On the morning of Sunday, June 28, 2009, Honduran soldiers burst into the presidential palace in the country’s capital, Tegucigalpa, rustled President Manuel Zelaya from his bed, and took away his cellular phone. As the army disarmed the presidential guard, the soldiers ushered Zelaya into a van and took him to an air force base where he was escorted onto an airplane that immediately left the country. Zelaya said he did not know where he was going until he arrived in San José, Costa Rica.

“I have been kidnapped,” he told a packed press conference later that day from Costa Rica. “Violently, brutally kidnapped.”

What an independent truth commission would later call “a coup,” was the culmination of months of political turmoil in the country. Zelaya claimed he was simply holding a referendum, scheduled for that very June 28, to determine if Honduras should include a so-called “fourth ballot box” in the upcoming November national elections. The fourth ballot box would give voters the opportunity to ask for a constitutional assembly. Zelaya’s rivals — which included his own party in congress as well as three of four other political parties in the legislative branch, the Supreme Court, the military, the Catholic Church and the country’s top business associations — said he had ignored court rulings that made his referendum unconstitutional and was seeking to perpetuate his presidential term like his ally, Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, had already done in Venezuela on numerous occasions. US officials later said they had tried to stave off the removal of Zelaya, but the Honduras military had broken off talks on the day of Zelaya’s ousting.

To be sure, behind “the coup” in Honduras was the specter of Venezuela. During his presidential campaign in 2005, Zelaya had run as an able businessman and moderate reformist for the center-right Liberal Party (Partido Liberal – PL). After facing opposition for many of his proposals from his Liberal Party colleagues and the rival National Party (Partido Nacional – PN), Zelaya had turned to leftist coalitions and unions for support of his agenda. To the consternation of business elites, he raised wages of public and private sector employees, including increasing the minimum wage for all workers by 60 percent. And to the horror of the political elites, he joined Petrocaribe and the Bolivarian Alternative for the Americas (Alternativa Bolivariana para las Americas – ALBA), Chavez’s regional economic and political alliance, which acted as a counterweight to the US-led trade agreements in the region.

The irony, of course, is that ALBA would have little impact on Honduras compared to the coup that ousted its one-time executive promotor. In fact, the chaos that followed Zelaya’s removal from office opened the door to a period of unprecedented criminal activity in the country, which deeply altered Honduras’ political, economic and social landscape. Like ALBA, it emanated from Venezuela and included Venezuelan official participation. Unlike ALBA, it involved some of the same political interests in Honduras that had sought to undermine Zelaya.

Chaos and Criminal Opportunity

Following the coup against Zelaya, Congress installed the head of the legislative body, Roberto Micheletti of the PL, as interim president. The international community, including the US government, rejected Micheletti’s claim to power. Honduras was suspended from the Organization of American States, numerous countries withdrew their ambassadors, and no country recognized Micheletti’s administration.

Political isolation grew as Micheletti declared numerous curfews, shut down opposition media, and dispatched army soldiers and police to quell the protests that had erupted following Zelaya’s removal. These protests only intensified in September 2009, when Zelaya snuck back into the country via a mountain pass and installed himself in the Brazilian embassy in Tegucigalpa, which tried to negotiate a deal that would allow him to retake the presidency until the end of his term. Micheletti responded by declaring a 45-day state of siege, which, among other things, suspended various constitutionally guaranteed liberties.

With each side entrenched, a stalemate emerged, even as presidential campaigning for the November election had begun. National Party candidate Porfirio Lobo won the vote, which saw 50 percent abstention. For some, it was an affirmation that Hondurans rejected Zelaya’s and his allies’ efforts to boycott the process and have him reinstated. But for others, it was deja vu — an affirmation that the country’s political and economic elites had turned the clock back to the 1980s with the help of the military by deposing a left-leaning president.

The US government only reinforced this belief when it recognized the Lobo administration. But the surreal political crisis had hamstrung US cooperation with Honduras, particularly in counternarcotic matters. In the days that followed Zelaya’s ousting, the US government withdrew $33 million in economic and military aid, and it stopped working with the Honduran military and counter-drug forces. At the same time, the Honduran military and police concentrated their forces in Tegucigalpa to deal with the political turmoil. The result was an opening for criminal organizations.

One such organization that took advantage was a Colombian-Venezuelan network that operated along the country’s shared borders. It was run by Jose Evaristo Linares Castillo, a long-time associate of Daniel “El Loco” Barrera, who, along with their other associate, Pedro Oliveiro Guerrero, alias “Cuchillo,” used their criminal networks in Colombia to facilitate the movement of cocaine through Venezuela. While Barrera and Guerrero were associated with right-wing paramilitary groups, Linares was alleged to work with the leftist Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC).

