They are known by supporters as “knights of steel” on their motorcycles, and as the most ardent defenders of Venezuela’s Bolivarian Revolution. Yet now they look more like criminal gangs with immense social control. Welcome to the world of the “colectivos.”

In 2002, President Hugo Chávez faced two attempts to unseat him from power: a military coup and a strike in the crucial oil sector. In the aftermath of these threats, he decided he needed parallel security structures that could act as a counterweight to the military and the ability to rapidly concentrate political shock troop against opposition demonstrators. His solution was the colectivos (collectives).

The term “colectivos” has its roots in the Venezuelan guerrilla groups of the 1960s. But it was appropriated by Chávez’s Bolivarian Revolution. In 2001, Chávez set up a new generation of political groups, the “Bolivarian Circles,” to build up grass-roots political support.

These Bolivarian Circles proved their loyalty and willingness to use violence during the April 2002 coup attempt. Video footage of April 11 shows anti-government protestors being engaged by armed men, later identified as members of Bolivarian Circles, who opened fire from the Llaguno Bridge in central Caracas. By the end of that day, 20 people lay dead and dozens more, both Chavistas and demonstrators, were wounded.

The military generals refused orders from Chavez to mobilize against the anti-government protests. Chávez eventually agreed to resign on condition that he and his family would be exiled in Cuba.3 Yet within 48 hours, Chávez was back in power, mostly thanks to General Rául Baduel, then the Commander of the 42nd Paratrooper Infantry Brigade, who rallied key sectors of the military. This was the moment that Chávez radicalized his revolution and determined to hang onto power at all costs.

Only three people were jailed after the violent events of April 11. One was Iván Simonovis, then head of the Metropolitan Police in Caracas. He was sentenced to 30 years in jail.

InSight Crime interviewed him in his house, where he has been under house arrest since 2014. For him, the violence of the Bolivarian Circles and the impunity surrounding the killings they committed that day are the precedent for the power and violence of the colectivos now.

“They said that the people shooting from the bridge were using force in self-defense against the police. How can you justify saying that a person firing on police is engaged in the legitimate use of force?” said Simonovis.

The term colectivo began to replace that of the Bolivarian Circles in the government’s public language after the coup. These pro-government enforcement groups in 2006 came under the umbrella of the government’s “communal councils,” through which they received state funding and resources, including weapons. They were granted legitimacy and real power in their areas of influence.

“The day jobs that many of these people [in the colectivos] have are actually as security for government officials. So that gives them direct access to government resources, but also to government weapons and the rest of it,” said Alejandro Velasco, an associate professor at New York University and author of “Barrio Rising,” a book on urban politics in Venezuela.

Inside the 23 de Enero Neighborhood

There is no place in Venezuela more emblematic of the Bolivarian Revolution and the colectivos than the 23 de Enero neighborhood of Caracas. Here is where many of the most infamous and powerful colectivos are based.

The Cuartel de La Montaña, Hugo Chávez’s final resting place, a fort oddly reminiscent of a European castle, looks down on the sprawling 23 de Enero neighborhood — a combination of improvised housing and shacks clustered around tall apartment blocks. The presidential palace, the Casa de Miraflores, is visible below.

Chavez’s image, those of the colectivos and the Bolivarian Revolution adorn the walls of the neighborhood.

Yet in recent years, its residents have begun to question not just the Chavista regime, but its local face, the colectivos. While a handful are still unarmed and focused on their original cultural and community roots, most have become armed enforcers who pledge allegiance to the revolution, funded in part through criminal activity.

InSight Crime entered the area with a respected community leader, our ticket to a neighborhood suspicious of outsiders. Many of the young men we passed had small leather bags strapped across their chests. Our guide told us many colectivo members carry their pistols that way — out of sight but easily accessible.

Every inch of the 23 de Enero is now controlled and monitored by the colectivos, residents told us. Colectivo roadblocks control and often tax the circulation of vehicles.

The colectivos have several streams of income, some legal, others definitely illegal. Of the legal streams, most come from the government, although some of colectivos have established businesses that turn a legal profit. The government income comes less and less via cash payments, but rather through concessions, like the distribution of food, which is now a very lucrative business.

“They [the colectivos] control the food [distribution] and have the whole neighborhood terrified. That’s the word: terrified,” said Claudia, a local resident, keeping her voice low.

