in hiding, and says he is helped by the army; “I like being on my ranch, the soldiers take care of me, and also of my fields.”

Guzman’s ability to command the respect and even affection of segments of the population is not unique among large-scale criminals in Mexico, where drug syndicates often have, or at least claim to have, strong ties to the regions where they developed. One example of this is the Familia Michoacana, which plays on regionalist sentiment in Michoacan in order to drum up local support.

More prosaically, Guzman’s ability to evade recapture for so long is due in large part to his billion dollar fortune, which allows him to buy off both members of the population and local law-enforcement bodies.

Guzman’s story invites comparison to that of an earlier fugitive drug lord – Colombia’s Pablo Escobar. The Medellin Cartel leader likewise enjoyed a measure of grassroots support in his native part of the country, along with the complicity of some local authorities that were intimidated or bribed into helping him. What ended the game for Escobar, who was shot dead by police in 1993, was the combination of two things: the determination of U.S. authorities to bring him down, and the aid they were given by his enemies, funded by rival organization the Cali Cartel.

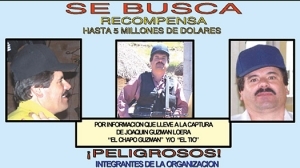

Guzman already has one of these factors securely in place – lots of his rivals want him dead, from the Juarez Cartel to the Zetas. The U.S. has for many years been seeking his extradition, offering a five million dollar reward for his capture, but the DEA’s latest comments could signal a new commitment to push Mexican authorities into finally capturing Guzman.