In January 2018, US authorities began following a Bulgarian biochemist named Antov Petrov Kulkin who they believed was running a small carfentanil/fentanyl laboratory in Mexico.

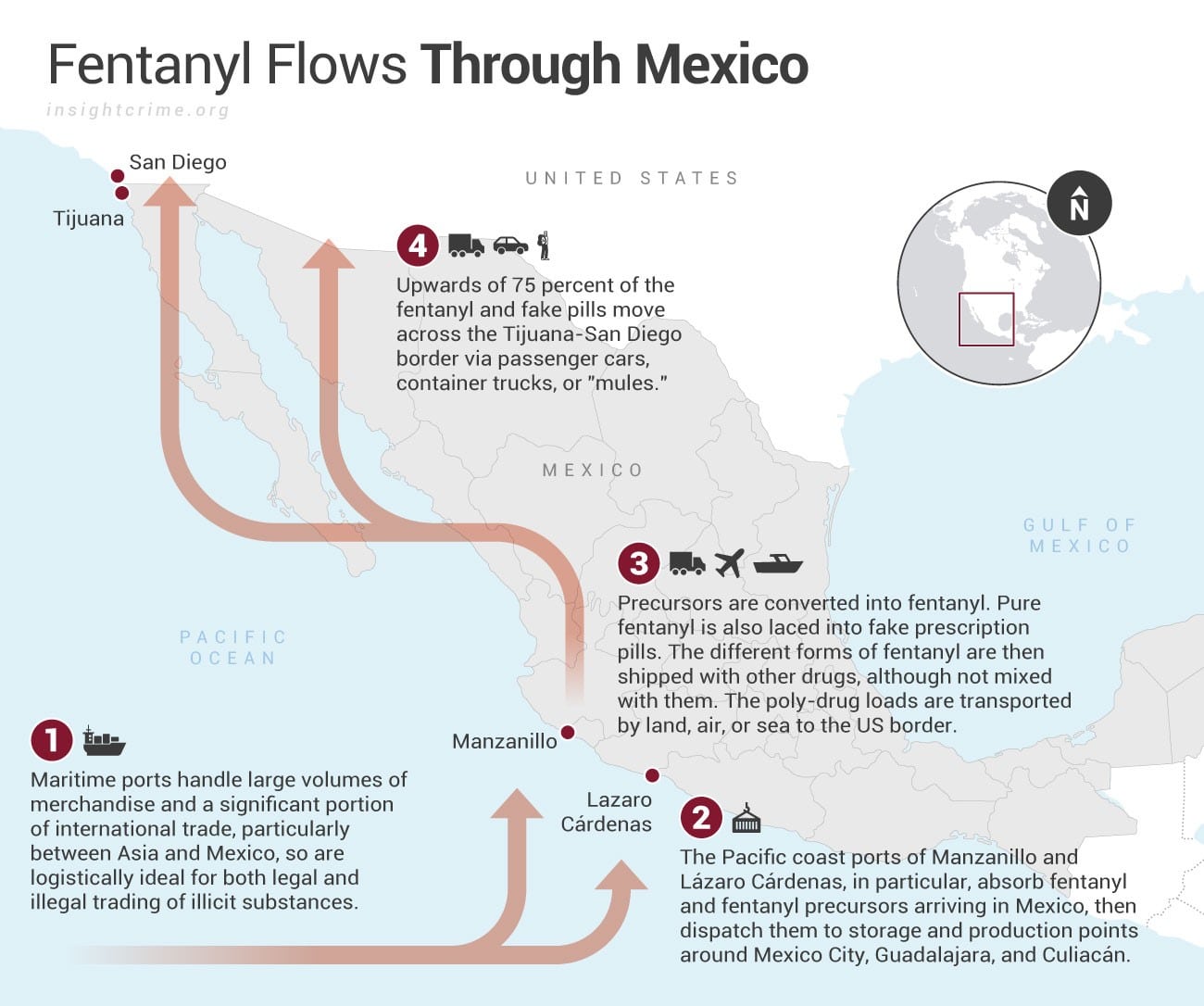

Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid, has proliferated in recent years in the United States, and close to 30,000 people died by overdosing on the drug in 2017. Its potency could be a gamechanger for the illicit drug industry. Small amounts mean less risk in the production and transport process but still significant profits. Production of fentanyl is also relatively simple and cheap, opening the door for smaller groups to enter the trade using small spaces and moving small quantities over the dark web.

