“The Ghost” had fled Medellín, tied off loose ends in the underworld and perhaps suspended his drug trafficking activities. He disappeared with millions of dollars. That kind of money is hard to hide.

We found out who Memo Fantasma was via a company ID card. The card said his real name was Guillermo León Acevedo Giraldo, of Inversiones ACEM S.A., which engaged in property development. It was a familiar tale: Construction has long been a favorite tool for money laundering. And Memo had made millions of dollars as a top paramilitary drug trafficker. He had to have stashed that money somewhere, so in order to find the Ghost, we decided to try to follow its trail, starting with this card.

There used to be a well-established path for drug traffickers and their money. First, they simply spent it. Soon it began to attract attention. Then, they started to launder it, creating companies through which the money could pass, before being able to spend it again.

*Drug traffickers today have realized that their best protection is not a private army, but rather total anonymity. We call these drug lords “The Invisibles.” This is the first article in a six-part series about one such trafficker, alias “Memo Fantasma,” or “Will the Ghost.” Read all chapters of the investigation here, or download the PDF.

These companies were usually put under the names of family members or close friends or relatives, until there were no more trusted third parties. Then, they got more sophisticated — going international, creating a labyrinth of different companies, which opened and closed, across different financial and legal jurisdictions. The tactics made money well-nigh impossible to track except for those with specialist forensic accounting skills.

The longer drug traffickers are in business, the more money they earn and the more sophisticated their laundering operation becomes. Still, there are always traces, even with the best of them. By 2008, while still only 37, Memo had been in the drug business for almost two decades and had seen hundreds of millions of dollars pass through his hands and those of his paramilitary partners. Surely, he too had left a trace somewhere.

Memo’s Investments in Colombia

The first company we could find for Memo was set up on February 1, 1994. It was just after the death of Pablo Escobar and after Memo had stolen the load of cocaine that kick-started his criminal career. It was in his real name, the one we had found on that company ID, Guillermo León Acevedo Giraldo, and it was registered to an address in Envigado, the home of the Medellín Cartel. Memo was just 22 years old. It remained open until 2004, at which point Memo was moving tons of cocaine as part of the United Self Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia – AUC).

“Zara,” the scorned lover, gave us the name of a man she insisted was Memo’s principal accountant, Gabriel Tapias Restrepo. We found his name linked to several companies in Córdoba, where Memo was known to have properties, most linked to ranching activity and a rice production company. Several sources had spoken of Memo having huge ranching properties around the municipality of Buenavista in Córdoba.

“Once we went to his farm in Buenavista, we came via the airport in Caucasia, because he had a plane,” stated José Germán Sena Pico, alias “Nico,” who had worked with Memo in the Central Bolívar Bloc (Bloque Central Bolívar – BCB), a faction of the AUC umbrella network.

SEE ALSO: Money Laundering Tactics Adapting to Colombia Cocaine Boom

We searched through the partners and workers associated with the company ACEM. Many were members of Memo’s extended family. These included his daughter, mother and grandmother, mother-in-law and several cousins. Putting these names into the company databases in different Chambers of Commerce, we found 12 more companies in Colombia linked to these or other relatives, with assets in the tens of millions of dollars. It seemed we had found a network of relatives in different businesses who could be acting as fronts, or “testaferros.”

Also in Medellín we found Guillermo Acevedo’s name on a company called Palome S.A.S., registered alongside a Leydi Daihana Villa.

Alias “Ernesto,” a rival Medellín drug trafficker who appeared to hate Memo, stated that many of Memo’s properties and companies were in the name of ex-wives and girlfriends, who managed much of his money laundering activities. According to Zara, Memo had at least five children with different partners, two with his current wife. And if we had found more than a dozen companies fronted by relatives which were worth millions of dollars, how many more existed under the names of these former lovers and their children?

It was clear that Memo was not only using land and cattle to launder his money, but seeking to reinvent himself as a rancher and landed gentry, distancing himself from his early life growing up poor in Medellín. This also coincided with his latest choice of partner, his current wife Catalina Mejía, who came from a high-class family in Medellín.

There were some companies that weren’t principally money laundering opportunities, but more linked directly to his business of smuggling drugs. Multiple sources had spoken of Memo’s aviation company based out of Medellín’s domestic airport, Olaya Herrera. Indeed, it was explicitly mentioned during testimony given by Nico to the Colombian Justice and Peace Tribunals, created to oversee the legal side of the paramilitary demobilization.