Another resident, Rosa, was equally condemnatory.

“I don’t know where they get the food from, if they buy it, but then they sell it on the black market,” she said. “They talk about equality and the revolution and I don’t know what else, but then they sell food parcels at inflated prices.”

One of the leaders of the historic Tupamaros colectivo, Lisandro Pérez, better known by his alias “Mao,” compared food trafficking to drug trafficking in terms of earnings.

“A lot of those who sold drugs are now trafficking food. It’s less risky and more profitable,” he told InSight Crime.

The same goes for sales of medicine, which is now always in short supply and can command extortionate prices from the desperate.

As far as illegal earnings are concerned, InSight Crime found evidence of involvement in the sale and distribution of drugs, extortion and illegal gambling.

“More [common] than anything here is the sale of drugs and they go around with weapons at whatever time they like,” said Rosa, serving a coffee inside her house.

“The sale of drugs here is as common as the sale of Coca-Cola. The colectivos control the drug distribution — those that have the power to do so,” admitted a colectivo leader in 23 de Enero who wanted himself identified only as “Galeano Marcos.”

Interviews with residents and colectivo leaders also revealed that the colectivos are running clandestine casinos in the 23 de Enero.

“The colectivos manage [the casinos]. And they escort the people who come to bet, and afterwards they escort them out,” said local resident Claudia.

Mao confirmed the existence of the casinos as the latest criminal enterprise to emerge in the 23 de Enero. He also admitted they were managed by the colectivos, although he insisted he is against them on an ethical level.

“I can’t deny people the right to enjoy themselves, but I can’t say I approve of the casinos because they generate a commercial culture, the idea that being a man is about having more to assert dominance,” he said.

Mao is scornful of some of the newer colectivos. His Tupamaros predate Chávez, as they were formed in 1979. However, their power grew exponentially under Chávez.

“The term colectivo is being used all over the place … but I think that there are colectivos that unfortunately have to disappear,” Mao stated.

Marcos Galeano went even further.

“Each colectivo has a boss and commander, and they all want to be colectivos because they want weapons. Everyone here wants to have more weapons than the others. Each leader is in charge of his territory and does whatever he likes there. Here they say they’re democrats, but you do what the boss tells you,” he said.

La Piedrita

The messianic mythology of one of the most notorious colectivos of the 23 de Enero is perfectly illustrated in this picture. Jesus, wearing his crown of thorns wielding a Kalashnikov, alongside the Virgin, cradling the baby Jesus and another AK-47.

This is the public face of La Piedrita (Little Stone).

The colectivo La Piedrita was born before Chavismo. Its founders Valentín Santana and Carlos Ramírez created the group in September 1985 in an effort to reverse the violence dominating parts of the 23 de Enero neighborhood. A number of Santana’s siblings and extended family members belong to the colectivo, which is defined by strong Marxist-Leninist principles.

La Piedrita runs a local radio station, and provided facilities for the Cuban doctors, now long gone, who once came to serve the community. The colectivo also owns a small urban farm that breeds chickens and grows vegetables, which are sold locally prices. Plans for a bakery are in the works.

But the colectivo is better known for its violent acts and reputation, and has come to represent the aggression associated with pro-government groups.

Members of La Piedrita have attacked opposition protestors and media with tear gas, accusing them of blocking the revolutionary process. Santana, who has military experience that he has used to instill a sense of discipline and a strong vertical structure within the group, has stated that La Piedrita is willing to defend the Bolivarian Revolution “at all costs.”

To date, Santana has three arrest warrants in his name, two of them for homicide. Despite this, he frequently appears in public and has been interviewed by the international media. In February this year, Satana posted a video on his Twitter feed, showing himself embracing top government officials, including General Fabio Zavarse Pabón, the commander of all Bolivarian National Guard (Guardia Nacional Bolivariana – GNB) and army troops in the Capital District who was recently sanctioned by the United States for the repression of demonstrations.

Assumption of State Powers

The power of the colectivos is not restricted to running rackets in their areas of influence. Since the Metropolitan Police was dismantled by Chávez in 2011, the regime abdicated security in the 23 de Enero, as well as some other parts of the capital, to the colectivos. State security forces are obliged to coordinate with them to enter these areas. Manuel Mir, a community leader in the 23 de Enero, told InSight Crime that the colectivos have turned the neighborhood into a “state within a state.”