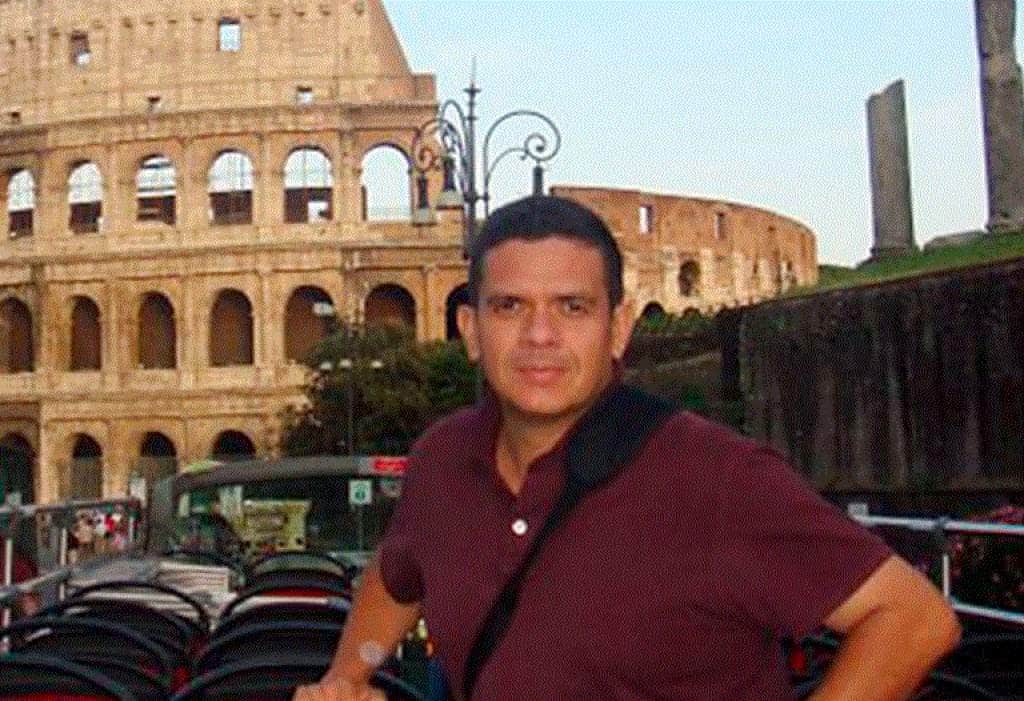

The Linares network included a Colombian-born middle-aged former butcher named Gersain Viafara Mina. Viafara Mina was originally from Cali, Colombia but had resettled in the border state of Apure, Venezuela. And by the time Zelaya was removed from power, Viafara Mina was managing cocaine loads moving from Venezuela through Honduras for Linares and others. In court papers filed by the US government charging Viafara Mina with drug trafficking, an affidavit by a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agent says Viafara Mina coordinated numerous flights between the two countries.

“Viafara-Mina made arrangements to ship the cocaine from Apure, Venezuela to Central America through sources that supplied cocaine, aircraft, and clandestine airstrips to facilitate the cocaine smuggling operations,” the affidavit, written by agent Kimojah Brooks, reads.

