Authorities in southwest Colombia’s Valle del Cauca province are bracing themselves for another violent realignment of underworld forces following the capture of the region’s most powerful criminal leader, ‘Diego Rastrojo.’

Venezuelan police, working with Colombian intelligence officers, seized Rastrojo, whose real name is Diego Perez Henao, on June 3 in the Barinas province in Central Venezuela. His group, called the Rastrojos after their leader, holds sway over large areas of drug production and trafficking corridors from the northern part of this fertile province stretching south to the Ecuadorean border, and includes as many as 1,000 armed men.

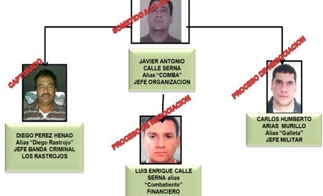

However, rivals from a group known as the Urabeños appear ready to fill the void left by Rastrojo and his former partners, the Calle Serna brothers, known as “Los Comba,” who shared the leadership of the Rastrojos until recently. Javier Calle Serna turned himself over to US authorities in May; in April, Ecuadorean authorities captured Juan Carlos Calle Serna, alias “Armando,” in that country. Luis Enrique Calle Serna, a third brother, is still at large but thought to be negotiating his own handover to the US.

There is no clear successor to the Rastrojos’ throne, though several names have been mentioned, which seem to share a gastronomic theme: “Galleta” (Cookie), “Chorizo” (Sausage), “Pollo Bobo” (Stupid Chicken), and “Avestruz” (Ostrich) all appear on the list of possible leaders of the group. Rastrojo’s brother, alias “Burro,” may also be vying for power, according to El Pais.

Matters are complicated by the two-pronged structure of the organization, and by recent infighting. Whereas the Combas emerged from the ranks of the urban assassination rings in provincial capital Cali, Diego Rastrojo hailed from the more rural northern part of the Valle. The two factions split in recent months due to Javier Calle Serna’s efforts to negotiate his handover to US authorities, and it’s not clear which part of the organization was loyal to the Combas and which part was loyal to Diego Rastrojo.

The resulting turmoil has opened the door to the Urabeños, who may already be in Valle del Cauca. Reports are circulating of an alliance between the group and former members of a drug running faction run by Diego Montoya, known as the Machos.

Montoya created the Machos in the early 2000s to fight his rival Wilber Varela, who founded the Rastrojos. Montoya was captured and extradited to the US in 2007, but his Machos survived. The Rastrojos killed Varela in 2008, in his Venezuelan hideout, and set up their own operations.

The Machos are currently run by Hector Urdinola Alvarez, alias “Chicho” or “El Zarco,” a nephew of Ivan Urdinola, former leader of the infamous Urdinola clan that controlled a huge part of the Norte del Valle Cartel in the 1990s. The Machos operate in the municipalities of Zarzal, La Victoria and Roldanillo in the northeastern part of the province. They do not have the troop strength or capacity of their rivals the Rastrojos, but they once infiltrated the army to the highest levels and may seek to regain that advantage in the battles to come.

There are also unconfirmed reports of the re-emergence of two key players from the Valle del Cauca drug trafficking groups. As InSight Crime reported last year, Martin Fernando Varon, alias “Martin Bala,” a key operator in Cali underworld circles, was thought to be behind a number of assassinations in Cali of alleged associates of the Comba brother associates.

Add to this the arrival of Victor Patiño, who oscillated between the Cali Cartel and the Norte del Valle Cartel. Patiño allegedly entered Colombia via Panama shortly after finishing a 10-year prison term in the US, seeking new alliances to reclaim lost properties and avenge the death of some 30 family members at the hands of the Comba brothers, among others, following his extradition and alleged cooperation with US authorities.

Together, the Urabeños, Machos, Bala and Patiño would make a formidable group, especially during this uncertain period of transition in the northern part of the province. However, aside from the capture of six alleged members, evidence of the Urabeños’ presence is scant. For his part, Patiño has not been seen, and some authorities say his presence is a myth designed to inspire fear.

While violence is expected to rise in key Rastrojos areas such as Tulua and possibly Dovio, where the group controls the lucrative production point known as the Cañon de Garrapatas, this may be due to infighting amongst mid-level commanders who seek to gain control of this strip. The valuable territory offers production and processing of drugs, and access to numerous coastal launch points for narcotics shipments.

The precarious state of the Rastrojos, which, until a month ago, was considered one of Colombia’s most powerful drug trafficking organizations, is a testament to the rapidly mutating and complex nature of these organizations. While the government has denominated them “criminal bands,” or BACRIM, they seem to be more mercenary than paramilitary, more ad hoc than structured.

At the BACRIMs’ core remain demobilized fighters from the now defunct right-wing paramilitary organizations that fought the guerrillas at the behest of the state, wealthy landowners and businessmen. But each successive mutation leaves them a little further from their origins. New recruits lack the training and discipline of their successors, and mid-level commanders seem open to working for the highest bidder, or simply content to go it on their own.

The fluidity of the situation was illustrated in 2010 in the oil-refining city of Barrancabermeja, where Rastrojos members switched allegiances to the Urabeños virtually overnight over a lag of more than five months in their paychecks, because the cash destined for the payments had been seized in the Pacific port of Buenaventura.

The same could happen again in Valle del Cauca, authorities say. Most Rastrojos soldiers receive between 500,000 and 800,000 pesos per month (around $280-$450), less than half of what they once made. And cash flow can be a problem, especially since the Rastrojos appear to have a centralized accounting system, which could cause bureaucratic delays in payments, thus opening soldiers up to switching teams.

Perhaps equally important is the Urabeños’ reputation as a ruthless but disciplined fighting force. The Urabeños and the Rastrojos have benefited from their superior tactical and strategic control of territory, but the Urabeños may now be the more experienced of the two. What’s more, the rank and file of the BACRIMs seem to respond more to the winds of change than to any commander’s voice.