Juan Carlos Monzón was in South Korea when his boss, Guatemala’s Vice President Roxana Baldetti, received the call that would change their two trajectories – intimately intertwined for the previous four years – forever.

On the other side of the phone was President Otto Pérez Molina. The president had information that an arrest warrant had been issued for Monzón, the vice president’s private secretary and that he was to be arrested when he landed in Guatemala.

This is the second article of a three-part investigation, “Illicit Campaign Financing in Guatemala”, that looks at how the last three winners of the presidency in Guatemala financed their campaigns using hidden funds from drug traffickers to big businessmen. Download the full report here, or read the other articles of this investigation here.

It was April 16, 2015. Baldetti had gone to South Korea to receive an honorary doctorate in social work from the Catholic University of Daegu. In addition to Monzón, Baldetti had her personal assistant and the former Patriotic Party (PP) Congresswoman Daniela Beltranena with her.

According to Beltranena, the vice president team’s initial reaction was one of resignation. Years later, in court, Beltranena would say that she found Monzón and Baldetti crying in the vice-president’s hotel room. The team, she said, was ready to go home.

But Monzón’s decision to surrender would have had widespread implications. The Guatemalan Attorney General’s Office and the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (Comisión Internacional Contra la Impunidad en Guatemala – CICIG) was accusing him of heading a corruption scheme at Guatemala’s customs agency, which would eventually take on the moniker “La Línea” or “The Line,” a widespread scandal that would implicate dozens of officials. But La Línea was a top-down scheme, directed from the presidency by Pérez Molina and Baldetti. And Baldetti was not about to surrender.

Monzón says the vice president ordered Beltranena to make preparations for Monzón’s escape, which included securing assistance from the Guatemalan ambassador in South Korea to get Monzón out of the country.

Baldetti also gave Monzón a new cell phone with international coverage. She had gotten it from the Secretary of Administrative and Security of the Presidency of the Republic (SAAS), the Guatemalan version of the Secret Service, prosecutors told InSight Crime.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, in an exclusive office in Guatemala City, another powerful member of the PP faced a similar dilemma. Alejandro Sinibaldi, the former minister of the powerful Infrastructure, Housing and Communications Ministry, was preparing for a run at the presidency.

However, Sinibaldi had corruption issues of his own, especially related to illicit campaign donations and kickback schemes. He knew that it would not be long before the prosecutors knocked on his door.

The party had financed its rise to power through a series of shell companies that took dark money from a wide range of donors, laundered it and then injected it into the electoral campaign without reporting it to the country’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal (Tribunal Supremo Electoral – TSE).

Guatemalan prosecutors told InSight Crime that as much as 95 percent of the money that the campaign received was not reported. Instead, it went through private accounts.

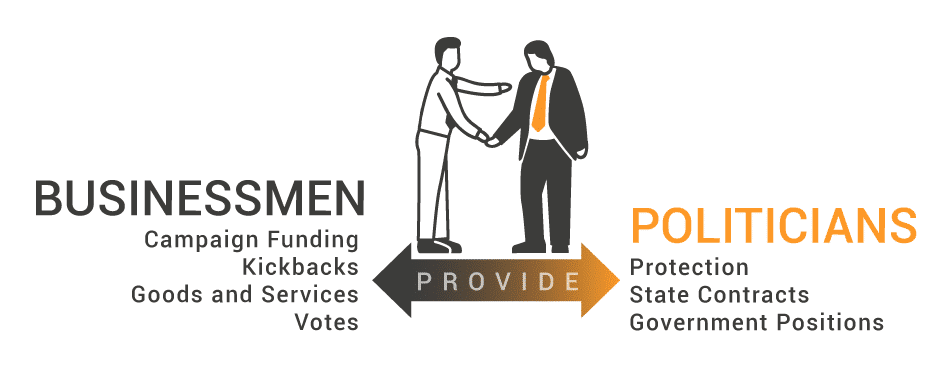

The Pérez Molina and Baldetti government clearly understood that in order to be in politics and make money in Guatemala, corrupt politicians and businessmen use what they call “quotas of power,” or favors, which open doors to contracts and government benefits.

La Línea was just the beginning. Prosecutors would later reveal a series of cases that laid bare the modus operandi of the administration and its allies, and how the PP, perhaps more than any other government before it, had figured out ways to make money from its time in power.