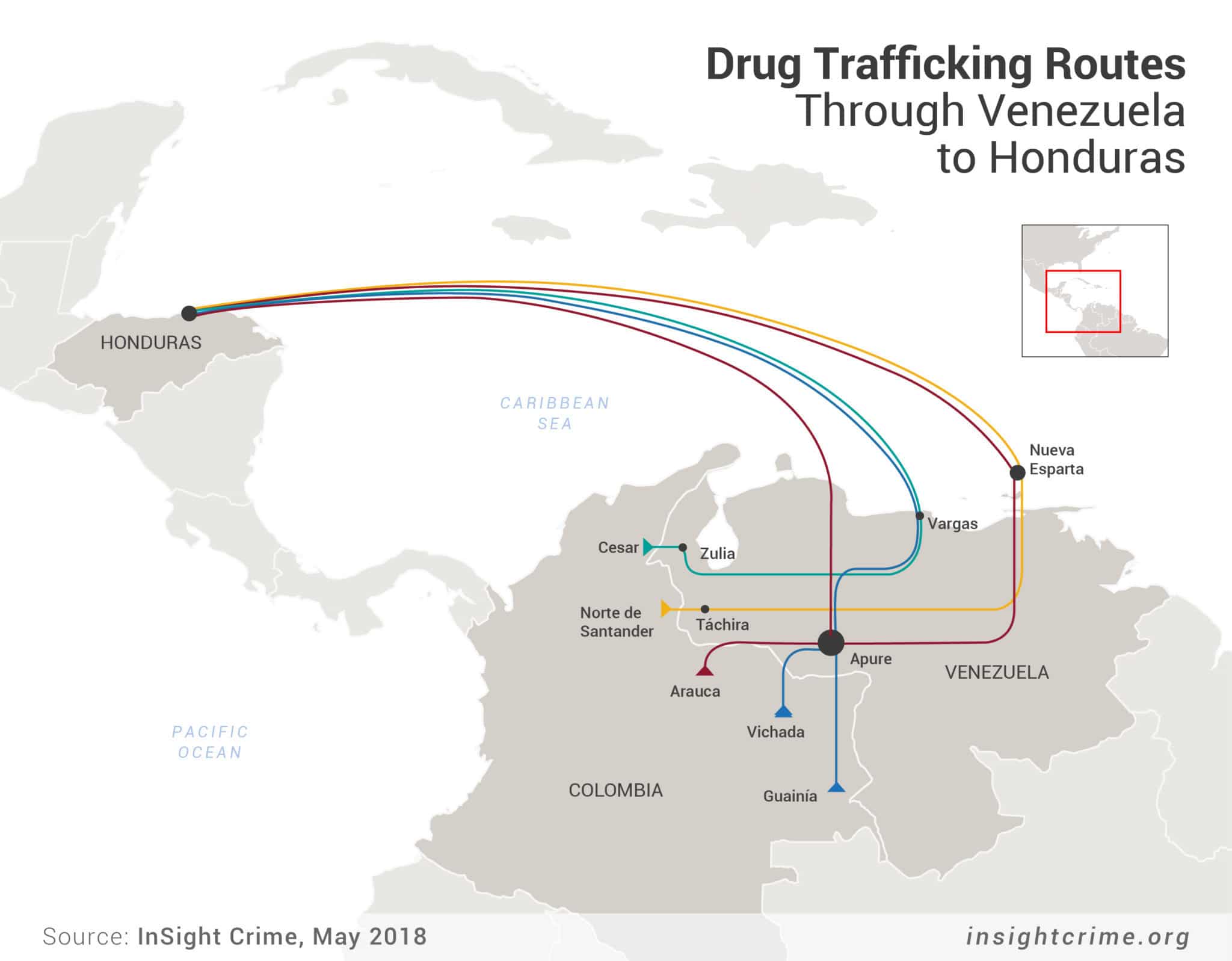

These flights would leave Apure, fly due north towards the Dominican Republic, then take a sharp left along the 15th parallel, which entered Central America along the Honduran-Nicaraguan border. The route allowed these single and twin-engine aircraft to avoid Colombia-based radar detection. The flights were coming in waves, according to a foreign counternarcotic official who was working in Central America at the time and who spoke to InSight Crime on condition of anonymity because some of these cases are still making their way through the US justice system. Each single engine carried, on average, 500 kilograms; each twin engine would take between 800 kilograms and a ton, the counternarcotic official said.

“Air tracks continued to proliferate in 2010,” the State Department’s annual assessment of drug trafficking in the region stated in 2011. “The Joint Interagency Task Force South (JIATF-S) recorded 75 suspect air flights into Honduras during the year, compared with 54 in 2009 and 31 in 2008.”

The report said the majority were from Venezuela.19 The foreign counternarcotic official was more specific. “If there were 100 [air tracks],” the official said, “probably 95 were coming Venezuela.”

The departure point also permitted Viafara Mina and his team to liaison with its support network, which, according to the affidavit, included the FARC and possibly portions of the Venezuelan military. The affidavit is specific on this first point but vague on the second. It says the FARC “provided security at the airstrip” in Apure. But it only makes one specific mention of the Venezuelan authorities, citing an intercepted phone call in which Viafara Mina and a confidential informant identified only as “CC-1” discuss getting an aircraft that had crashed in Apure in May 2011, “from Venezuelan military custody.”

Other parts of the affidavit, however, are less specific. In one section, the DEA agent discusses meetings between Viafara Mina and “members of the military of a nearby country.” These military personnel, the affidavit says, “had access to transponder codes that could be used by pilots to fly in that country’s airspace and access clandestine airstrips there used in connection with the transportation of large quantities of cocaine.” The limited geographic scope of Viafara Mina’s team made Venezuela the logical identity of this “nearby country,” but efforts to confirm this with the US Justice Department went unanswered.

