On May 27, 1964 up to one thousand Colombian soldiers, backed by fighter planes and helicopters, launched an assault against less than fifty guerrillas in the tiny community of Marquetalia. The aim of the operation was to stamp out once and for all the communist threat in Colombia. The result was the birth of the longest running communist insurgency in Latin America: The FARC.

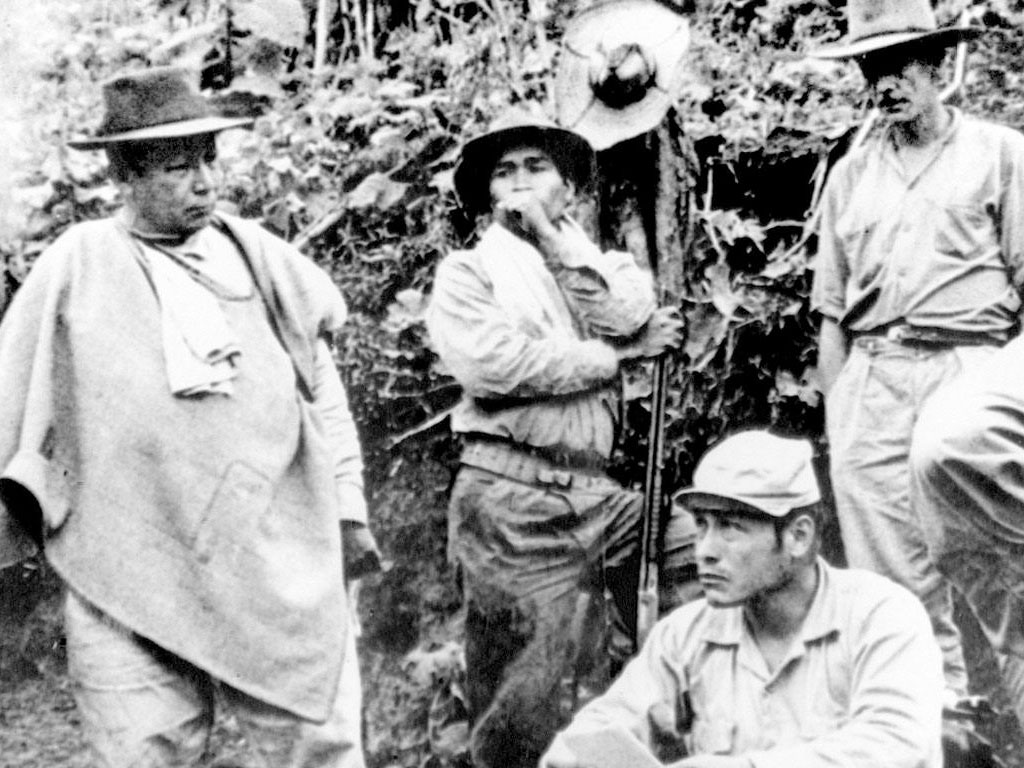

Marquetalia was one of the ostensibly communist “independent republics” that sprung up in Colombia’s isolated and neglected rural areas in the 1950s. It was home to around 50 families of communists, outcast Liberals and other outsiders, and protected by a small band of guerrillas led by a man already building a fearsome reputation; Pedro Antonio Marin, alias “Manuel Marulanda,” or “Tirofijo” — “Sure Shot.”

The operation to take Marquetalia lasted nearly two months. Marulanda and his men were outnumbered and outgunned, but they fought the military back and then slipped away.

This article is the second part of a four-part report that focuses on the history and future of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) as the end of nearly 50 years of conflict with the Colombian state looks possible. Read the other chapters here.

Five months later, the survivors regrouped and staged their First Conference, and the guerrilla insurgency that would become the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) was born.

Before Marquetalia, Marulanda had been a rogue Liberal, a veteran of the civil war between Liberals and Conservatives who had broken ranks rather than turn on the communists that had fought at his side. At the conference, Marulanda declared himself a communist revolutionary, dedicated to the overthrow of the Colombian state.

Marulanda became the driving force and military mastermind of what was then the “Southern Bloc” and in 1966 would become the FARC. At his side was Luis Morantes, alias “Jacobo Arenas,” a trade unionist, Communist Party leader and Marxist theorist, who assumed control of the rebels’ political wing.

Together, these two men — one military commander and the other Marxist ideologue — formed the backbone of the FARC.

The guerrillas, acting as the armed wing of the banned Communist Party, spread through rural Central and South Colombia, but during the early years, their numbers never got far over 500 and plunged as low as 50.

La Revolucion Vive

After surviving their first years of tenuous existence, the FARC began to grow slowly but steadily in the 1970s. As they did, they adopted ever more sophisticated tactics, in both the military and political arenas. They set up a seven person High Command — the Secretariat — in 1974 and divided their army into fronts, with each running its own combat units, intelligence gathering, finances, logistics, public order and mass work programs. They also began infiltrating small towns, courting favor by imposing their own form of law and order (pdf).

Although the FARC were already funding their struggle through kidnapping and extortion, for many Colombians they remained romantic rebels. Their image was polished by the government’s brutal and violent oppression of any left-linked political movement — oppression which pushed new recruits into the arms of Colombia’s insurgent groups.

SEE ALSO: FARC Profile

By 1982, the ragged band that had escaped Marquetalia formed the core of a 3,000 strong guerrilla army, with 32 fronts. At their Seventh Conference, the rebels marked their growing stature with reforms to strategy and structure that would shape the next phase of the Colombian conflict.