The PP’s arrival to the presidency was a perfect example of “pay-for-play” in Guatemalan politics, wherein companies finance elections to receive benefits or contracts from the government.

And for that, you need operators like Monzón and Sinibaldi, who, realizing that the complex scheme that they were part of was crumbling, faced a decision: flee or surrender to justice.

Campaigns and Companies

Prosecutors say Monzón never imagined that he would become the vice president’s private secretary. Culture and Sports minister would surely have seemed a safer bet. He was already a businessman in the sports industry with military training when he began his dance with the PP, just before the 2011 elections.

Monzón’s company, Canchas Deportivas of Guatemala, had built sports facilities and helped market them for years. And records show that the company had already been awarded close to $2.5 million in government contracts between 2006 and 2011.

Listen to the Podcast: The ‘Car Thief’

Prosecutors say that his initial contact with the PP was through Congressmen Amílcar Aleksander Castillo and Edgar Cristiani, who he knew because of their shared passion for motocross. (During the administration, Monzón would collect at least ten motorcycles, including three high-end motorcycles worth more than $80,000.)

It could have been his taste for adrenaline that led him to commit some of his first crimes. Prosecutors told InSight Crime that when he was young and in the army in the 1990s, the future private secretary of Roxana Baldetti was nicknamed “Robacarros Monzón,” or “Car-thief Monzón.”

In 2001, authorities arrested him and a few other members of a group that stole cars, after their botched attempt to steal one in Guatemala City led to a gunfight with police. He was released, and the charges were dropped.

Ten years later, Monzón began working with the PP, organizing events to attract votes. Quickly, his diligence won him the affection of Baldetti, who entrusted him with managing the campaign in two of the most important electoral districts of the country: Guatemala City and the northeastern department of Petén. Soon after he proved himself worthy again, he was named campaign secretary.

It was around then that Baldetti and Monzón set up one of their first “quotas.” The partner in this deal was Miguel Ángel Martínez, the head of the private security company Grupo Escorpión, which the party hired for the campaign. The vice president promised more of the same once in power. The relationship would, as was made clear to him, be mutually beneficial.

Monzón, meanwhile, began knocking on doors, shaking hands and collecting money. Under Baldetti’s orders, he also started to create the financial infrastructure so that the party could launder the money it got from donors. This included creating shell companies that would collect money from contributors who wanted to remain anonymous. Monzón and Víctor Hugo Hernández, the figurehead of the structure, began to rent apartments and offices that were converted into cash warehouses. They also established a way to deposit checks into the financial system without raising suspicion.

Businessmen and other donors who wanted to win the party’s favor contributed money, as well as goods and services, such as arranging their travel and accommodations, and providing unlimited cell phone usage plans and high-end vehicles. The payments were made via cash, checks and bank transfers. In both cases, the PP gave “donors” the option to receive invoices for services that were never actually rendered.

The cash was moved in briefcases and stored in the campaign headquarters and in several of the apartments and offices rented by Monzón and Hernández. The shell companies created under their names also played a fundamental role in the illicit financing scheme.

“In the reports submitted to the TSE, we see month after month how Monzón and Hernández appear repeatedly as donors when in reality they received funds from other entities,” the CICIG would later point out in its report on what became known as the Cooptación del Estado, or State Co-optation, case.

The campaign contributions came from various sources. Two of the companies were the TV channels Radiotelevisión Guatemala S.A. and Televisiete S.A., which were owned by the same person. According to the Attorney General’s Office and CICIG, these media companies gave contributions to the campaign through at least four companies linked to Baldetti in monthly payments amounting to nearly $2.5 million.

Not all money was spent on the elections. Monzón would later testify that part of the money was kept in the campaign headquarters in “the bathroom area of the vice president’s office.” Money was also hidden in various other offices — inside desks, filing cabinets and safes.

A Photo is Worth More Than 1,000 Lawyers

In 2011, telecommunications giant Claro had a legal problem that threatened to bankrupt its Guatemalan operations. The Telecommunications Superintendency (Superintendencia de Telecomunicaciones) and the Infrastructure, Housing and Communications Ministry (Ministerio de Infraestructura, Vivienda y Comunicaciones) had “resolved” a dispute in favor of its rivals, Tigo, that the two companies had had since 1998. Tigo claimed that Claro had violated the country’s telephone contract laws. The result of the decision, which came in 2011, meant Claro had to pay $400 million to Tigo.