“The things that he [Memo Fantasma] managed were very big scale. He used to have a hangar in the airport of Olaya Herrera,” testified Nico.

A couple of sources had mentioned the names “Aviel” and “SASA.” Sure enough, we found a company, “Aviones Ejecutivos Ltda Aviel,” had been set up in 1999, just as Memo’s criminal career was beginning to take off, while there was another company, Sociedad Aeronautica De Santander S.A. The name Guillermo Acevedo did not appear on either company papers, but Memo’s criminal ally, Francisco “Pacho” Cifuentes, was listed as one of the partners in Aviel, further strengthening the evidence of a partnership between the two men and the existence of a drug trafficking route leaving the airport in Medellín and bound for Mexico.

Memo’s principal company, ACEM, had been set up in 2007 in Bogotá. This seemed like the best place to start if tracking Memo’s whereabouts. “Olga,” a member of the social circle of Memo’s in-laws whom we have spoken to before, gave us another reason to start looking for The Ghost in the Colombian capital.

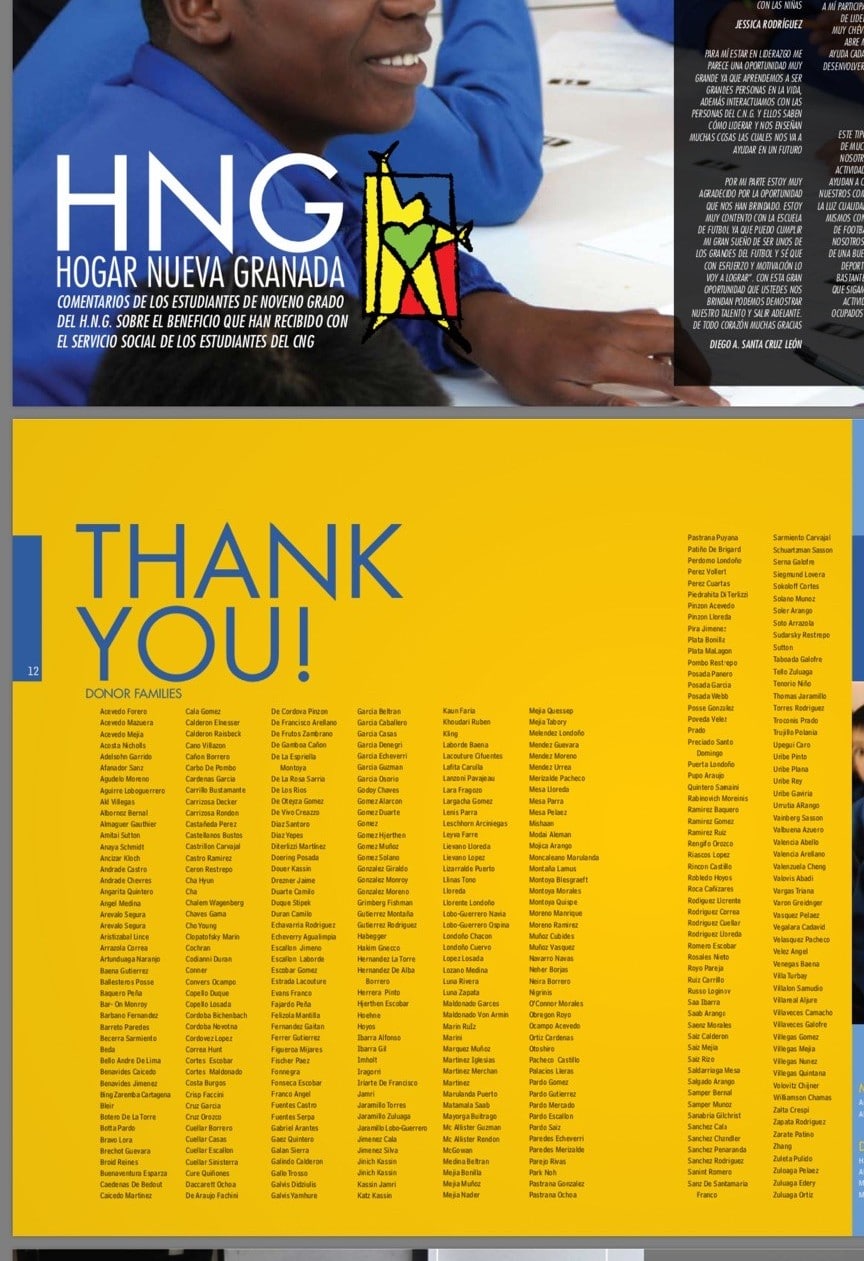

“They moved to Bogotá. We heard that when one of the family members boasted that Memo and Catalina had got their two daughters into the Nueva Granada school, thanks to a recommendation from Marta Lucía Ramírez.”