Marulanda and Arenas used the conference to present their eight year plan to seize power. The blueprint included a military strategy to slowly surround the cities by advancing throughout the countryside. “The FARC will no longer wait for the enemy to ambush them, but instead will pursue them to locate, attack and eliminate them,” the rebels declared.

The FARC also made military reforms, including the addition of “EP” to their name, for “Ejercito del Pueblo” (People’s Army), new disciplinary codes and recruitment guildlines, which allowed for recruitment of children as young as 15.

However, perhaps the most critical move of the conference was a minor reform to fiscal policy. For the first time, the FARC was to tax coca production, as the rebels’ need to fund their expansion overcame their moral concerns about the “counter-revolutionary” drug trade that had exploded in the country. The resulting boost to income would take the FARC to the next level in the conflict.

While the FARC were planning their path to power, the Colombian people elected a president promising to seek peace, Belisario Betancur, in 1982. The new president reached out to the insurgents, and, for the first time, the FARC participated in high level peace talks.

As part of the process, the FARC launched a political party — the Patriotic Union (UP), in 1985. While the FARC initially dominated the party, it also captured the imagination of a broad range of leftists, peace campaigners, and those disillusioned with a closed shop political elite. In elections the year after the UP was founded it won 14 congressional seats — two of which went to FARC commanders — along with numerous seats in state congresses, and 351 council seats.

However, while the state was talking peace, a counter-insurgency movement was gathering strength in the shadows. Drug traffickers, land owners and the country’s social and economic elites, tired of the guerrillas’ kidnapping and extortion, began to fight back with death squads and private armies.

These burgeoning paramilitary groups, in many cases backed by the Colombian security forces, saw the UP as the FARC’s soft underbelly and easy targets. Before the killing was done, an estimated 3,000 UP militants and leaders had died, among them two presidential candidates, eight congressmen, 13 state deputies, 70 councilors and 11 mayors.

The slaughter drove the FARC back into the mountains, abandoning the UP to its fate as the already rocky peace process stumbled towards its end. The door to politics had clearly been slammed shut, and the military wing took priority.

Throughout the negotiations, the FARC never showed any serious intention of laying down their arms, following instead the strategy of the “combination of all forms of struggle.” Meanwhile, the government failed to deliver on promises of security for the UP and social reforms. These failures were to prove costly.

Hasta la Victoria?

The FARC emerged from the chaos and killing of the 1980s not weakened, but stronger. Their new found wealth from taxing the drug trade, coupled with the pause in hostilities during peace talks, had enabled them to build strength and nearly triple in size.

The rebels were also armed with a new justification for their war. Although the FARC and the UP underwent an acrimonious split, the party’s extermination gave the guerrillas the perfect retort to calls for them to lay down their arms and participate in democratic politics. Armed struggle was the only way.

The 1990s began with a death that would usher in a new era for the FARC. Jacobo Arenas died of natural causes, leaving behind a gaping hole at the rebel’s ideological heart — one that would never truly be filled. His death also removed one of the major obstacles to the FARC increasing its role in the drug trade: his belief that the trade was morally compromising.

The guerrillas established closer relations with drug traffickers to increase their cut of profits, while in some areas they started taking on a more significant role in the trade, processing and smuggling cocaine. They also ramped up kidnapping and extortion to unprecedented levels, making the FARC richer than ever before. The money helped build a force of over 10,000 fighters divided into 60 fronts.

The new FARC military machine went on the offensive. The rebels launched ever bolder and grander attacks, and hit and run guerrilla tactics gave way to a war of movement with strikes against battalion-sized army units and military bases. The rebels increased their territorial control, and began to meddle more in politics, buying influence through threats, violence, corruption, and kidnapping high profile politicians and their families.

The most brazen and daring FARC attack was launched in October 1998, when close to 2,000 guerrillas seized the town of Mitu, the capital of the department of Vaupes. Although the FARC only held the town for three days, the attack sent a powerful statement to newly elected President Andres Pastrana — one he was unable to ignore.

SEE ALSO: Colombia News and Profiles

Just months after the seizure of Mitu, President Pastrana conceded to the FARC’s preconditions to new peace talks — a demilitarized zone covering 42,000 square kilometers that was home to 80,000 people. The region would become the FARC’s de facto mini-state, dubbed “Farclandia.”

The ceding of Farclandia to the rebels was a huge gamble. It did not pay off. The rebels used the territory to hold kidnap victims; plant drug crops; and regroup, retrain and build strength. The government hoped the strains of administering the territory would prove draining, but instead the guerrillas reveled in their autonomy, proudly showing off their “laboratory of peace” to international journalists and civil society.

The FARC also used the peace process to build international support and push for recognition as a legitimate belligerent force in Colombia’s conflict. However, they showed little interest in negotiating. The talks stalled time and again, and eventually broke down amid kidnappings, hijackings, military assaults and claim and counter claim of bad faith and broken promises.

At the start of 2002, President Pastrana declared the talks dead, and military hostilities resumed. The army moved against Farclandia. The FARC murdered the Governor of Antioquia and kidnapped presidential candidate Ingrid Betancourt.

By the time the peace talks collapsed, the FARC had a 15,000 – 20,000 fighter army, which occupied over a third of Colombian territory and was circling the main cities of Bogota, Medellin and Cali. It was well armed, organized, and rich.

The rebels had reached the height of their power during the Pastrana peace talks, but by the time military hostilities resumed, two new, strong enemies were already looming on the horizon: the money, machines and might of the US military; and the cunning, determined and ruthless incoming President Alvaro Uribe.

Another enemy, the paramilitary army of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), was stronger than ever, and on the march. The AUC was more deadly than the Colombian army, and, crucially, fought the guerrillas using their own tactics.