Viafara Mina was captured in 2015, when he crossed into Colombia to purchase a light for his car. He was extradited that same year to the United States, leading to more ripple effects in relations between Venezuela and its neighbors. The extradition reportedly caused a commotion on the Venezuela–Colombia border, where Venezuelan authorities temporarily closed passage to Colombia in supposed retaliation for the extradition of Viafara Mina and another suspected Colombian trafficker, whom El Tiempo identified as “a key witness against uniformed [Venezuelan] personnel connected to illegal interests.”

The Impact on Honduras

It was also 2015, the same year Viafara Mina was arrested, when one of the Honduran networks linked to the cocaine air bridge unraveled, taking with it the vast political and economic network it had created. Sometime in January 2015, Javier and Devis Rivera Maradiaga, the two brothers who had created a criminal group popularly known as the Cachiros, went to a Caribbean island and turned themselves into US authorities. They were charged with drug trafficking and quickly began cooperating with US authorities to lower their sentences and get some members of their family out of Honduras.

The Cachiros had emerged as cattle rustlers in the eastern state of Colón in 1970s. Early on, they had established ties with elite families, such as the Rosenthal clan, to whom they could sell their livestock. The Rosenthal family had started with insurance companies in the 1930s, but later expanded into meat-packing, real estate, agriculture, cattle, dairy products, tourism, banking, television, telecommunications and other businesses. By the 1970s, they were one of the wealthiest families in Honduras. By the late 1980s, Jaime Rosenthal Oliva, the family patriarch, was a prominent member of the Liberal Party and the country’s vice president. By the 1990s, the family was one of the richest and most powerful in all of Central America.

SEE ALSO: Cachiros Profile

Over that same time period, the Cachiros’ criminal portfolio grew to include drug trafficking. The Cachiros were particularly adept at establishing networks that could receive and move cocaine from the coasts and clandestine airstrips of eastern Honduras to Guatemala. In 2004, following a tiff with their chief rival, the Cachiros went on a three-country search-and-destroy mission before catching up to him in a Honduras prison where they had him killed.

By 2009, the year Zelaya was unceremoniously removed from power, the Cachiros were one of the largest illicit transport groups in the country. They had teams of collaborators throughout the area that arranged for the aircraft landings, set up the lights along the clandestine airstrips, offloaded the illicit merchandise and moved it to a safe location. They also established local connections — including with the police, local politicians and judicial authorities — to ensure the drugs would not be confiscated, or if they were, that they could be recovered at a minimal cost.

The price the Cachiros charged for this service was roughly $2,000 per kilogram of cocaine, the difference in cost of cocaine between Nicaragua and Guatemala. The sums of money generated by this business were immense, especially for a place like Honduras. Honduran authorities estimated that by the time they began confiscating the Cachiros’ properties in 2013, the group had accumulated up to $800 million in assets, or about half the total amount of the country’s top export, coffee, during any given year.

As the Cachiros’ illicit businesses grew, so did their connections and their ability to penetrate the highest levels of political life. By the early 2000s, the Cachiros had forged ties with the Rosenthals and other elites in banking, hotels, agribusiness and via a soccer team they helped finance. They used their legitimate businesses to get state contracts to build and maintain roads, as well as work on other infrastructure projects. And they became business partners with the then-first family and possibly the future first family.