This was a heart-stopping moment. I asked whether this Marta Lucía Ramírez was the former defense minister, the former presidential candidate for the Conservative Party and the current vice president of Colombia.

“Yep, that’s the one,” said Olga, nodding vigorously.

I now have to engage in full disclosure. I have known Marta Lucía Ramírez for many years, and been invited by her to Club El Nogal, Bogotá’s elite social club, on a couple of occasions. I have always admired the role she played at the top levels of the political world, in a country where there has still not been a female president.

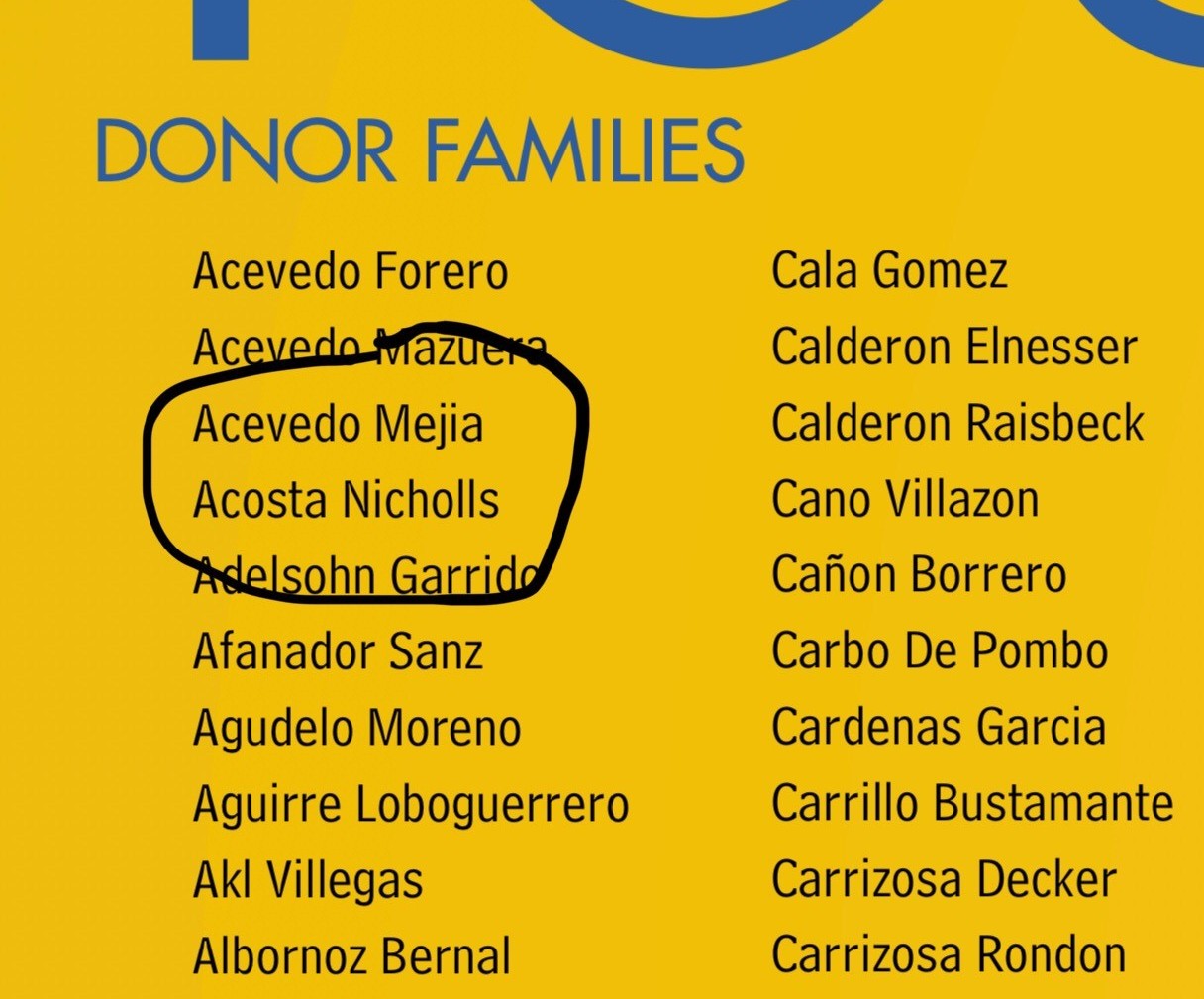

Nueva Granada is one of Bogotá’s most exclusive schools. There is a long line of parents hoping to get their children accepted. That Memo Fantasma, a Medellín drug trafficker, had managed to get his children in did speak to some kind of influence peddling, or “palanca,” as it is called in Colombia. And Marta Lucía Ramírez has that kind of pull. While the school would not give out information on students or their parents, they do publish the list of donors.

One Step Closer to the Ghost

Once in Bogotá, the next step was to visit the office registered for ACEM, at Carrera 14 Nº 85-68. Arriving at the building and mentioning the name Guillermo Acevedo, I was stunned to be let through by security. In the lift up to the fourth floor, in quiet panic, I thought about how I would handle actually meeting Memo Fantasma.

The door was answered by a secretary who introduced herself as Jimena. I pretended I had a meeting with Mr. Acevedo and acted surprised to find he was not in the office, which was very small, with a couple of work stations then a big desk and meeting area at the back.

“Where is Señor Acevedo?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” the secretary replied.

“When are you expecting him back in the office?”

“I don’t know,” said Jimena.

“Can you give me a contact number for him?”

“No, but if you give me a name and number, I can give him your details,” she said.

“I don’t think so.”

Jimena did not blink when I refused to hand over my details, simply nodding. This was clearly no normal office, no normal business, with no normal way of interacting. It seemed that Guillermo Acevedo was almost invisible even to his own secretary, or that she had orders to never give out contact details or whereabouts. This sounded like our Ghost.