According to prosecutors, Claro had approached then-President Álvaro Colom, but could not get his ear. To make matters worse, Claro’s rival was already well positioned within the PP, which had the clearest path to the presidency. In other words, Claro needed to make a move or possibly lose its business in Guatemala.

To this end, Claro’s general manager in Central America, Julio Carlos Porras Zadik, arranged to meet with José Julio Ligorría, one of the PP’s top operatives. Ligorría was a political consultant, mostly on matters of image and public relations, and he had already positioned himself to be Guatemala’s ambassador to the United States should the PP win the elections.

Ligorría also had strong relations with the army, which brought him closer to the PP’s political circles. His long-time business partner, retired Lt. Colonel Mauricio López Bonilla, became the head of the PP’s campaign and would later be named interior minister, where he would set up his own corruption schemes.

In dealing with Claro, however, the two operatives needed a third, someone with more pull than them, so they turned to Congressman Alejandro Sinibaldi.

Sinibaldi was a social climber. He had grown up comfortably, but far from the luxuries and excesses of the country’s super elite with whom he now hobnobbed. His personal rise to power began when he married María José Saravia, the daughter of a well-known Guatemalan lawyer and businessman. Saravia’s family owns Central American Brewery, one of the largest beer makers in the country and the region.

But prosecutors told InSight Crime that Sinibaldi never quite fit in nor was he accepted by his wife’s family, and he sought to make his name in politics. Using his connections, he was appointed tourism minister in 2004, a platform that he used to reach Congress with the PP in the 2007 elections.

By 2011, he was doing business with some of the richest and most important men in the country, and he did not miss a single moment to show off the social, political and economic capital that he was amassing.

So it was with Claro. According to Porras Zadik, Sinibaldi told Ligorría that for the PP to deal with Claro’s legal problems, Claro needed to donate to the campaign an equal or greater amount than Tigo had.

To channel the funds, Claro contracted the services of Sinibaldi’s public relations companies, including Impresos Urbanos and Imágenes Urbanas. The companies invoiced Claro billboard ads and the creation of graphics and communication strategies. The services were never provided.

After Claro’s two million dollar payout to the PP via Sinibaldi’s companies, the PP congressman set up a meeting in Mexico in August 2011 between the then-candidates Pérez Molina and Baldetti and Carlos Slim, the majority shareholder of the company that owns Claro.

The three took a photo that was published in several Guatemalan media outlets. The PP’s strategy, CICIG Commissioner Iván Velásquez would explain later, was to “scare” Tigo.

One month after the infamous meeting organized by Sinibaldi, Claro and Tigo reached an agreement.

The PP Co-opts the State

Once in office, Molina and Baldetti immediately rolled out the corruption scheme they had developed during the elections. For the presidential inauguration, the government paid almost $4,000 to HJ & AV, a company owned by Víctor Hernández – the figurehead who had worked with Monzón to launder campaign proceeds – to provide decorations for the inaugural ball. Hernández was later given a salaried government job, for which he did absolutely nothing.

Indeed, from the day it took power, the PP government began signing contracts with companies in exchange for bribes, interfering in court cases to favor its donors and placing its allies in key positions to skim from the state.

Monzón was at the center of many of these schemes. Prosecutors estimate that he alone managed to move at least $21 million in bribes and that the criminal structure as a whole received at $67 million through more than 450 government contracts.

As part of his job as the vice president’s private secretary, Monzón collected monthly bribes of $20,000 as kickbacks for state security contracts that were awarded to at least three companies related to Martínez, the legal representative of Escorpión, the company that had provided security during the campaign. Martínez was also appointed the undersecretary of SAAS, the secret service group that later gave Baldetti the cell phone she would pass to Monzón to use during his escape from justice.

In all, Grupo Escorpión got more than $8 million in contracts during the first few years of the PP government. But in Guatemala, these contracts have a price. Prosecutors say the company spent more than $700,000 in bribes in exchange for the contracts, part of which was hidden in invoices for private security guards that never provided the services.

Monzón also cashed in. After the PP took power, his sports company was transferred to his wife’s name. And between 2012 and 2015, the company received at least 13 government contracts.