*This article is part of a series on the growing demand for fentanyl and its deadly consequences done with the support of the Mexico Institute at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. See the rest of the series here.

To be sure, interviews and testimony from federal government officials during our investigation into fentanyl-trafficking networks indicate that the trafficking of fentanyl via small quantities through the traditional mail system could represent “the future of the drug problem in America,” according to the US Helsinki Commission.

Other officials we consulted also told InSight Crime that this could be a watershed moment where the hierarchical drug trafficking organizations that have dominated the drug trade may no longer have a monopoly on the supply of illicit drugs.

In some respects, fentanyl is like the computer microchip market. There is the potential of producers to create smaller and smaller analogs, reducing the need to use large criminal infrastructures to ship the product to its consumers.

This is already happening: Carfentanil, a fentanyl analog, is an estimated 100 times more potent than fentanyl, and has been detected in places as disparate as San Diego and New Hampshire, US counterdrug officials in both areas told InSight Crime. Reports of carfentanil have also risen from zero in 2015, to over 6,000 incident reports in 2017.

SEE ALSO: Coverage of Fentanyl

Enter Kulkin. Working undercover, multiple US counterdrug agents in New England, California, Santo Domingo, and Tijuana began interacting with his network. Eventually, they conducted confidential undercover source meetings in Santo Domingo and Tijuana, and undercover pill purchases in California.

The investigation led to seizures in California and uncovered connections between Kulkin’s network and the Sinaloa Cartel, including strains of other Sinaloa-related distribution networks operating in the United States. In August 2018, US counterdrug agents, working with Mexican authorities, developed a strategy to arrest Kulkin in Mexico, as well as other parts of his distribution network in Massachusetts.

And in September 2018, after locating his apartment in Mexicali, Mexican authorities arrested Ivan Arredondo-Ramirez who tried to bribe his way to freedom before being taken into custody. Arredondo-Ramirez later admitted to being Kulkin’s boss.

Soon after, authorities arrested Kulkin and found the carfentanil/fentanyl laboratory. There they seized as much as 20,000 counterfeit pills and a pill press, among other items, which Arredondo-Ramirez and Kulkin allegedly used to produce counterfeit pills, which they sold in the US.

This counterfeit pill form appears to be the current vehicle of choice for Mexican-based traffickers. Of nine fentanyl seizures in August 2018 along the San Diego border, for instance, five were in pill form, significantly more than in previous months. Overall, US authorities along the San Diego-Tijuana border say that counterfeit pills represented more than 30 percent of the total fentanyl seizures in FY2018, up from five percent in FY2017.

They believe this upward trend will continue, since many fentanyl users are not purposely seeking the dangerous drug, and it generates such high returns. According to the Fentanyl Working Group, a collection of law enforcement agencies working out of the San Diego area, one kilogram of fentanyl, which costs $32,000, can make one million counterfeit pills with a street value of $20 million.[1]

The criminal market for counterfeit drugs is already huge and has relatively low barriers of entry. The United Nations estimates that as much as one-third of the world’s prescription drugs are counterfeit. In the case of Mexico, initial indications were that smaller criminal groups operating along the US-Mexico border were establishing “pharma cartels” and peddling their drugs over the internet. The larger criminal groups were taxing them for their operations, rather than exerting control at that time. That may change, especially as the larger criminal groups lose hegemony in other criminal markets and look to compete in new markets like fentanyl.