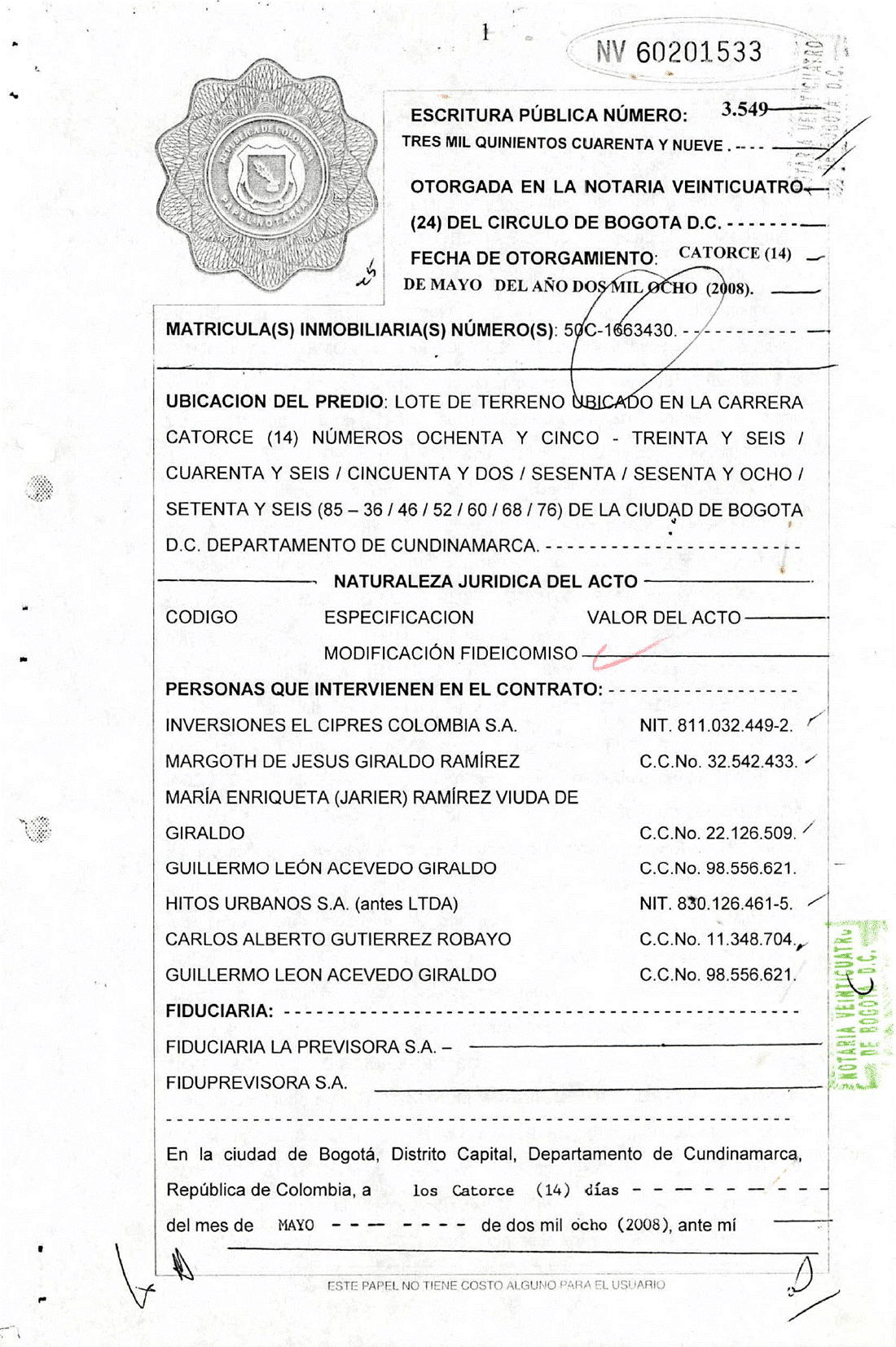

Also registered at this address was another company, Inversiones El Cipre SA. Three of the people listed with ACEM also appeared as being employed by Inversiones El Cipre, although in different roles. Guillermo Acevedo had no direct link to this company, but it was another property development company with ambitious projects around the Colombian capital.

We found Memo’s fingerprints, but no direct links to two massive development projects in Bogotá, one near Parque 93, the city’s most exclusive restaurant district, and another at the corner of Calle 100 with Seventh Avenue, the capital’s main drag. Both of these properties offered the capacity to launder tens of millions of dollars.

Following the names of Memo’s extended family, we came to a series of properties in one of Bogotá’s most expensive neighborhoods. Using his mother’s and grandmother’s names, Margoth de Jesús Giraldo Ramírez and María Enriqueta Ramírez, Memo had acquired a series of lots on one city block, Calle 85 with Carrera 14.

He legally had power of attorney for both women, allowing him to act freely in their names. Today, on this block, stands the luxury development known as Torre 85, offering the swankiest office space in the city. Such a development would have cost tens of millions of dollars to build and made tens of millions more in profit.

How had Memo turned the lots he bought into this enormous building? Some further digging led us to the company that had managed the Torre 85 development and construction: Hitos Urbanos Limitada (company ID or NIT: 83012661-5). The shareholders of Hitos Urbanos were Marta Lucía Ramírez, Colombia’s current vice president, her husband Álvaro Rincón and their daughter.

SEE ALSO: Coverage of Elites and Organized Crime

Rincón still runs Hitos Urbanos and was happy to answer questions. He admitted to working with Guillermo Acevedo in the development of the Torre 85 project.

“I just worked with him on this one project. He came to our office and was presented as a rancher looking to move into the real estate business.” Rincón stated. “He was not a partner, he delivered the properties and in return received some money and some of the offices when the project was completed.”

The properties, a series of small houses, were all acquired by Memo in different names. They were later lumped together as part of the development deal that became Torre 85. We found all the documents pertaining to the agreement, some of which were forwarded by Rincón. There was one which put all of the lots into one fund, a normal step before development begins. In this document, Memo, his mother, his grandmother, the company El Cipres and Hitos Urbanos all appear together.