Monzón also set up a series of agricultural projects for the companies Tigsa and Mayafert. In return, the two companies paid more than $660,000 in bribes to him and his boss, Vice President Baldetti.

Prosecutors say that Pérez Molina and Baldetti took 60 percent of the money paid in bribes. The rest was distributed among the other participants. The key modus operandi remained the same both during and after the elections: altering documents and falsifying invoices. This was particularly evident in the case of La Línea, a scheme that falsified documents to lower import duties for companies bringing goods through Guatemala’s Quetzal Port in return for bribes to the PP officials and their operatives.

Although initially, the prosecutors said that Monzón was at the top of the structure, a judge in the case later downgraded him to “operational leader.” Specifically, the judge said that Baldetti appointed him to coordinate and supervise the part of the scheme managed by Guatemala’s tax administration known by the acronym SAT.

In practice, this meant that he was in direct contact with a top SAT official, making sure that taxes were in line with the declarations in port records, that mid-level officials were complying with the legal requirements and that all participants of the scheme were getting their fair share.

In 2011, shortly after Pérez Molina won the elections, Monzón also began to collect money for what would become a tradition later dubbed “La Cooperacha” or “The Collection.” Every year, on the eve of the president’s birthday, Monzón would visit the businessmen, politicians and officials who were benefiting from the corrupt administration and ask them for money to buy a gift for the president.

Monzón, who also gave the president an annual present, would later testify that the first gift he bought for Pérez Molina was a $25,000 Harley Davidson motorcycle. According to Monzón, the idea came after the “boss” saw a similar one on an official trip to Cancún.

Every year the gifts for the president had to be better than the last. The vice president’s private secretary eventually collected enough funds to give the president a million-dollar beach house, a $3.5 million helicopter and two boats.

Prosecutors told InSight Crime that the president knew he wanted a boat for his new beach house when he saw Sinibaldi on his boat. It was only after he’d gotten his yacht that Pérez Molina learned that the boat he saw was not Sinibaldi’s only one. In fact, the one that the president saw was the smallest boat in the Housing and Communications minister’s fleet.

The Minister’s Booty

In his recent testimony in court, José Luis Agüero, the owner of Asfaltos de Guatemala, said it was near the end of January 2012, just days after Pérez Molina and Baldetti took power, that he was summoned to the Infrastructure, Housing and Communications Ministry.

Newly appointed Minister and former Congressman Sinibaldi arrived more than an hour late. He was, according to those who interacted with him, an arrogant man. He took out a folder that summarized what in Guatemala is known as “leftover debt,” the total amount that the government owes to companies for contracts with previous administrations. In Agüero’s case, this debt was close to $7 million.

Sinibaldi raised his feet on his desk and told him that the only way to recover that money was through a “recognition” of 15 percent of the debt.

“Of course, I was scared. I was nervous. It took me by surprise, and I felt like I’d been pushed against the wall,” Agüero testified.

Sinibaldi repeated this meeting with other construction companies and businesses. The price was not the same for everyone. In some cases, the minister charged up to 35 percent of the total debt.

According to prosecutors, since the government did not have enough money to pay the debt, Sinibaldi issued government bonds, which serviced the debts and, of course, paid for his commission.

The minister also sold government public works contracts. The price, prosecutors say, was between 5 and 10 percent of the value of the contract.

Prosecutors highlighted the case of Otto and José Samayoa, who they referred to as “Los Brodercitos,” or “the brothers.” The two had become some of the biggest players in the construction industry thanks to public works projects they’d been doing since the 1990s.

José was also a former PP congressman. And during the presidential campaign, the brothers gave more than $3.6 million. Like Claro, they’d channeled the money through Sinibaldi’s companies.

During the Pérez Molina administration, those invoices continued to flow. At least three of the brothers’ companies bought services from Sinibaldi’s companies for an estimated $8 million. These services included the use of trucks and backhoes.

No services were rendered, but the return on the investment was substantial. Between 2012 and 2014, most of the more than 60 companies linked to “Los Brodercitos” were awarded contracts for millions of dollars most of them through Sinibaldi’s Infrastructure, Housing and Communications Ministry.

Some of the brothers’ companies even competed for state contracts amongst themselves to give these government tenders the appearance of legitimacy and legality.