Some of the colectivos work alongside the security forces, often doing their dirty work for them.

Colectivos like “Tres Raíces” and “Frente 5 de Marzo” are well known for their close links to elements of the security forces.

Tres Raíces is one of the better armed colectivos, and several of its members are serving in either the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (Servicio Bolivariano de Inteligencia Nacional – Sebin), Libertador’s Municipal Police Force (Policía del Municipio Libertador – PoliCaracas), the General Directorate of Military Counterintelligence (Dirección General de Contrainteligencia Militar – DGCIM) or the Special Action Force of the Bolivarian National Police (Fuerza de Acciones Especiales – FAES).

Even though members of Tres Raíces have been linked to kidnappings and murders, high-level contacts in the security forces have meant they have not been prosecuted for these crimes.

The Frente 5 de Marzo colectivo was founded by a former policeman, José Miguel Odremán, who was killed in a 2014 security force operation. His colectivo was under investigation for seven murders, as well as robbery and extortion. It also set up a bodyguard service, the Venezuelan Bolivarian Association of Bodyguards (Asociación Bolivariana de Escoltas de Venezuela), essentially acting as hired guns.

There have also been accusations that colectivos have been involved in the controversial Operations to Liberate the People (Operativo de Liberación del Pueblo – OLP). These are anti-crime offensives launched by President Nicolás Maduro to try to bring down rampant crime rates. They have been marked by high numbers of killings and accusations that there is a “shoot first, ask questions later” mentality.

The OLPs have failed in their primary objective of reducing crime, but have fed record murder rates, amid accusations that government forces have engaged in extrajudicial executions. Survivors and families of their victims say that participants in the OLPs shoot to kill.

“The OLPs have killed innocent people, because they break into houses and kill people without asking who they are,” said local resident Claudia.

Witnesses say the involvement of colectivos in the OLPs vary. Often they work with the state security forces in 23 de Enero, where they have much more local knowledge.

“The OLPs come with all the different security bodies and the colectivos always hood themselves and mix in with them,” said Claudia.

Another 23 de Enero resident told InSight Crime that the involvement of the pro-government groups is even more sinister.

“It’s the colectivos that do the executions,” she said.

The colectivos still perform their traditional role as political shock troops and were deployed against the wave of protests that took place in 2017, using tear gas canisters and even firing pistols to break up opposition protests.

Luis Cedeño, who runs the non-governmental organization Paz Activa, which studies criminality in Venezuela, now sees the colectivos as a pool of mercenary labor for the government, and increasingly for organized crime.

“They are paid to generate violence … paid by specific interests that seek to create chaos,” he said in a video produced by his organization.