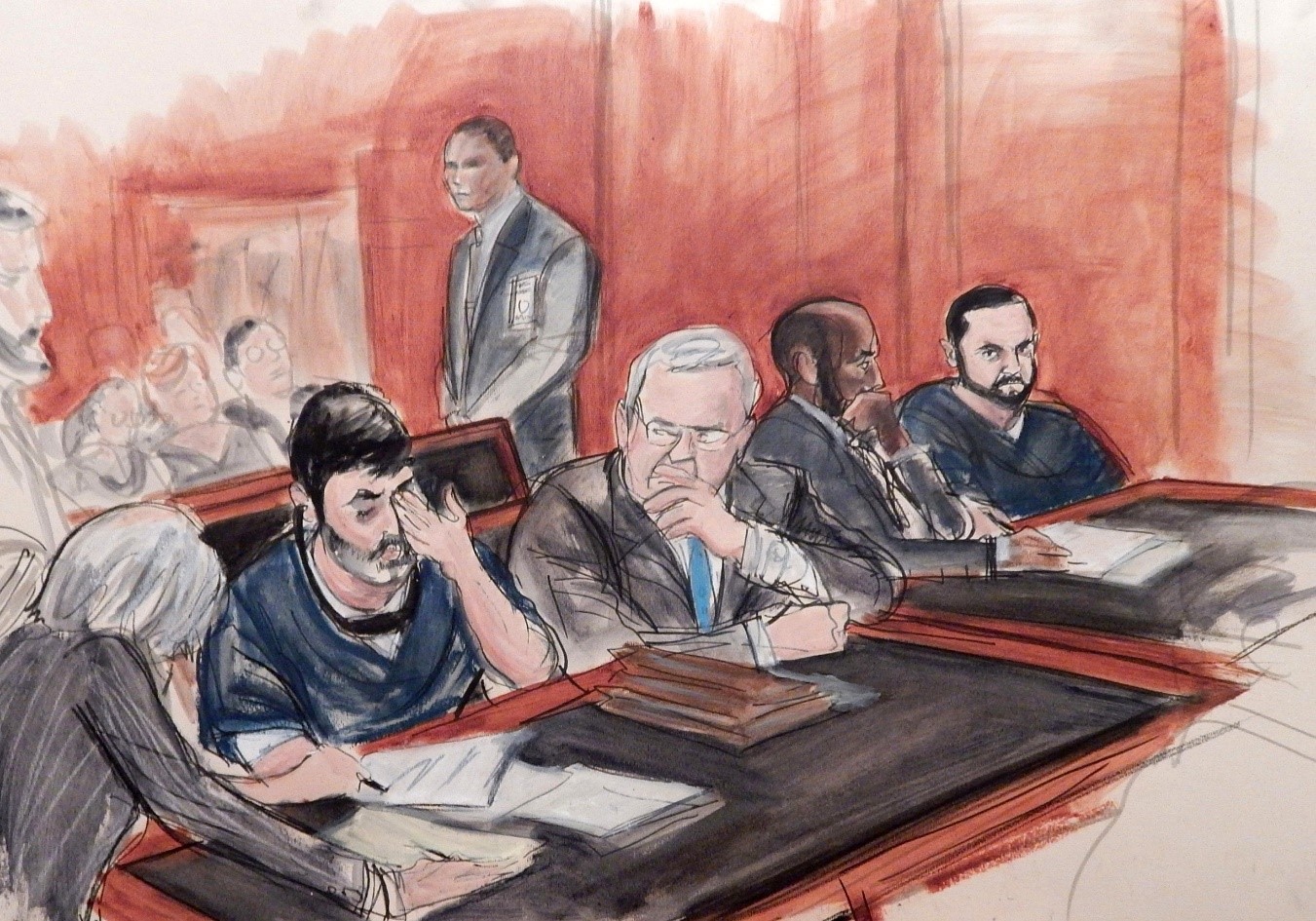

After the Rivera Maradiaga brothers handed themselves to US authorities, the consequences for these elites who had worked with the Cachiros came swiftly. In May 2015, in a sting coordinated with Haitian authorities, US authorities arrested Fabio Lobo, the son of former President Porfirio Lobo, the same man who had won the controversial November 2009 election following the ousting of Zelaya. In October 2015, the US Justice Department indicted three members of the Rosenthal family and a lawyer for their business conglomerate on charges of money laundering related to corruption and drug trafficking networks.

Lobo’s case was particularly damaging for his family. He was taken to the United States, where he pled guilty. At his sentencing hearing, Devis Rivera Maradiaga, the younger of the two Cachiros who had turned himself over to authorities in the Caribbean, testified in a New York City courtroom that Lobo’s father had received bribes in the hundreds of thousands of dollars from the group in return for a promise that the government would not extradite them to the United States, and that Fabio Lobo had worked closely with him to secure and transport at least two loads of cocaine from the Colón area to the Guatemalan border. In his testimony, Rivera Maradiaga also implicated the brother of current President Juan Orlando Hernández to secure money owed to one of his companies.

The Rivera Maradiga brothers were also linked to Venezuela’s “narco nephews” case. Supposedly the Cachiros were also connected to Efraín Antonio Campo Flores y Franqui Francisco Flores de Freitas, the nephews of Venezuela’s first lady, Cilia Flores.

Although these links have not been proven, there was confirmation that a route via Honduras was envisaged, and that the relatives of the Venezuelan president did have links to Central American criminal groups. For more details on this case, see the chapter on the ‘Cartel of the Suns.’

SEE ALSO: Cartel of the Suns Profile

What is clear is that the ouster of Zelaya led to the creation of one of the main cocaine routes from South America to the United States. This route depended on sophisticated drug trafficking structures in Venezuela, and a path of minimal resistance through Honduras.