In a scheme the Attorney General’s Office and CICIG would later dub “Construction and Corruption,” prosecutors say that Sinibaldi got at least $13 million in bribes from the brothers, Agüero and others, including the infamous Odebrecht Brazilian construction company. To hide the money, the minister, with the help of an old friend and business partner, Christian Ross, created at least 20 shell companies. Ross, who was also a PP congressman, received at least $67,000 from the 2011 Claro donation.

The Infrastructure, Housing and Communications Ministry manages one of the government’s largest budgets, so it was little surprise that Sinibaldi was one of the PP operatives who most benefited from the corruption. According to prosecutors, it was part of the plan. Pérez Molina and Baldetti were letting him get rich. Sinibaldi, they thought, was going to be the next president, and when he won, he was going to protect them and keep the corruption schemes going.

The End of the ‘Eternal Return’

When Vice President Baldetti got back from South Korea on April 17, 2015, she gave an emotional but brief press conference in which she said she had no information about the whereabouts of her private secretary, Monzón. Monzón had apparently followed his boss’ advice and gone on the run, and Baldetti spent the first few days defending him.

But in the days that followed, more information connecting Baldetti to La Línea emerged. Her strategy shifted, and she and Pérez Molina began to blame Monzón for the entire scheme.

“I cannot be held responsible for anyone but myself,” said Baldetti, agitated. “If I had wanted to stop something or intervene, I would have, but we let the investigation run its course.”

Baldetti’s plan backfired. Within days, she resigned and, in August of that year, she was arrested by authorities. Pérez Molina stepped down as president a month later. Shortly after, the attorney general issued a warrant for his arrest.

With his former bosses behind bars, Monzón turned himself in and became a cooperating witness.

Monzón’s sometimes detailed, sometimes salacious, but always interesting testimony lasted more than two months. Pérez Molina and Baldetti had an amorous relationship, he claimed at one point. And they had devised a “retirement chart of more than $2 million per year for 25 years,” based on what they made from La Línea. He painted a fairytale that included motorcycles, boats, helicopters and houses.

More importantly, his testimony detailed the schemes from the inside and allowed prosecutors to build a case against numerous corrupt officials, businessmen and others who also flipped. Martínez of Grupo Escorpión and the frontman Hernández became cooperating witnesses, providing documentation and hours of testimony about the PP’s corrupt practices.

It was an incredible scheme. Pérez Molina and Baldetti had laid the groundwork for the party’s own eternal return, applying all the tools of the state to ensure their structure could make the philosophical notion of an ever-repeating universe a reality. In the PP version, the pattern was to repeat once Sinibaldi took the presidency, but his schemes were also unraveling.

On June 28, 2017, Claro’s Central American operations manager Porras Zadik became the first businessman to admit he gave illicit campaign funds to the PP. The trail eventually led to the arrest of former ambassador to the United States, Ligorría, in Madrid in September 2017. López Bonilla was arrested in June 2016, and accused of having taken part in La Cooperacha. The former minister is also wanted for drug trafficking in the United States.

For his part, Sinibaldi resigned his candidacy just days after Baldetti arrived from South Korea, then attacked the government claiming that Baldetti sabotaged his campaign. “The principles of the Patriotic Party no longer exist, now there are petty interests. The misguided path that the country is on has led me to this conclusion,” he said during a press conference.

Sinibaldi’s name was not directly linked to La Línea, but it began to appear in various other cases, and the former minister, ex-senator, and nouveaux member of one of Guatemala’s most elite families simply left the country.

He was last seen a year later giving an interview on Skype, allegedly from a hotel in India. In the interview, Sinibaldi says he was learning about meditation and how to lead a quiet and peaceful life. He also said that he regularly met with members of another political party.

Two months later, Interpol issued an international arrest warrant against him for the Cooperacha case. Sinibaldi was also accused of money laundering and illicit association, related to his time as the Infrastructure, Housing and Communications Minister. Later, authorities linked him to the Construction and Corruption case. He remains on the run.

The Construction and Corruption case continued. On August 14, the Attorney General’s Office and the CICIG announced “phase 2” of the charges, outlining how Sinibaldi used foreign bank accounts to deposit bribes. The modus operandi was the same, they said: camouflage the work with invoices for services never rendered.

Monzón also left the country. Because of his cooperation with authorities, he was released in June 2017. He departed Guatemala soon after and has not returned.