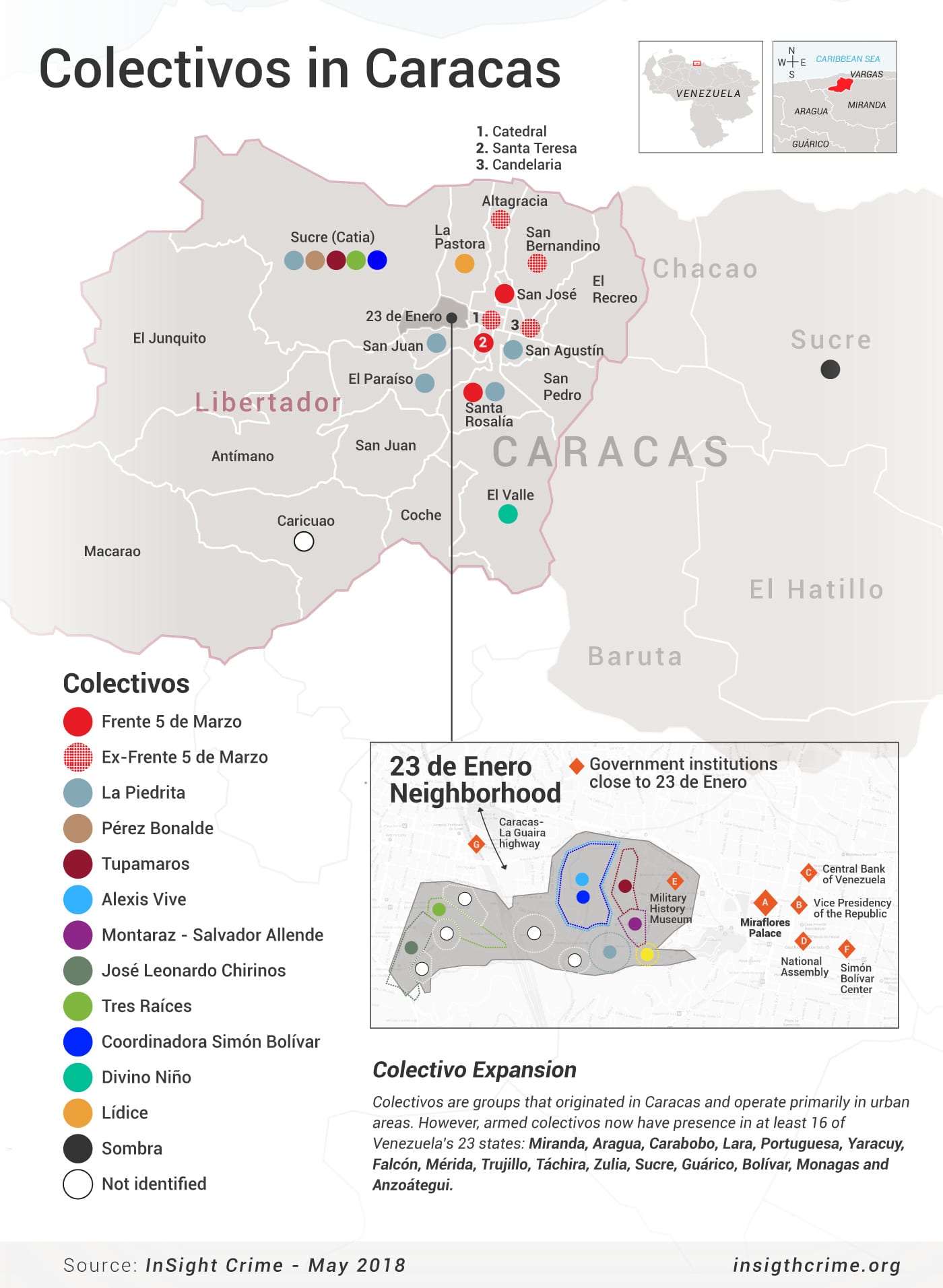

Research by InSight Crime points to the presence of 46 colectivos in the 23 de Enero neighborhood, ranging from “traditional” to “emerging” models, which we have referred to in our map as “hybrids.” Some of these groups are small with no known identity, but we have mapped the ones we think are the most significant.

Many of the colectivos members we spoke to still refer to Chávez with reverence. For the most part, they only have scorn for Maduro.

“The death of Comandante Chávez brought us to a crossroads. It’s not the same, the leadership of Chávez compared to those who have taken over,” said colectivo leader Marcos.

It is clear that government control of the colectivos has weakened, if not evaporated in many cases. This is in part due to the current political chaos and economic meltdown, which the colectivos do not see as a weakness of the Bolivarian Revolution. Rather, they attribute the situation to Maduro’s betrayal of revolutionary principles. The other reason is that the government is broke and has cut back funding on all fronts, including funding destined for the colectivos. This has forced the colectivos to become more financially self-sufficient, which in many cases has meant engaging in criminal activity.

There is also a connection between some of the colectivos and Colombian rebel groups, a relationship initially fostered by Chávez but now out of Maduro’s hands. Some colectivos have received training at the hands of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC). On a visit to 23 de Enero we found a bust of the legendary FARC founder and leader, Pedro Antonio Marín, alias “Manuel Marulanda”.

Evidence from FARC dissident and security force sources in Colombia suggests that relationships are being developed with Venezuelan groups like the colectivos, more in the interests of illegal business than ideological affinity.

If the opposition wins the upcoming presidential election and the National Assembly is reinstated as Venezuela’s primary legislative body, it is likely that the colectivos will find themselves under enormous pressure to disarm and disband.

Therefore, the survival of the colectivos depends on the survival of the regime. Should the ruling party fall, what is left of the support and tolerance of the colectivos will also crumble, giving them one of two choices: disband, or transform into purely criminal entities.