In return for handing over the properties, Memo ended up with at least five offices in the building, along with 45 parking spaces. The properties were delivered in part to Inversiones El Cipre SA, proving that Memo has links to this company as well, although his name appears nowhere on the official paperwork. These offices with their parking spaces, once completed, were worth tens of millions of dollars. These were “clean” dollars, made with a company linked to one of the most powerful women in Colombia. Again, Memo had showed his intelligence, cleaning his money, entering the real estate and property business allied with Bogotá’s elite, while getting his children into the capital’s most exclusive school. In a matter of a few years, Memo had turned “Sebastian Colmenares,” a paramilitary drug trafficker, into a respected and socially acceptable property developer moving in elite circles.

As well as following the money property trail, we sought to discover Memo’s digital footprint. We asked a friend, with a company that specializes in tracking on-line presence, to look into Guillermo Acevedo and his family. He scoured the Internet for any mentions. He came up with a couple of legal business registrations we had already found, but there was nothing on Memo and his wife Catalina. Absolutely nothing. For one of Memo’s daughters, the search turned up an Instagram page, with the photo only in silhouette, and two other mentions from when she participated in high-level show jumping and had to register under her real name.

“There is no way in today’s world that you have no digital footprint unless you live in a cave somewhere,” our expert said. “For Guillermo Acevedo, there was nothing, not even a picture where he had been tagged by a friend. This is not chance, a professional has wiped their digital footprints and implemented extreme digital security measures.”

But alias “Olga” was not yet done talking about Memo’s movements.

“He is no longer in Bogotá, he now lives in Madrid.”

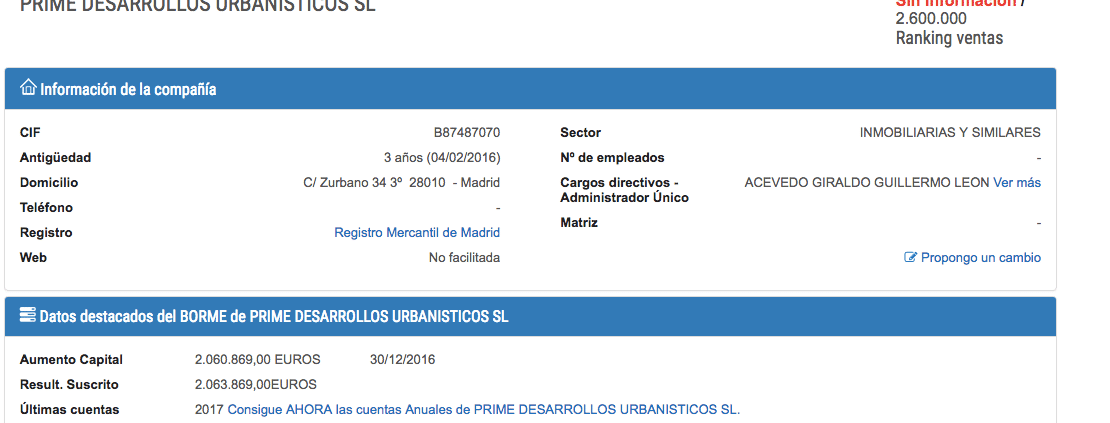

Yet again, Olga’s information was accurate. A search of company databases in Madrid, and speaking to contacts in the Spanish authorities, came back with several results for Guillermo León Acevedo Giraldo. These included two companies, one based in Madrid, Prime Desarrollos Urbanísticos, the other, Promensula Desarrollos SL, operating in Seville. It seems Memo was now in the international property development business and had begun with an investment of more than five million euros.

PRIME DESARROLLOS URBANISTICOS S.L. (España)

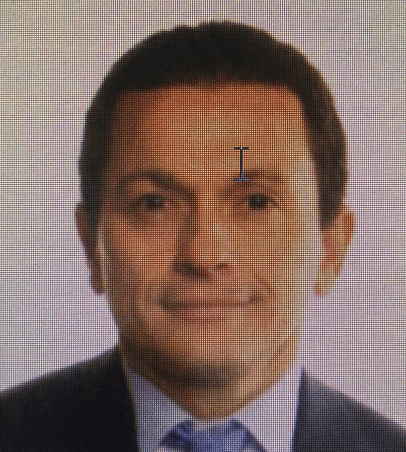

We found a photo from Memo’s Spanish ID card.

He appeared prosperous and happy. It was time to go to Spain and see the Ghost close up.

*Investigation for this article was conducted by Angela Olaya, Ana María Cristancho, Laura Alonso, Javier Villalba, Juan Diego Cárdenas and María Alejandra Navarrete.